Related Research Articles

Pasteurization or pasteurisation is a process of food preservation in which packaged and non-packaged foods are treated with mild heat, usually to less than 100 °C (212 °F), to eliminate pathogens and extend shelf life. The process is intended to destroy or deactivate microorganisms and enzymes that contribute to food spoilage or risk of disease, including vegetative bacteria, but most bacterial spores survive the process.

An endospore is a dormant, tough, and non-reproductive structure produced by some bacteria in the phylum Bacillota. The name "endospore" is suggestive of a spore or seed-like form, but it is not a true spore. It is a stripped-down, dormant form to which the bacterium can reduce itself. Endospore formation is usually triggered by a lack of nutrients, and usually occurs in gram-positive bacteria. In endospore formation, the bacterium divides within its cell wall, and one side then engulfs the other. Endospores enable bacteria to lie dormant for extended periods, even centuries. There are many reports of spores remaining viable over 10,000 years, and revival of spores millions of years old has been claimed. There is one report of viable spores of Bacillus marismortui in salt crystals approximately 250 million years old. When the environment becomes more favorable, the endospore can reactivate itself into a vegetative state. Most types of bacteria cannot change to the endospore form. Examples of bacterial species that can form endospores include Bacillus cereus, Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus thuringiensis, Clostridium botulinum, and Clostridium tetani. Endospore formation is not found among Archaea.

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, central heating, boiler-based power generation, cooking, and sanitation.

An autoclave is a machine used to carry out industrial and scientific processes requiring elevated temperature and pressure in relation to ambient pressure and/or temperature. Autoclaves are used before surgical procedures to perform sterilization and in the chemical industry to cure coatings and vulcanize rubber and for hydrothermal synthesis. Industrial autoclaves are used in industrial applications, especially in the manufacturing of composites.

Sterilization refers to any process that removes, kills, or deactivates all forms of life and other biological agents such as prions present in or on a specific surface, object, or fluid. Sterilization can be achieved through various means, including heat, chemicals, irradiation, high pressure, and filtration. Sterilization is distinct from disinfection, sanitization, and pasteurization, in that those methods reduce rather than eliminate all forms of life and biological agents present. After sterilization, an object is referred to as being sterile or aseptic.

Bacillus subtilis, known also as the hay bacillus or grass bacillus, is a Gram-positive, catalase-positive bacterium, found in soil and the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants, humans and marine sponges. As a member of the genus Bacillus, B. subtilis is rod-shaped, and can form a tough, protective endospore, allowing it to tolerate extreme environmental conditions. B. subtilis has historically been classified as an obligate aerobe, though evidence exists that it is a facultative anaerobe. B. subtilis is considered the best studied Gram-positive bacterium and a model organism to study bacterial chromosome replication and cell differentiation. It is one of the bacterial champions in secreted enzyme production and used on an industrial scale by biotechnology companies.

An antimicrobial is an agent that kills microorganisms (microbicide) or stops their growth. Antimicrobial medicines can be grouped according to the microorganisms they act primarily against. For example, antibiotics are used against bacteria, and antifungals are used against fungi. They can also be classified according to their function. The use of antimicrobial medicines to treat infection is known as antimicrobial chemotherapy, while the use of antimicrobial medicines to prevent infection is known as antimicrobial prophylaxis.

Coliform bacteria are defined as either motile or non-motile Gram-negative non-spore forming Bacilli that possess β-galactosidase to produce acids and gases under their optimal growth temperature of 35-37°C. They can be aerobes or facultative aerobes, and are a commonly used indicator of low sanitary quality of foods, milk, and water. Coliforms can be found in the aquatic environment, in soil and on vegetation; they are universally present in large numbers in the feces of warm-blooded animals as they are known to inhabit the gastrointestinal system. While coliform bacteria are not normally causes of serious illness, they are easy to culture, and their presence is used to infer that other pathogenic organisms of fecal origin may be present in a sample, or that said sample is not safe to consume. Such pathogens include disease-causing bacteria, viruses, or protozoa and many multicellular parasites.

A conidium, sometimes termed an asexual chlamydospore or chlamydoconidium, is an asexual, non-motile spore of a fungus. The word conidium comes from the Ancient Greek word for dust, κόνις (kónis). They are also called mitospores due to the way they are generated through the cellular process of mitosis. They are produced exogenously. The two new haploid cells are genetically identical to the haploid parent, and can develop into new organisms if conditions are favorable, and serve in biological dispersal.

Infection prevention and control is the discipline concerned with preventing healthcare-associated infections; a practical rather than academic sub-discipline of epidemiology. In Northern Europe, infection prevention and control is expanded from healthcare into a component in public health, known as "infection protection". It is an essential part of the infrastructure of health care. Infection control and hospital epidemiology are akin to public health practice, practiced within the confines of a particular health-care delivery system rather than directed at society as a whole.

Geobacillus stearothermophilus is a rod-shaped, Gram-positive bacterium and a member of the phylum Bacillota. The bacterium is a thermophile and is widely distributed in soil, hot springs, ocean sediment, and is a cause of spoilage in food products. It will grow within a temperature range of 30 to 75 °C. Some strains are capable of oxidizing carbon monoxide aerobically. It is commonly used as a challenge organism for sterilization validation studies and periodic check of sterilization cycles. The biological indicator contains spores of the organism on filter paper inside a vial. After sterilizing, the cap is closed, an ampule of growth medium inside of the vial is crushed and the whole vial is incubated. A color and/or turbidity change indicates the results of the sterilization process; no change indicates that the sterilization conditions were achieved, otherwise the growth of the spores indicates that the sterilization process has not been met. Recently a fluorescent-tagged strain, Rapid Readout(tm), is being used for verifying sterilization, since the visible blue fluorescence appears in about one-tenth the time needed for pH-indicator color change, and an inexpensive light sensor can detect the growing colonies.

Aseptic processing is a processing technique wherein commercially thermally sterilized liquid products are packaged into previously sterilized containers under sterile conditions to produce shelf-stable products that do not need refrigeration. Aseptic processing has almost completely replaced in-container sterilization of liquid foods, including milk, fruit juices and concentrates, cream, yogurt, salad dressing, liquid egg, and ice cream mix. There has been an increasing popularity for foods that contain small discrete particles, such as cottage cheese, baby foods, tomato products, fruit and vegetables, soups, and rice desserts.

Soil steam sterilization is a farming technique that sterilizes soil with steam in open fields or greenhouses. Pests of plant cultures such as weeds, bacteria, fungi and viruses are killed through induced hot steam which causes vital cellular proteins to unfold. Biologically, the method is considered a partial disinfection. Important heat-resistant, spore-forming bacteria can survive and revitalize the soil after cooling down. Soil fatigue can be cured through the release of nutritive substances blocked within the soil. Steaming leads to a better starting position, quicker growth and strengthened resistance against plant disease and pests. Today, the application of hot steam is considered the best and most effective way to disinfect sick soil, potting soil and compost. It is being used as an alternative to bromomethane, whose production and use was curtailed by the Montreal Protocol. "Steam effectively kills pathogens by heating the soil to levels that cause protein coagulation or enzyme inactivation."

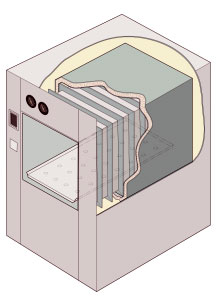

Hot air ovens are electrical devices which use dry heat to sterilize. They were originally developed by Louis Pasteur. Generally, they use a thermostat to control the temperature. Their double walled insulation keeps the heat in and conserves energy, the inner layer being a poor conductor and outer layer being metallic. There is also an air filled space in between to aid insulation. An air circulating fan helps in uniform distribution of the heat. These are fitted with the adjustable wire mesh plated trays or aluminium trays and may have an on/off rocker switch, as well as indicators and controls for temperature and holding time. The capacities of these ovens vary. Power supply needs vary from country to country, depending on the voltage and frequency (hertz) used. Temperature sensitive tapes or biological indicators using bacterial spores can be used as controls, to test for the efficacy of the device during use.

Tyndallization is a process from the nineteenth century for sterilizing substances, usually food, named after its inventor John Tyndall, that can be used to kill heat-resistant endospores. Although now considered dated, it is still occasionally used.

Steam is a substance containing water in the gas phase, and sometimes also an aerosol of liquid water droplets, or air. This may occur due to evaporation or due to boiling, where heat is applied until water reaches the enthalpy of vaporization. Steam that is saturated or superheated is invisible; however, wet steam, a visible mist or aerosol of water droplets, is often referred to as "steam".

A Biological Indicator Evaluation Resistometer (BIER) vessel is a piece of equipment used to determine the time taken to reduce survival of a given organism by 90%. The name derives from how the equipment is used.

Pascalization, bridgmanization, high pressure processing (HPP) or high hydrostatic pressure (HHP) processing is a method of preserving and sterilizing food, in which a product is processed under very high pressure, leading to the inactivation of certain microorganisms and enzymes in the food. HPP has a limited effect on covalent bonds within the food product, thus maintaining both the sensory and nutritional aspects of the product. The technique was named after Blaise Pascal, a 17th century French scientist whose work included detailing the effects of pressure on fluids. During pascalization, more than 50,000 pounds per square inch may be applied for approximately fifteen minutes, leading to the inactivation of yeast, mold, and bacteria. Pascalization is also known as bridgmanization, named for physicist Percy Williams Bridgman.

Endospore staining is a technique used in bacteriology to identify the presence of endospores in a bacterial sample. Within bacteria, endospores are protective structures used to survive extreme conditions, including high temperatures making them highly resistant to chemicals. Endospores contain little or no ATP which indicates how dormant they can be. Endospores contain a tough outer coating made up of keratin which protects them from nucleic DNA as well as other adaptations. Endospores are able to regerminate into vegetative cells, which provides a protective nature that makes them difficult to stain using normal techniques such as simple staining and gram staining. Special techniques for endospore staining include the Schaeffer–Fulton stain and the Moeller stain.

Microbes can be damaged or killed by elements of their physical environment such as temperature, radiation, or exposure to chemicals; these effects can be exploited in efforts to control pathogens, often for the purpose of food safety.

References

- 1 2 Prof. C P Baveja (1940), "Textbook of Microbiology", Nature, 146 (3692): 149, Bibcode:1940Natur.146..149H, doi: 10.1038/146149a0 , ISBN 81-7855-266-3, S2CID 37953413

- 1 2 Ananthanarayan; Panikar (1940), "Textbook of Microbiology", Nature, 146 (3692): 149, Bibcode:1940Natur.146..149H, doi: 10.1038/146149a0 , ISBN 81-250-2808-0, S2CID 37953413

- 1 2 3 Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion (DHQP) (2008). "Flash Sterilization". National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)