Steuben County is a county in the northeast corner of the U.S. state of Indiana. As of the 2020 United States Census the county population was 34,435. The county seat is Angola. Steuben County comprises the Angola, IN Micropolitan Statistical Area.

The Potawatomi, also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie, are a Native American people of the Great Plains, upper Mississippi River, and western Great Lakes region. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a member of the Algonquian family. The Potawatomi call themselves Neshnabé, a cognate of the word Anishinaabe. The Potawatomi are part of a long-term alliance, called the Council of Three Fires, with the Ojibwe and Odawa (Ottawa). In the Council of Three Fires, the Potawatomi are considered the "youngest brother". Their people are referred to in this context as Bodéwadmi, a name that means "keepers of the fire" and refers to the council fire of three peoples.

The siege of Fort Wayne took place from September 5 – September 12, 1812, during the War of 1812. The stand-off occurred in the modern city of Fort Wayne, Indiana between the U.S. military garrison at Fort Wayne and a combined force of Potawatomi and Miami forces. The conflict began when warriors under the Potawatomi chiefs, Winamac and Five Medals killed two members of the U.S. garrison. Over the next several days, the Potawatomi burned the buildings and crops of the fort's adjacent village, and launched assaults from outside the fort. Winamac withdrew on 12 September, ahead of reinforcements led by Major General William Henry Harrison.

The Treaty of Mississinewas or the Treaty of Mississinewa also called Treaty of the Wabash is an 1826 treaty between the United States and the Miami and Potawatomi Tribes regarding purchase of Indian lands in Indiana and Michigan. The signing was held at the mouth of the Mississinewa River on the Wabash, hence the name.

Citizen Potawatomi Nation is a federally recognized tribe of Potawatomi people located in Oklahoma. The Potawatomi are traditionally an Algonquian-speaking Eastern Woodlands tribe. They have 29,155 enrolled tribal members, of whom 10,312 live in the state of Oklahoma.

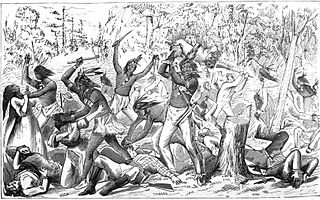

The Indian Creek Massacre occurred on May 21, 1832 with the attack by a party of Native Americans on a group of United States settlers in LaSalle County, Illinois following a dispute about a settler-constructed dam that prevented fish from reaching a nearby Potawatomi village. The incident coincided with the Black Hawk War, but it was not a direct action of the Sauk leader Black Hawk and conflict with the United States. The removal of the dam was asked, was rejected by the settlers and between 40 and 80 Potawatomis and three Sauks attacked and killed fifteen settlers, including women and children. Two young women kidnapped by the Indians were ransomed and released unharmed about two weeks later.

Leopold Pokagon was a Potawatomi Wkema (leader). Taking over from Topinbee, who became the head of the Potawatomi of the Saint Joseph River Valley in Michigan, a band that later took his name.

Winamac was the name of a number of Potawatomi leaders and warriors beginning in the late 17th century. The name derives from a man named Wilamet, a Native American from an eastern tribe who in 1681 was appointed to serve as a liaison between New France and the natives of the Lake Michigan region. Wilamet was adopted by the Potawatomis, and his name, which meant "Catfish" in his native Eastern Algonquian language, was soon transformed into "Winamac", which means the same thing in the Potawatomi language. The Potawatomi version of the name has been spelled in a variety of ways, including Winnemac, Winamek, and Winnemeg.

Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians are a federally recognized Potawatomi-speaking tribe based in southwestern Michigan and northeastern Indiana. Tribal government functions are located in Dowagiac, Michigan. They occupy reservation lands in a total of ten counties in the area.

The Potawatomi Trail of Death was the forced removal by militia in 1838 of about 859 members of the Potawatomi nation from Indiana to reservation lands in what is now eastern Kansas.

The Yellow River is a 62.3-mile-long (100.3 km) tributary of the Kankakee River in the Central Corn Belt Plains ecoregion, located in northern Indiana in the United States. Via the Kankakee and Illinois rivers, it is part of the watershed of the Mississippi River, draining an area of 427 square miles (1,110 km2).

Shabbona or Shab-eh-nay, sometimes referred to as Shabonee and Shaubena, was an Ottawa tribe member who became a chief within the Potawatomi tribe in Illinois during the 19th century.

The Attack at Ament's Cabin was an event during the Black Hawk War that occurred on 17 or June 18, 1832. The cabin site, in present-day Bureau County, Illinois, was settled by John L. Ament and his brother in 1829, although Ament's brother was quickly bought out by Elijah Phillips. After the 1832 Black Hawk War broke out, Ament and Phillips evacuated the site but later returned to collect belongings. On the morning of 17 or 18 June, the men were attacked by a band of Potawatomi, led by Mike Girty, probably those responsible for the Indian Creek massacre in May. Phillips was killed and the other men took shelter in Ament's cabin. Soldiers from Hennepin arrived after the attack and found Phillips' badly tomahawked body where he had fallen. They set off in a short pursuit of the attackers but eventually returned to Hennepin, Illinois with Phillips' remains.

Carey Mission was established in December 1822 by Baptist missionary Isaac McCoy among the Potawatomi tribe of American Indians on the St. Joseph River near Niles, Michigan, United States. It was named for English Baptist missionary William Carey. Its official nature and reputation made it a headquarters for settlers and an edge of the American frontier.

Indian removals in Indiana followed a series of the land cession treaties made between 1795 and 1846 that led to the removal of most of the native tribes from Indiana. Some of the removals occurred prior to 1830, but most took place between 1830 and 1846. The Lenape (Delaware), Piankashaw, Kickapoo, Wea, and Shawnee were removed in the 1820s and 1830s, but the Potawatomi and Miami removals in the 1830s and 1840s were more gradual and incomplete, and not all of Indiana's Native Americans voluntarily left the state. The most well-known resistance effort in Indiana was the forced removal of Chief Menominee and his Yellow River band of Potawatomi in what became known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death in 1838, in which 859 Potawatomi were removed to Kansas and at least forty died on the journey west. The Miami were the last to be removed from Indiana, but tribal leaders delayed the process until 1846. Many of the Miami were permitted to remain on land allotments guaranteed to them under the Treaty of St. Mary's (1818) and subsequent treaties.

Tetinchoua was a Miami chief who had lived during the 17th century. Nicolas Perrot, a French traveler, met him in Chicago in 1671. He characterizes Tetinchoua as being "the most powerful of Indian chiefs". Perrot stated that the Miami chief could easily manage approximately five thousand warriors as evidence of his authority and power. He never lacked guarded protection of at least forty men who were even posted around Tetinchoua's tent while he slept. Although he was a leader who hardly had personable interface with his people, he was successful in his ability to communicate through subordinates who would relay orders. Despite his highly regarded warrior reputation, he was also described as being attractive and bearing a softness to his features and mannerisms according to Father Claude Dablon.

Menominee was a Potawatomi chief and religious leader whose village on reservation lands at Twin Lakes, 5 miles (8.0 km) southwest of Plymouth in present-day Marshall County, Indiana, became the gathering place for the Potawatomi who refused to remove from their Indiana reservation lands in 1838. Their primary settlements were at present day Myers Lake and Cook Lake. Although Menominee's name and mark appear on several land cession treaties, including the Treaty of St. Mary's (1818), the Treaty of Mississinewas (1826), the Treaty of Tippecanoe (1832), and a treaty signed on December 16, 1834, he and other Potawatomi refused to take part in subsequent land cession negotiations, including the Treaty of Yellow River (1836), that directly led to the forced removal of Menominee's band from Indiana in 1838.

Hell Town is the name for a Lenape Native-American village located on Clear Creek near the abandoned town of Newville, in the U.S. state of Ohio. The site is on a high hill just north of the junction of Clear Creek and the Black Fork of the Mohican River.

Baw Beese was a Potawatomi chief who led a band that occupied the area of what is now Hillsdale, Michigan, United States. They had a base camp at the large lake that was later named for him by European-American settlers who took over the territory. In November 1840 the Potowatomi were forced to Indian Territory in Kansas under the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which was being enforced in the former Northwest Territory.