Related Research Articles

In United States law, an Alford plea, also called a Kennedy plea in West Virginia, an Alford guilty plea, and the Alford doctrine, is a guilty plea in criminal court, whereby a defendant in a criminal case does not admit to the criminal act and asserts innocence, but accepts imposition of a sentence. This plea is allowed even if the evidence to be presented by the prosecution would be likely to persuade a judge or jury to find the defendant guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. This can be caused by circumstantial evidence and testimony favoring the prosecution, and difficulty finding evidence and witnesses that would aid the defense.

Disbarment, also known as striking off, is the removal of a lawyer from a bar association or the practice of law, thus revoking their law license or admission to practice law. Disbarment is usually a punishment for unethical or criminal conduct but may also be imposed for incompetence or incapacity. Procedures vary depending on the law society; temporary disbarment may be called suspension.

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the jurisdiction.

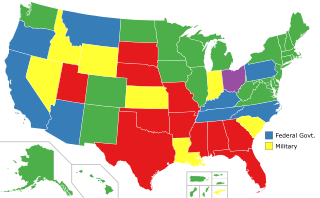

In the United States, capital punishment is a legal penalty in 27 states, throughout the country at the federal level, and in American Samoa. It is also a legal penalty for some military offenses. Capital punishment has been abolished in 23 states and in the federal capital, Washington, D.C. It is usually applied for only the most serious crimes, such as aggravated murder. Although it is a legal penalty in 27 states, 19 of them have authority to execute death sentences, with the other 8, as well as the federal government and military, subject to moratoriums.

Capital punishment is a legal punishment under the criminal justice system of the United States federal government. It is the most serious punishment that could be imposed under federal law. The serious crimes that warrant this punishment include treason, espionage, murder, large-scale drug trafficking, or attempted murder of a witness, juror, or court officer in certain cases.

In the United States, habitual offender laws have been implemented since at least 1952, and are part of the United States Justice Department's Anti-Violence Strategy. These laws require a person who is convicted of an offense and who has one or two other previous serious convictions to serve a mandatory life sentence in prison, with or without parole depending on the jurisdiction. The purpose of the laws is to drastically increase the punishment of those who continue to commit offenses after being convicted of one or two serious crimes.

Skinner v. State of Oklahoma, ex rel. Williamson, 316 U.S. 535 (1942), is a unanimous United States Supreme Court ruling that held that laws permitting the compulsory sterilization of criminals are unconstitutional as it violates a person's rights given under the 14th Amendment of the United States Constitution, specifically the Equal Protection Clause and the Due Process Clause. The relevant Oklahoma law applied to "habitual criminals" but excluded white-collar crimes from carrying sterilization penalties.

Capital punishment in India is the highest legal penalty for crimes under the country's main substantive penal legislation, the Indian Penal Code, as well as other laws. Executions are carried out by hanging as the primary method of execution per Section 354(5) of the Criminal Code of Procedure, 1973 is "Hanging by the neck until dead", and is imposed only in the 'rarest of cases'.

Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005), is a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States in which the Court held that it is unconstitutional to impose capital punishment for crimes committed while under the age of 18. The 5–4 decision overruled Stanford v. Kentucky, in which the court had upheld execution of offenders at or above age 16, and overturned statutes in 25 states.

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962), is the first landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court in which the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution was interpreted to prohibit criminalization of particular acts or conduct, as contrasted with prohibiting the use of a particular form of punishment for a crime. In Robinson, the Court struck down a California law that criminalized being addicted to narcotics.

Thompson v. Oklahoma, 487 U.S. 815 (1988), was the first case since the moratorium on capital punishment was lifted in the United States in which the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the death sentence of a minor on grounds of "cruel and unusual punishment." The holding in Thompson was expanded on by Roper v. Simmons (2005), where the Supreme Court extended the "evolving standards" rationale to those under 18 years old.

Henry Watkins Skinner was an American death row inmate in Texas. In 1995, he was convicted of bludgeoning to death his live-in girlfriend, Twila Busby, and stabbing to death her two adult sons, Randy Busby and Elwin Caler. On March 24, 2010, twenty minutes before his scheduled execution, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a stay of execution to consider the question of whether Skinner could request testing of DNA his attorney chose not to have tested at his original trial in 1994. A third execution date for November 9, 2011, was also ultimately stayed by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals on November 7, 2011.

Ewing v. California, 538 U.S. 11 (2003), is one of two cases upholding a sentence imposed under California's three strikes law against a challenge that it constituted cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment. As in its prior decision in Harmelin v. Michigan, the United States Supreme Court could not agree on the precise reasoning to uphold the sentence. But, with the decision in Ewing and the companion case Lockyer v. Andrade, the Court effectively foreclosed criminal defendants from arguing that their non-capital sentences were disproportional to the crime they had committed.

James R. Winchester is an American lawyer and judge who has served as on the Oklahoma Supreme Court for district 5 since 2000. He had two-year terms as chief justice of the Supreme Court beginning in 2007 and 2017.

Capital punishment in Connecticut formerly existed as an available sanction for a criminal defendant upon conviction for the commission of a capital offense. Since the 1976 United States Supreme Court decision in Gregg v. Georgia until Connecticut repealed capital punishment in 2012, Connecticut had only executed one person, Michael Bruce Ross in 2005. Initially, the 2012 law allowed executions to proceed for those still on death row and convicted under the previous law, but on August 13, 2015, the Connecticut Supreme Court ruled that applying capital punishment only for past cases was unconstitutional.

Scott Allen Hain was the last person executed in the United States for crimes committed as a juvenile. Hain was executed by Oklahoma for a double murder–kidnapping he committed when he was 17 years old.

Napoleon Bonaparte Johnson was born on January 17, 1891, in Maysville, Oklahoma. He was the oldest child of John Wade and Sarah Johnson, who had three other children, as well. John Johnson was half Cherokee, and his wife was white, making Napoleon and his siblings one-quarter Cherokee. The father was a professional stock trader and an elder in a local Presbyterian church. John raised his son like any other native Cherokee boy and saw to it that he started his education in a local Presbyterian mission school. He moved to Claremore in 1905, which he called his home most of his life. His formal education ended with a Bachelor of Laws (LL.B.) degree at Cumberland University.

Sharp v. Murphy, 591 U.S. ___ (2020), was a Supreme Court of the United States case of whether Congress disestablished the Muscogee (Creek) Nation reservation. After holding the case from the 2018 term, the case was decided on July 9, 2020, in a per curiam decision following McGirt v. Oklahoma that, for the purposes of the Major Crimes Act, the reservations were never disestablished and remain Indian country.

McGirt v. Oklahoma, 591 U.S. ___ (2020), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case which held that the domain reserved for the Muscogee Nation by Congress in the 19th century has never been disestablished and constitutes Indian country for the purposes of the Major Crimes Act, meaning that the State of Oklahoma has no right to prosecute American Indians for crimes allegedly committed therein. The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals applied the McGirt rationale to rule nine other Indigenous nations had not been disestablished. As a result, almost the entirety of the eastern half of what is now the State of Oklahoma remains Indian country, meaning that criminal prosecutions of Native Americans for offenses therein falls outside the jurisdiction of Oklahoma’s court system. In these cases, jurisdiction properly vests within the Indigenous judicial systems and the federal district courts under the Major Crimes Act.

Compulsory sterilization of disabled people in the U.S. prison system was permitted in the United States from 1907 to the 1960s, during which approximately 60,000 people were sterilized, two-thirds of these people being women. During this time, compulsory sterilization was motivated by eugenics. There is a lengthy history when it comes to compulsory sterilization in the United States and legislation allowing compulsory sterilization pertaining to developmentally disabled people, the U.S. prison system, and marginalized communities.

References

- ↑ Family Search. "Monroe Osborn. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Harlow, Victor E. Makers of Government in Oklahoma. Harlow Publishing Co., Oklahoma City. (1930) p.210. Accessed April 13, 2020.

- ↑ "Thirty-Two County Attorneys." The Sooner Magazine. May 1935. p. 192. Accessed April 13, 2020.

- ↑ "Gen. Schley Sworn In." Chronicling America. Evening Star(Washington, D.C.) October 19, 1937. Accessed July 19, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Leonard, Arthur S. Sexuality and the Law: American Law and Society. ISBN 0-8240-3421-X. Routledge. New York 1993. pp. 4-9. Accessed July 20, 2020.