The Virginia Defense Force (VDF) is the official state defense force of Virginia, one of the three components of Virginia's state military along with the Virginia National Guard which includes the Virginia Army National Guard, the Virginia Air National Guard, and the unorganized militia. As of 2023, the VDF has approximately 275 personnel. The VDF is the descendant of the Virginia State Guard, the Virginia Regiment, and ultimately the Colonial Virginia militia of the Virginia Colony.

The Massachusetts National Guard is the National Guard component for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Founded as the Massachusetts Bay Colonial Militia on December 13, 1636, it contains the oldest units in the United States Army. What is today's Massachusetts National Guard evolved through many different forms. Originally founded as a defensive militia for Puritan colonists in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the militia evolved into a highly organized and armed fighting force. The Massachusetts militia served as a central organ of the New England revolutionary fighting force during the early American Revolution and a major component in the Continental Army under George Washington.

The Broad Street Riot was a massive brawl that occurred in Boston, Massachusetts, on June 11, 1837, between Irish Americans and Yankee firefighters. An estimated 800 people were involved in the actual fighting, with at least 10,000 spectators egging them on. Nearby homes were sacked and vandalized, and the occupants beaten. Many on both sides were seriously injured, but no immediate deaths resulted from the violence. After raging for hours, the riot was quelled when Mayor Samuel Eliot called in the state militia.

The 7th Regiment of the New York Militia, aka the "Silk Stocking" regiment, was an infantry regiment in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Also known as the "Blue-Bloods" due to the disproportionate number of its members who were part of New York City's social elite, the 7th Militia was a pre-war New York Militia unit that was mustered into federal service for the Civil War.

The 14th Regiment New York State Militia was a volunteer militia regiment from the City of Brooklyn, New York. It is primarily known for its service in the American Civil War from April 1861 to 6 May 1864, although it later served in the Spanish–American War and World War I.

The 71st New York Infantry Regiment is an organization of the New York State Guard. Formerly, the 71st Infantry was a regiment of the New York State Militia and then the Army National Guard from 1850 to 1993. The regiment was not renumbered during the early 1920s Army reorganization due to being broken up to staff other units from 1917 to 1919, and never received a numerical designation corresponding to that of a National Guard regiment.

The 11th New York Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment of the Union Army in the early years of the American Civil War. The regiment was organized in New York City in May 1861 as a Zouave regiment, known for its unusual dress and drill style, by Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth, a personal friend of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln. Drawn from the ranks of the city's many volunteer fire companies, the unit was known alternately as the Ellsworth Zouaves, First Fire Zouaves, First Regiment New York Zouaves, and U.S. National Guards.

The Newport Artillery Company of Newport, Rhode Island was chartered in 1741 by the Rhode Island General Assembly during the reign of King George II of Great Britain. It is the oldest military unit in the United States operating under its original charter, and the company maintains a museum in its historic armory. The company has served in wars ranging from the French and Indian War to the First World War. Individual members of the Company have served in every war fought by the United States.

The 211th Military Police Battalion is a unit of the Massachusetts Army National Guard. Its Headquarters and Headquarters Detachment is descended from the First Corps of Cadets, initially formed in 1741. It is one of several National Guard units with colonial roots. Its motto is Monstrat Viam – "It Points the Way." While it has served in five wars, the sub-unit's primary contribution to Massachusetts and to the United States was as an officer-producing institution for new regiments from the Revolutionary War through World War II.

The First Corps of Cadets of Massachusetts formed in 1741. Its motto is Monstrat Viam - "It Points the Way." While it has served in several wars, the sub-unit's primary contribution to Massachusetts and to the United States was as an officer-producing institution for new regiments from the Revolutionary War through World War II.

The units of the Arkansas Militia in the Civil War to which the current Arkansas National Guard has a connection include the Arkansas State Militia, Home Guard, and State Troop regiments raised by the State of Arkansas. Like most of the United States, Arkansas had an organized militia system before the American Civil War. State law required military service of most male inhabitants of a certain age. Following the War with Mexico, the Arkansas militia experienced a decline, but as sectional frictions between the north and south began to build in the late 1850s the militia experienced a revival. By 1860 the state's militia consisted of 62 regiments divided into eight brigades, which comprised an eastern division and a western division. New regiments were added as the militia organization developed. Additionally, many counties and cities raised uniformed volunteer companies, which drilled more often and were better equipped than the un-uniformed militia. These volunteer companies were instrumental in the seizure of federal installations at Little Rock and Fort Smith, beginning in February 1861.

The history of the Arkansas State Guard and the Spanish–American War begins with the reorganization of the state militia following the end of Reconstruction. In 1879 the Arkansas Legislature had abolished the office of Adjutant General in retaliation for the use of the state militia to interfere in local political matters during reconstruction. During this period the Governor's Private Secretary performed the duties of the Adjutant General as an additional duty, and the legislature provided no appropriated funds for the state guard. Several companies existed during this period, including the Quapaw Guards and the McCarthy Guard in Little Rock. In 1897 the Arkansas State Guard was reorganized to consist of four infantry regiments, two artillery batteries and a cavalry squadron. In 1897, the state provided two volunteer infantry regiments for the Spanish–American War and although these two Arkansas Volunteer Infantry Regiments were not deployed overseas and did not see actual combat, they did suffer a number of casualties from disease.

The 138th Infantry Regiment is an light infantry regiment of the United States Army and the Missouri National Guard headquartered in Kansas City, Missouri.

The 19th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

The Reading Artillerists was a militia organization formed in Reading, Pennsylvania during the late 18th century. Mustering in for the first time during the presidential era of George Washington, members of this artillery unit went on to serve tours of duty in the War of 1812, Mexican–American War and, as members of the Union Army during the American Civil War, before later disbanding.

The 5th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Militia was a peacetime infantry regiment that was activated for federal service in the Union army for three separate tours during the American Civil War. In the years immediately preceding the war and during its first term of service, the regiment consisted primarily of companies from Essex County as well as Boston and Charlestown.

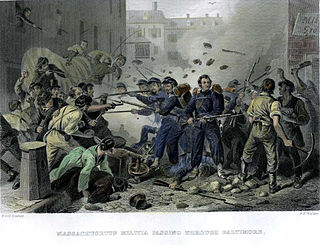

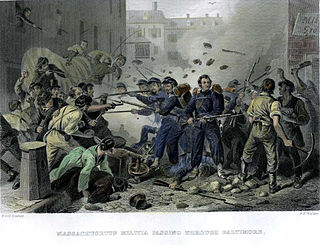

The 6th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Militia was a peacetime infantry regiment that was activated for federal service in the Union army for three separate terms during the American Civil War (1861-1865). The regiment gained notoriety as the first unit in the Union Army to suffer fatal casualties in action during the Civil War in the Baltimore Riot and the first militia unit to arrive in Washington D.C., in response to President Abraham Lincoln's initial call for 75,000 troops. Private Luther C. Ladd of the 6th Massachusetts is often referred to as the first Union soldier killed in action during the war.

The United States Zouave Cadets was a short-lived zouave unit of the Illinois militia that has been credited as the force behind the surge in popularity of zouave infantry in the United States and Confederate States in the mid-19th century. The United States Zouave Cadets were formed by Elmer Ellsworth in 1859 from the National Guard Cadets of Chicago, established three years earlier. The unit's 1860 tour of the eastern United States popularized the distinctive zouave appearance and customs, directly and indirectly inspiring the formation of dozens of similar units on the eve of the American Civil War.

The Montgomeryshire Militia, later the Royal Montgomeryshire Rifles, was an auxiliary regiment reorganised in the Welsh county of Montgomeryshire during the 18th Century from earlier precursor units. Primarily intended for home defence, it served in Great Britain and Ireland during Britain's major wars. It later became part of the South Wales Borderers until it was disbanded in 1908.