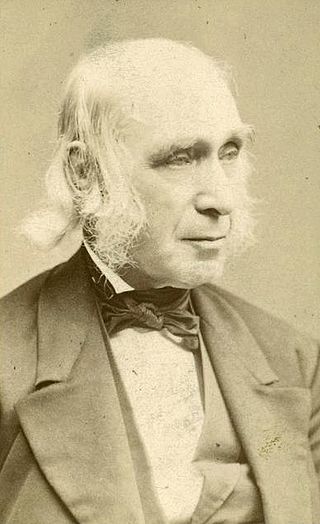

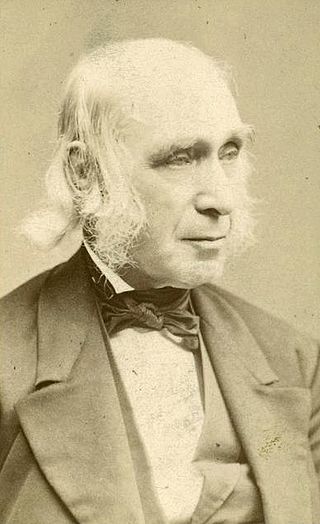

Amos Bronson Alcott was an American teacher, writer, philosopher, and reformer. As an educator, Alcott pioneered new ways of interacting with young students, focusing on a conversational style, and avoided traditional punishment. He hoped to perfect the human spirit and, to that end, advocated a plant-based diet. He was also an abolitionist and an advocate for women's rights.

Louisa May Alcott was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet best known for writing the novel Little Women (1868) and its sequels Good Wives (1869), Little Men (1871), and Jo's Boys (1886). Raised in New England by her transcendentalist parents, Abigail May and Amos Bronson Alcott, she grew up among many well-known intellectuals of the day, including Margaret Fuller, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau. Encouraged by her family, Louisa began writing from an early age.

Little Women is a coming-of-age novel written by American novelist Louisa May Alcott, originally published in two volumes, in 1868 and 1869. The story follows the lives of the four March sisters—Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy—and details their passage from childhood to womanhood. Loosely based on the lives of the author and her three sisters, it is classified as an autobiographical or semi-autobiographical novel.

Persuasion is the last novel completed by the English author Jane Austen. It was published on 20 December 1817, along with Northanger Abbey, six months after her death, although the title page is dated 1818.

Abigail May Alcott Nieriker was an American artist and the youngest sister of Louisa May Alcott. She was the basis for the character Amy in her sister's semi-autobiographical novel Little Women (1868). She was named after her mother, Abigail May, and first called Abba, then Abby, and finally May, which she asked to be called in November 1863 when in her twenties.

Little Men: Life at Plumfield with Jo's Boys, is a children's novel by American author Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888), which was first published in 1871 by Roberts Brothers. The book reprises characters from her 1868–69 two-volume novel Little Women, and acts as a sequel in the unofficial Little Women trilogy. The trilogy ends with Alcott's 1886 novel Jo's Boys, and How They Turned Out: A Sequel to "Little Men". Alcott's story recounts the life of Jo Bhaer and her husband as they run a school and educate the various children at Plumfield. The teaching methods used at Plumfield reflect transcendentalist ideals followed by Alcott's father, Bronson Alcott. Book education is combined with learning about morals and nature as the children learn through experience. Paradoxes in the story serve to emphasize Alcott's views on social norms.

The Wayside is a historic house in Concord, Massachusetts. The earliest part of the home may date to 1717. Later it successively became the home of the young Louisa May Alcott and her family, who named it Hillside, author Nathaniel Hawthorne and his family, and children's writer Margaret Sidney. It became the first site with literary associations acquired by the National Park Service and is now open to the public as part of Minute Man National Historical Park.

An Old-Fashioned Girl is a novel by Louisa May Alcott first published in 1869, which follows the adventures of Polly Milton, a young country girl, who is visiting her wealthy city friends, the Shaws. The novel shows how Polly remains true to herself despite the pressure the Shaws' world puts on her shoulders.

Eight Cousins, or The Aunt-Hill was published in 1875 by American novelist Louisa May Alcott. It was originally published as a serial in St. Nicholas and is part of the Little Women Series. It is the story of Rose Campbell, who has been recently orphaned and resides with her maiden great aunts, the matriarchs of her wealthy family near Boston, until her guardian, Uncle Alec, returns from abroad to take over her care. Through his unorthodox theories about child-rearing, she becomes happier and healthier while finding her place in her family of seven boy cousins and numerous aunts and uncles. She also makes friends with Phebe, her aunts' young housemaid. Eight Cousins received both favorable and unfavorable reviews in the early days of its publication. Reviews focused on Alcott's stylistic tone as well as the portrayal of characters and realism. In Eight Cousins, Alcott discusses transcendental education, child-rearing, and social differences.

Jo's Boys, and How They Turned Out: A Sequel to "Little Men" is a novel by American author Louisa May Alcott, first published in 1886. The novel is the final book in the unofficial Little Women series. In it, the March sisters' children and the original students of Plumfield, now grown, are caught up in real world troubles as they work towards careers and pursue love.

A Long Fatal Love Chase is a 1866 novel by Louisa May Alcott published posthumously in 1995. Two years before the publication of Little Women, Alcott uncharacteristically experimented with the style of the thriller and submitted the result, A Long Fatal Love Chase, to her publisher. The manuscript was rejected, and it remained unpublished before being bought, restored and published to acclaim in 1995.

Work: A Story of Experience, originally serialized and first published in book form in 1873, is a semi-autobiographical novel by Louisa May Alcott, the author of Little Women. It is set in the times before and after the American Civil War. The protagonist, Christie Devon, leaves her home to make a living on her own. She goes from job to job, eventually marries, and becomes a social activist when her husband dies. Alcott wrote the book over the course of several years and based it in part on her own experiences as a young woman in the workforce. Following publication, contemporary critical reviews were mixed, with some reviewers praising the plot's execution and others criticizing it. The novel's themes include women's participation in the workforce, domesticity and equality, personal independence, social reform, and mental health.

Under the Lilacs is a children's novel by Louisa May Alcott and is part of the Little Women Series. It was first published as a serialized story in St. Nicholas magazine in 1877-1878. It was first published in book form by Roberts Brothers in 1878. The plot follows twelve-year-old Ben Brown, a circus runaway who makes friends with the Moss family. He also becomes friends with Miss Celia and her brother Thornton, and Miss Celia eventually allows Ben to live at her house.

Elizabeth Sewall Alcott was one of the two younger sisters of Louisa May Alcott. She was born in 1835 and died at the age of 22 from scarlet fever.

Anna Bronson Alcott Pratt was the elder sister of American novelist Louisa May Alcott. She was the basis for the character Margaret "Meg" of Little Women (1868), her sister's classic, semi-autobiographical novel.

Rose in Bloom is a novel by Louisa May Alcott published in 1876 and is a sequel to Eight Cousins. It depicts the story of a nineteenth-century girl, Rose Campbell, finding her way in society, seeking a profession in philanthropy, and finding a marriage partner. Considered enjoyable by some readers and dull by others, the novel received generally positive reviews. Its themes include philanthropy, independence in women, the impact of society, and class differences.

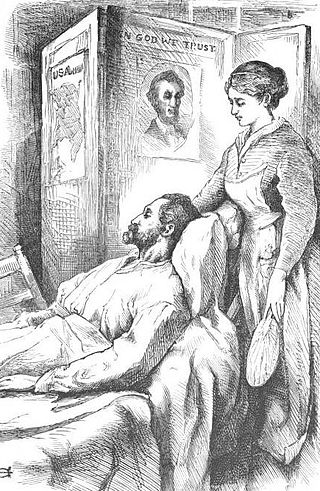

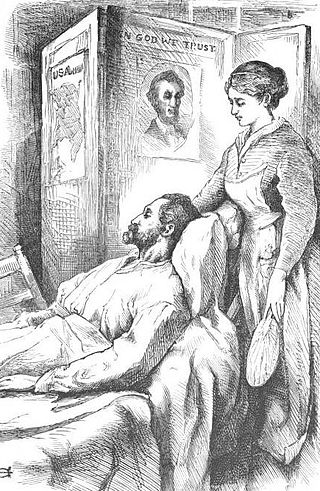

Hospital Sketches (1863) is a compilation of four sketches based on letters Louisa May Alcott sent home during the six weeks she spent as a volunteer nurse for the Union Army during the American Civil War in Georgetown.

Jack and Jill: A Village Story by Louisa May Alcott is a children's book originally serialized in St. Nicholas magazine December 1879–October 1880 and belongs to the Little Women Series. Parts of it were written during the death of May Nieriker. The novel takes place in the fictionalized New England town of Harmony Village. Jack and Jill is the story of two friends named Jack and Janey and tells of the aftermath of a serious sledding accident. After publication, the novel received reviews comparing it to Little Women and praising its portrayal of reality, while other reviews criticized its romance. Later, parts of the book were adapted into a Christmas play. Authors and professors analyzing Jack and Jill emphasize Alcott's portrayals of gender, disability, and education.

Behind a Mask, or A Woman's Power is a novella written by American author Louisa May Alcott. The novella was originally published in 1866 under the pseudonym of A. M. Barnard in The Flag of Our Union. Set in Victorian era Britain, the story follows Jean Muir, the deceitful governess of the wealthy Coventry family. With expert manipulation, Jean Muir obtains the love, respect, and eventually the fortune of the Coventry family.

A Modern Mephistopheles is a gothic thriller published by the Roberts Brothers in 1877 and written by Louisa May Alcott. It is based on Goethe's Faust and contains stylistic elements Alcott used earlier in her writing career. The novel follows Felix Canaris and Gladys, two young people whose lives are manipulated by a wealthy semi-invalid Jasper Helwyze, who seeks to undermine their relationship for psychological experimentation. Under Helwyze's direction, Canaris and Gladys marry. Gladys and Canaris eventually overcome Helwyze's influence on them.