Concubinage is an interpersonal and sexual relationship between two people in which the couple does not want to, or cannot, enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarded as similar, but mutually exclusive.

Jewellery consists of decorative items worn for personal adornment such as brooches, rings, necklaces, earrings, pendants, bracelets, and cufflinks. Jewellery may be attached to the body or the clothes. From a western perspective, the term is restricted to durable ornaments, excluding flowers for example. For many centuries metal such as gold often combined with gemstones, has been the normal material for jewellery, but other materials such as glass, shells and other plant materials may be used.

Balthild, also spelled Bathilda, Bauthieult or Baudour, was queen consort of Neustria and Burgundy by marriage to Clovis II, the King of Neustria and Burgundy (639–658), and regent during the minority of her son, Chlothar III. Her hagiography was intended to further her successful candidature for sainthood.

The House of the Vettii is a domus located in the Roman town Pompeii, which was preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. The house is named for its owners, two successful freedmen: Aulus Vettius Conviva, an Augustalis, and Aulus Vettius Restitutus. Its careful excavation has preserved almost all of the wall frescos, which were completed following the earthquake of 62 AD, in the manner art historians term the Pompeiian Fourth Style. The House of Vetti is located in region VI, near the Vesuvian Gate, bordered by the Vicolo di Mercurio and the Vicolo dei Vettii. The house is one of the largest domus in Pompeii, spanning the entire southern section of block 15. The plan is fashioned in a typical Roman domus with the exception of a tablinum, which is not included. There are twelve mythological scenes across four cubiculum and one triclinium. The house was reopened to tourists in January 2023 after two decades of restoration.

Homosexuality in ancient Rome often differs markedly from the contemporary West. Latin lacks words that would precisely translate "homosexual" and "heterosexual". The primary dichotomy of ancient Roman sexuality was active / dominant / masculine and passive / submissive / feminine. Roman society was patriarchal, and the freeborn male citizen possessed political liberty (libertas) and the right to rule both himself and his household (familia). "Virtue" (virtus) was seen as an active quality through which a man (vir) defined himself. The conquest mentality and "cult of virility" shaped same-sex relations. Roman men were free to enjoy sex with other males without a perceived loss of masculinity or social status as long as they took the dominant or penetrative role. Acceptable male partners were slaves and former slaves, prostitutes, and entertainers, whose lifestyle placed them in the nebulous social realm of infamia, so they were excluded from the normal protections afforded to a citizen even if they were technically free. Freeborn male minors were off limits at certain periods in Rome.

Slavery in ancient Rome played an important role in society and the economy. Unskilled or low-skill slaves labored in the fields, mines, and mills with few opportunities for advancement and little chance of freedom. Skilled and educated slaves—including artisans, chefs, domestic staff and personal attendants, entertainers, business managers, accountants and bankers, educators at all levels, secretaries and librarians, civil servants, and physicians—occupied a more privileged tier of servitude and could hope to obtain freedom through one of several well-defined paths with protections under the law. The possibility of manumission and subsequent citizenship was a distinguishing feature of Rome's system of slavery, resulting in a significant and influential number of freedpersons in Roman society.

In the Middle Ages, the Volga trade route connected Northern Europe and Northwestern Russia with the Caspian Sea and the Sasanian Empire, via the Volga River. The Rus used this route to trade with Muslim countries on the southern shores of the Caspian Sea, sometimes penetrating as far as Baghdad. The powerful Volga Bulgars formed a seminomadic confederation and traded through the Volga river with Viking people of Rus' and Scandinavia and with the southern Byzantine Empire Furthermore, Volga Bulgaria, with its two cities Bulgar and Suvar east of what is today Moscow, traded with Russians and the fur-selling Ugrians. Chess was introduced to Medieval Rus via the Caspian-Volga trade routes from Persia and Arabia.

The Lupanar is the ruined building of an ancient Roman brothel in the city of Pompeii. It is of particular interest for the erotic paintings on its walls, and is also known as the Lupanare Grande or the "Purpose-Built Brothel" in the Roman colony. Pompeii was closely associated with Venus, the ancient Roman goddess of love, sex, and fertility, and therefore a mythological figure closely tied to prostitution.

The Temple of Isis is a Roman temple dedicated to the Egyptian goddess Isis. This small and almost intact temple was one of the first discoveries during the excavation of Pompeii in 1764. Its role as a Hellenized Egyptian temple in a Roman colony was fully confirmed with an inscription detailed by Francisco la Vega on July 20, 1765. Original paintings and sculptures can be seen at the Museo Archaeologico in Naples; the site itself remains on the Via del Tempio di Iside. In the aftermath of the temple's discovery many well-known artists and illustrators swarmed to the site.

The Bible contains many references to slavery, which was a common practice in antiquity. Biblical texts outline sources and the legal status of slaves, economic roles of slavery, types of slavery, and debt slavery, which thoroughly explain the institution of slavery in Israel in antiquity. The Bible stipulates the treatment of slaves, especially in the Old Testament. There are also references to slavery in the New Testament.

Pompeii was a city in what is now the municipality of Pompei, near Naples, in the Campania region of Italy. Along with Herculaneum, Stabiae, and many surrounding villas, the city was buried under 4 to 6 m of volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

The gens Barbatia was a minor plebeian family at Ancient Rome. The only member of this gens mentioned in history is Marcus Barbatius Philippus, a runaway slave who became a friend of Caesar, and subsequently obtained the praetorship under Marcus Antonius. Others are known from inscriptions.

Slavery was common in the early Roman Empire and Classical Greece. It was legal in the Byzantine Empire but it was transformed significantly from the 4th century onward as slavery came to play a diminished role in the economy. Laws gradually diminished the power of slaveholders and improved the rights of slaves by restricting a master's right to abuse, prostitute, expose, and kill slaves. Slavery became rare after the first half of 7th century. From 11th century, semi-feudal relations largely replaced slavery. Under the influence of Christianity, views of slavery shifted: by the 10th century slaves were viewed as potential citizens, rather than property or chattel. Slavery was also seen as "an evil contrary to nature, created by man's selfishness", although it remained legal.

The Boscoreale Treasure is a large collection of exquisite silver and gold Roman objects discovered in the ruins of the ancient Villa della Pisanella at Boscoreale, near Pompeii, southern Italy. Consisting of over a hundred pieces of silverware, as well as gold coins and jewellery, it is now mostly kept at the Louvre Museum in Paris, although parts of the treasure can also be found at the British Museum.

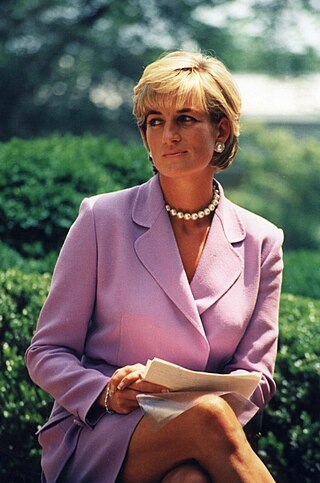

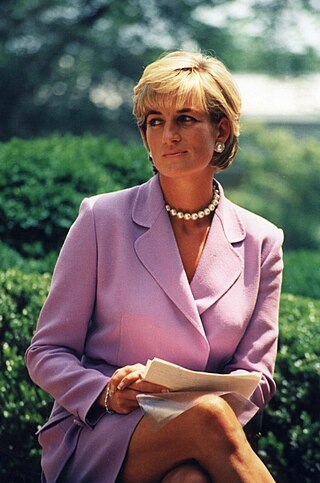

Diana, Princess of Wales, owned a collection of jewels both as a member of the British royal family and as a private individual. These were separate from the coronation and state regalia of the crown jewels. Most of her jewels were either presents from foreign royalty, on loan from Queen Elizabeth II, wedding presents, purchased by Diana herself, or heirlooms belonging to the Spencer family.

Ancillae (plural) were female house slaves in ancient Rome, as well as in Europe during the Middle Ages.

In classical Islamic law, a concubine was an unmarried slave-woman with whom her master engaged in sexual relations. Concubinage was widely accepted by Muslim scholars until the abolition of slavery in the 20th-century. Most modern Muslims, both scholars and laypersons, believe that Islam no longer permits concubinage and that sexual relations are religiously permissible only within marriage.

In ancient Rome, contubernium was a quasi-marital relationship between two slaves or between a slave (servus) and a free person who was usually a former slave or the child of a former slave. A slave involved in such a relationship was called contubernalis, the basic and general meaning of which was "companion".

Freedmen in ancient Rome existed as a distinct social class (liberti or libertini), with former slaves granted freedom and rights through the legal process of manumission. The Roman practice of slavery utilized slaves for both production and domestic labour, overseen by their wealthy masters. Urban and domestic slaves especially could achieve high levels of education, acting as agents and representatives of their masters' affairs and finances. Within Roman law there was a set of practices for freeing trusted slaves, granting them a limited form of Roman citizenship or Latin rights. These freed slaves were known in Latin as liberti (freedmen), and formed a class set apart from freeborn Romans. While freedmen were barred from some forms of social mobility in Roman society, many achieved high levels of wealth and status. Liberti were an important part of the "most economically active and innovative entrepreneurial class" in the Roman Empire. The legal and social status of freedmen remained a point of cultural and legal contention throughout the Republic and Empire.