Related Research Articles

A gladiator was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals. Some gladiators were volunteers who risked their lives and their legal and social standing by appearing in the arena. Most were despised as slaves, schooled under harsh conditions, socially marginalized, and segregated even in death.

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican state of ancient Rome. It is generally understood to mean the period and territory ruled by the Romans following Octavian's assumption of sole rule under the Principate in 27 BC. It included territories in Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia and was ruled by emperors. The fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD conventionally marks the end of classical antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages.

Ancient Roman architecture adopted the external language of classical ancient Greek architecture for the purposes of the ancient Romans, but was different from Greek buildings, becoming a new architectural style. The two styles are often considered one body of classical architecture. Roman architecture flourished in the Roman Republic and to an even greater extent under the Empire, when the great majority of surviving buildings were constructed. It used new materials, particularly Roman concrete, and newer technologies such as the arch and the dome to make buildings that were typically strong and well engineered. Large numbers remain in some form across the former empire, sometimes complete and still in use today.

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. Liturgy can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and participation in the sacred through activities reflecting praise, thanksgiving, remembrance, supplication, or repentance. It forms a basis for establishing a relationship with God.

Sextus Julius Frontinus was a prominent Roman civil engineer, author, soldier and senator of the late 1st century AD. He was a successful general under Domitian, commanding forces in Roman Britain, and on the Rhine and Danube frontiers. A novus homo, he was consul three times. Frontinus ably discharged several important administrative duties for Nerva and Trajan. However, he is best known to the post-Classical world as an author of technical treatises, especially De aquaeductu, dealing with the aqueducts of Rome.

Citizenship in ancient Rome was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in Ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, traditions, and cultural practices. There existed several different types of citizenship, determined by one's gender, class, and political affiliations, and the exact duties or expectations of a citizen varied throughout the history of the Roman Empire.

In ancient Rome, the Latin term municipium referred to a town or city. Etymologically, the municipium was a social contract among municipes, or citizens of the town. The duties were a communal obligation assumed by the municipes in exchange for the privileges and protections of citizenship. Every citizen was a municeps.

Roman funerary practices include the Ancient Romans' religious rituals concerning funerals, cremations, and burials. They were part of time-hallowed tradition, the unwritten code from which Romans derived their social norms. Elite funeral rites, especially processions and public eulogies, gave the family opportunity to publicly celebrate the life and deeds of the deceased, their ancestors, and the family's standing in the community. Sometimes the political elite gave costly public feasts, games and popular entertainments after family funerals, to honour the departed and to maintain their own public profile and reputation for generosity. The Roman gladiator games began as funeral gifts for the deceased in high status families.

In Ancient Rome, the Latin term civitas, according to Cicero in the time of the late Roman Republic, was the social body of the cives, or citizens, united by law. It is the law that binds them together, giving them responsibilities on the one hand and rights of citizenship on the other. The agreement has a life of its own, creating a res publica or "public entity", into which individuals are born or accepted, and from which they die or are ejected. The civitas is not just the collective body of all the citizens, it is the contract binding them all together, because each of them is a civis.

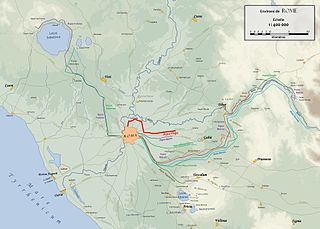

The Aqua Virgo was one of the eleven Roman aqueducts that supplied the city of ancient Rome. It was completed in 19 BC by Marcus Agrippa, during the reign of the emperor Augustus and was built mainly to supply the contemporaneous Baths of Agrippa in the Campus Martius.

The Romans constructed aqueducts throughout their Republic and later Empire, to bring water from outside sources into cities and towns. Aqueduct water supplied public baths, latrines, fountains, and private households; it also supported mining operations, milling, farms, and gardens.

In ancient Rome, the curiales were initially the leading members of a gentes (clan) of the city of Rome. Their roles were both civil and sacred. Each gens curialis had a leader, called a curio. The whole arrangement of assemblies was presided over by the curio maximus.

Sanitation in ancient Rome, acquired from the Etruscans, was very advanced compared to other ancient cities and provided water supply and sanitation services to residents of Rome. Although there were many sewers, public latrines, baths and other sanitation infrastructure, disease was still rampant. The baths are known to symbolise the "great hygiene of Rome".

Opera publica is the Latin name used by Ancient Rome for the building of public works, construction or engineering projects carried out under the direction of the state on behalf of the community. The term "public works" is a calque of the Latin. Public works in the Roman Empire were not merely buildings for the conduct of the business of running the city, but all buildings for public use. Therefore, amphitheatres, aqueducts, temples, basilicae, theatres, fora, arches, defensive walls, harbours, bridges, thermae, fountains, roads, circuses, markets, and cloacae were classified as opera publica.

Euergetism (or evergetism, from the Greek εὐεργετέω, "do good deeds") was the ancient practice of high-status and wealthy individuals in society distributing part of their wealth to the community. This practice was also part of the patron-client relation system of Roman society. The term was coined by French historian André Boulanger and subsequently used in the works of Paul Veyne.

The Aqua Julia is a Roman aqueduct built in 33 BC by Agrippa under Augustus to supply the city of Rome. It was repaired and expanded by Augustus from 11–4 BC.

In Ancient Rome, the Aqua Alsietina was the earlier of the two western Roman aqueducts, erected sometime around 2 BC, during the reign of emperor Augustus. It was the only water supply for the Transtiberine region, on the right bank of the river Tiber until the Aqua Traiana was built.

De aquaeductu is a two-book official report given to the emperor Nerva or Trajan on the state of the aqueducts of Rome, and was written by Sextus Julius Frontinus at the end of the 1st century AD. It is also known as De Aquis or De Aqueductibus Urbis Romae. It is the earliest official report of an investigation made by a distinguished citizen on Roman engineering works to have survived. Frontinus had been appointed Water Commissioner by the emperor Nerva in AD 96.

The Curator Aquarum was a Roman official responsible for managing Rome's water supply and distributing free grain. Curators were appointed by the emperor. The first curator was Agrippa. Another notable Curator Aquarum was Frontinus, a Roman engineer.

References

- ↑ Bispham, Edward, From Asculum to Actium: The Municipalization of Italy from the Social War to Augustus (Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 15 and 26.

- ↑ In the early imperial era, around 10% of Rome's aqueduct water fed 591 public fountains; see Keenan-Jones, Duncan; Motta, Davide; Garcia, Marcelo H; Fouke, Bruce, W. "Travertine-based estimates of the amount of water supplied by ancient Rome's Anio Novus aqueduct", Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Science Direct, Volume 3, September 2015, pp. 1 - 10 (accessed online January 30 2021)

- ↑ The relevant MS and print versions of Frontinus (1.3 and 1.78) are uncertain in meaning. See Aicher, Peter J., "Terminal Display Fountains ("Mostre") and the Aqueducts of Ancient Rome", Phoenix, 47 (Winter, 1993), pp. 339-352, Classical Association of Canada, https://doi.org/10.2307/1088729 Stable URL https://www.jstor.https://doi.org/10.2307/1088729 (registration required - accessed April 29, 2021)

- ↑ Grey, Cam, Constructing Communities in the Late Roman Countryside, 2011 pp. 183, 195 ISBN 978-1-107-01162-5

- ↑ Pharr, Clyde, The Theodosian Code, Twelfth Reprinting, 2010, pp. 577, 592 ISBN 978-1-58477-146-3

- ↑ Jones, A.H.M.. The Later Roman Empire Vol. I, p. 749 ISBN 0-8018-3353-1

- ↑ Grey, pp. 189-197, 203-204, 209

- ↑ Grey, pp. 191-193

- ↑ Jones, LRE Vol. I, 1964, p. 66