N.S.-Funk ("National Socialist Radio") was a German magazine published from Munich and Berlin between 1933 and 1939. It provided listings of radio programming schedules and reviewed programmes in accordance with the party line.

N.S.-Funk ("National Socialist Radio") was a German magazine published from Munich and Berlin between 1933 and 1939. It provided listings of radio programming schedules and reviewed programmes in accordance with the party line.

In 1932, the Nazi party leadership decided to start a radio magazine of its own to compete with the various existing radio magazines. [1] The publication was founded in February 1933 as the first official Nazi radio magazine, tasked with providing listings of radio programming schedules in Germany and reviewing them in accordance with the party line. [2] [3] [4] It replaced the radio magazine Der Deutsche Sender ('The German Broadcaster'), as the former Reich Association of German Broadcasters (RDR) was taken over by the Reich Broadcasting Chamber. [5] It was published from Munich and Berlin until 1939, [6] when it was merged into the magazine Volksfunk ('People's Radio'). [7]

N.S.-Funk was a central organ of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) and the Reich Broadcasting Chamber (a body within the Reich Chamber of Culture). [8] [5] It was published by Franz Eher Nachfolger, the central publishing body of the Nazi Party. [1] It had an editorial branch office at Zimmerstrasse 88 in Berlin. [9] [1] Heinz Frante was the editor in chief of N.S.-Funk. [2] [1] Over time, N.S.-Funk grew in popularity, by early 1937 it reached a circulation of about a quarter million copies. [2]

In contrast to other contemporary German radio magazines N.S.-Funk was published in various regional editions, covering each of the different broadcasting districts, such as Bavaria, Berlin, Silesia, East Prussia, Saar-Palatinate, Central Germany, Western Germany, Southwest Germany, North Germany and South Germany. [2] [1] It was an illustrated weekly. [9]

During the prolonged Volkssender-Aktion propaganda campaign, each copy of N.S.-Funk would typically carry one or two pages dedicated to the announcements of the campaign. [10] The publication Funktechnischer Vorwärts functioned as the radio technical edition of N.S.-Funk and Volksfunk. [11]

Gottfried Feder was a German civil engineer, a self-taught economist, and one of the early key members of the Nazi Party and its economic theoretician. It was one of his lectures, delivered in 1919, that drew Adolf Hitler into the party.

Max Amann was a high-ranking member of the Nazi Party, a German politician, businessman and art collector, including of looted art. He was the first business manager of the Nazi Party and later became the head of Eher Verlag, the official Nazi Party publishing house. He was also the Reichsleiter for the press. After the war ended, Amann was arrested by Allied troops. Amann was deemed a Hauptschuldiger and sentenced to ten years in a labour camp. He was released in 1953. Amann died in poverty in Munich.

Reichsleiter was the second-highest political rank in the Nazi Party (NSDAP), subordinate only to the office of Führer. Reichsleiter also functioned as a paramilitary rank within the NSDAP and was the highest rank attainable in any Nazi organisation.

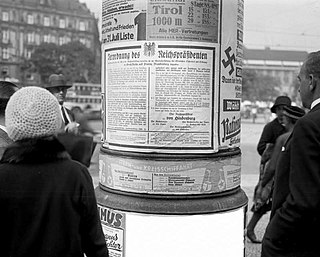

The 1932 Prussian coup d'état or Preußenschlag took place on 20 July 1932, when Reich President Paul von Hindenburg, at the request of Franz von Papen, then Reich Chancellor of Germany, replaced the legal government of the Free State of Prussia with von Papen as Reich Commissioner. A second decree the same day transferred executive power in Prussia to the Reich Minister of the Armed Forces Kurt von Schleicher and restricted fundamental rights.

The Nazi Party/Foreign Organization was a branch of the Nazi Party and the 43rd and only non-territorial Gau ("region") of the Party. In German, the organization is referred to as NSDAP/AO, "AO" being the abbreviation of the German compound word Auslands-Organisation. Although Auslands-Organisation would be correctly written as one word, the Nazis chose an obsolete spelling with a hyphen.

Wilhelm Weiss was, in the time of the Third Reich, an SA-Obergruppenführer as well as editor-in-chief of the NSDAP's official newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter

Franz Eher Nachfolger GmbH was the central publishing house of the Nazi Party and one of the largest book and periodical firms during the Nazi Germany. It was acquired by the party on 17 December 1920 for 115,000 Papiermark.

Deutsche Zeitung in Norwegen was an Oslo-based daily newspaper published in Norway during the Second World War. It was published by the subsidiary Europa-Verlag of the Nazi-controlled Franz Eher Nachfolger, and had a circulation of about 40,000 copies. The paper served as a model for the Amsterdam-based Deutsche Zeitung in den Niederlanden.

The Free State of Brunswick was a state of the German Reich in the time of the Weimar Republic. It was formed after the abolition of the Duchy of Brunswick in the course of the German Revolution of 1918–19. Its capital was Braunschweig (Brunswick).

The Brown House was the name given to the Munich mansion located between the Karolinenplatz and Königsplatz, known before as the Palais Barlow, which was purchased in 1930 for the Nazis. They converted the structure into the headquarters of the National Socialist German Workers' Party. Its name comes from early Nazi Party uniforms, which were brown. Many leading Nazis, including Adolf Hitler, maintained offices there throughout the party's existence. It was destroyed by Allied bombing raids during World War II.

The Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, also known simply as the Ministry of Propaganda, controlled the content of the press, literature, visual arts, film, theater, music and radio in Nazi Germany.

The Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft was a national network of German regional public radio and television broadcasting companies active from 1925 until 1945. RRG's broadcasts were receivable in all parts of Germany and were used extensively for Nazi propaganda after 1933.

The Secret Meeting of 20 February 1933 was a secret meeting held by Adolf Hitler and 20 to 25 industrialists at the official residence of the President of the Reichstag Hermann Göring in Berlin. Its purpose was to raise funds for the election campaign of the Nazi Party.

Karl Astel was an Alter Kämpfer, rector of the University of Jena, a racial scientist, and also involved in the German Nazi Eugenics program.

Lying press is a pejorative and disparaging political term used largely for the printed press and the mass media at large. It is used as an essential part of propaganda and is thus usually dishonest or at least not based on careful research.

Alfred-Ingemar Berndt was a German Nazi journalist, writer and close collaborator of Reich Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda Joseph Goebbels.

Heinrich Werlé was a German choir director, organist and music critic.

Wolfgang Diewerge was a Nazi propagandist in Joseph Goebbels' Reich Ministry of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda. His special field was anti-Semitic public relations, especially in connection with trials abroad, which could be exploited for propaganda purposes. He also played an essential role in the preparation of a show trial against Herschel Grynszpan, whose assassination attempt on a German embassy employee in Paris had been used by the Nazis as a trigger for the November pogroms in 1938. In 1941, his pamphlets on the so-called Kaufman Plan and the Soviet Union were published in print runs of millions. After the war, Diewerge managed to re-enter politics via the FDP North Rhine-Westphalia. However, the intervention of the British occupation authorities and a commission of the FDP's Federal Executive Committee put an abrupt end to this intermezzo. In 1966 Diewerge was convicted of perjury for his statements made under oath about the Grynszpan trial planned by the National Socialists. After all, he was involved in the Flick donations affair as managing director of two associations.