Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavement is the placement of a person into slavery, and the person is called a slave or an enslaved person.

The Liberty Bell, previously called the State House Bell or Old State House Bell, is an iconic symbol of American independence located in Philadelphia. Originally placed in the steeple of Pennsylvania State House, now known as Independence Hall, the Liberty Bell today is located across the street from Independence Hall in the Liberty Bell Center in Independence National Historical Park.

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slavery was established throughout European colonization in the Americas. From 1526, during the early colonial period, it was practiced in what became Britain's colonies, including the Thirteen Colonies that formed the United States. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property that could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until abolition in 1865, and issues concerning slavery seeped into every aspect of national politics, economics, and social custom. In the decades after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, many of slavery's economic and social functions were continued through segregation, sharecropping, and convict leasing. Involuntary servitude as a punishment for crime is still legal in the United States.

The Slave Trade Act 1807, officially An Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom prohibiting the slave trade in the British Empire. Although it did not automatically emancipate those enslaved at the time, it encouraged British action to press other nation states to abolish their own slave trades. It took effect on 1 May 1807, after 18 years of trying to pass an abolition bill.

The Corwin Amendment is a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution that has never been adopted, but owing to the absence of a ratification deadline, could theoretically still be adopted by the state legislatures. It would have shielded slavery within the states from the federal constitutional amendment process and from abolition or interference by Congress.

The slave codes were laws relating to slavery and enslaved people, specifically regarding the Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery in the Americas.

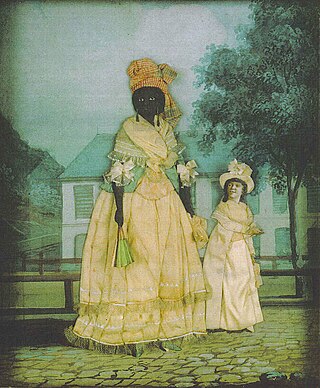

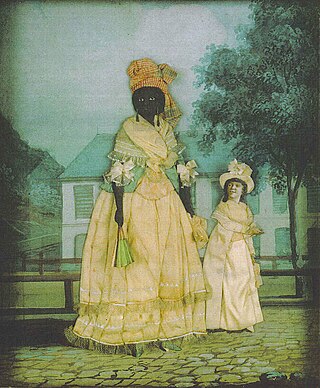

In the British colonies in North America and in the United States before the abolition of slavery in 1865, free Negro or free Black described the legal status of African Americans who were not enslaved. The term was applied both to formerly enslaved people (freedmen) and to those who had been born free, whether of African or mixed descent.

Confederate History Month is a month designated by seven state governments in the Southern United States for the purpose of recognizing and honoring the Confederate States of America. April has traditionally been chosen, as Confederate Memorial Day falls during that month in many of these states. The designation of a month as Confederate History Month began in 1994.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), colloquially known as the Blacksonian, is a Smithsonian Institution museum located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., in the United States. It was established in 2003 and opened its permanent home in 2016 with a ceremony led by President Barack Obama.

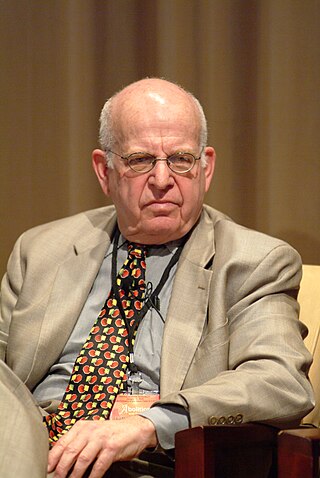

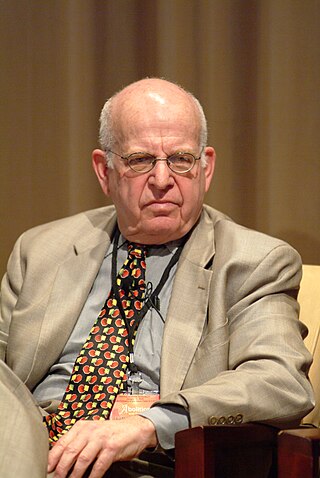

Ira Berlin was an American historian, professor of history at the University of Maryland, and former president of Organization of American Historians.

The New York Manumission Society was founded in 1785. The term "manumission" is from the Latin meaning "a hand lets go," inferring the idea of freeing a slave. John Jay, first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States as well as statesman Alexander Hamilton and the lexicographer Noah Webster, along with many slave holders among its founders. Its mandate was to promote gradual emancipation and to advocate for those already emancipated. New York ended slavery in 1827. The Society was disbanded in 1849, after its mandate was perceived to have been fulfilled. the society battled against the slave trade, and for the eventual emancipation of all the slaves in the state. In 1787, they founded the African Free School to teach children of slaves and free people of color, preparing them for life as free citizens. The school produced leaders from within New York's Black community.

The trafficking of enslaved Africans to what became New York began as part of the Dutch slave trade. The Dutch West India Company trafficked eleven enslaved Africans to New Amsterdam in 1626, with the first slave auction held in New Amsterdam in 1655. With the second-highest proportion of any city in the colonies, more than 42% of New York City households enslaved African people by 1703, often as domestic servants and laborers. Others worked as artisans or in shipping and various trades in the city. Enslaved Africans were also used in farming on Long Island and in the Hudson Valley, as well as the Mohawk Valley region.

When the Dutch and Swedes established colonies in the Delaware Valley of what is now Pennsylvania, in North America, they quickly imported enslaved Africans for labor; the Dutch also transported them south from their colony of New Netherland. Enslavement was documented in this area as early as 1639. William Penn and the colonists who settled in Pennsylvania tolerated slavery. Still, the English Quakers and later German immigrants were among the first to speak out against it. Many colonial Methodists and Baptists also opposed it on religious grounds. During the Great Awakening of the late 18th century, their preachers urged slaveholders to free their slaves. High British tariffs in the 18th century discouraged the importation of additional slaves, and encouraged the use of white indentured servants and free labor.

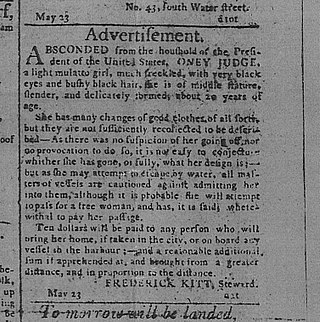

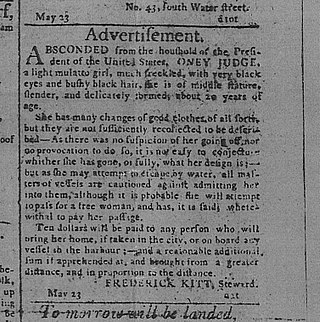

The President's House in Philadelphia was the third U.S. Presidential Mansion. George Washington occupied it from November 27, 1790, to March 10, 1797, and John Adams occupied it from March 21, 1797, to May 30, 1800.

Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, owned more than 600 slaves during his adult life. Jefferson freed two slaves while he lived, and five others were freed after his death, including two of his children from his relationship with his slave Sally Hemings. His other two children with Hemings were allowed to escape without pursuit. After his death, the rest of the slaves were sold to pay off his estate's debts.

Slave breeding was the practice in slave states of the United States of slave owners systematically forcing slaves to have children to increase their wealth. It included coerced sexual relations between enslaved men and women or girls, forced pregnancies of enslaved women and girls due to forced inter inbreeding with fellow slaves in hopes of producing relatively stronger future slaves. The objective was for slave owners to increase the number of people they enslaved without incurring the cost of purchase, and to fill labor shortages caused by the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade.

The treatment of slaves in the United States often included sexual abuse and rape, the denial of education, and punishments like whippings. Families were often split up by the sale of one or more members, usually never to see or hear of each other again.

Vermont was amongst the first places to abolish slavery by constitutional dictum. Although estimates place the number of slaves at 25 in 1770, slavery was banned outright upon the founding of Vermont in July 1777, and by a further provision in its Constitution, existing male slaves became free at the age of 21 and females at the age of 18. Not only did Vermont's legislature agree to abolish slavery entirely, it also moved to provide full voting rights for African-American males. According to the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture, "Vermont's July 1777 declaration was not entirely altruistic either. While it did set an independent tone from the 13 colonies, the declaration's wording was vague enough to let Vermont's already-established slavery practices continue."

Manisha Sinha is an Indian-born American historian, and the Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut. She is the author of The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition (2016), which won the Frederick Douglass Book Prize. and, most recently The Rise and Fall of the Second American Republic: Reconstruction, 1860-1920 (2024).

Slavery as a positive good in the United States was the prevailing view of Southern politicians and intellectuals just before the American Civil War, as opposed to seeing it as a crime against humanity or a necessary evil. They defended the legal enslavement of people for their labor as a benevolent, paternalistic institution with social and economic benefits, an important bulwark of civilization, and a divine institution similar or superior to the free labor in the North.