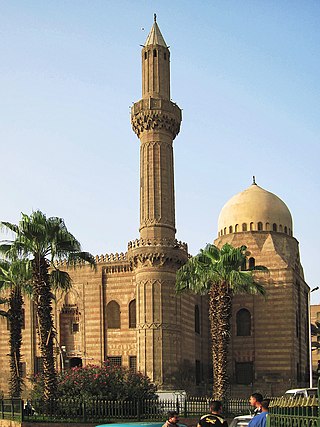

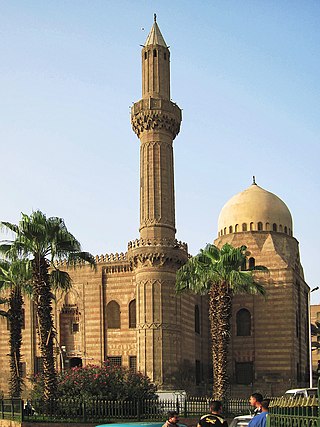

Al-Rifa'i Mosque is located in Citadel Square, adjacent to the Cairo Citadel. Its name is derived from the Ali Abu Shubbak who is buried in the mosque. Now, it is also the royal mausoleum of Muhammad Ali's family. The building is located opposite the Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hassan, which dates from around 1361, and was architecturally conceived as a complement to the older structure as part of a vast campaign by the 19th century rulers of Egypt to both associate themselves with the perceived glory of earlier periods in Egypt's Islamic history and modernize the city.

An iwan is a rectangular hall or space, usually vaulted, walled on three sides, with one end entirely open. The formal gateway to the iwan is called pishtaq, a Persian term for a portal projecting from the facade of a building, usually decorated with calligraphy bands, glazed tilework, and geometric designs. Since the definition allows for some interpretation, the overall forms and characteristics can vary greatly in terms of scale, material, or decoration.

The Citadel of Cairo or Citadel of Saladin is a medieval Islamic-era fortification in Cairo, Egypt, built by Salah ad-Din (Saladin) and further developed by subsequent Egyptian rulers. It was the seat of government in Egypt and the residence of its rulers for nearly 700 years from the 13th century until the construction of Abdeen Palace in the 19th century. Its location on a promontory of the Mokattam hills near the center of Cairo commands a strategic position overlooking the city and dominating its skyline. When it was constructed it was among the most impressive and ambitious military fortification projects of its time. It is now a preserved historic site, including mosques and museums.

The Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo, Egypt is considered one of the greatest museums in the world, with its exceptional collection of rare woodwork and plaster artefacts, as well as metal, ceramic, glass, crystal, and textile objects of all periods, from all over the Islamic world.

There have been many architectural styles used in Egyptian buildings over the centuries, including Ancient Egyptian architecture, Greco-Roman architecture, Islamic architecture, and modern architecture.

The Muhammad Ali Mosque or Mosque of Muhammad Ali is a historic mosque in Cairo, Egypt. It was commissioned by Muhammad Ali Pasha and built between 1832 and 1857. Situated in the Cairo Citadel in a position overlooking the city, it is one of the most visible mosques and landmarks in the skyline of Cairo. Unlike the traditional Cairene architecture that preceded it, the mosque was built in an entirely Ottoman and European-influenced style, further setting it apart from other monuments. It is sometimes called the Alabaster Mosque due to the prominent use of alabaster as a covering for its walls.

The City of the Dead, or Cairo Necropolis, also referred to as theQarafa, is a series of vast Islamic-era necropolises and cemeteries in Cairo, Egypt. They extend to the north and to the south of the Cairo Citadel, below the Mokattam Hills and outside the historic city walls, covering an area roughly 4 miles (6.4 km) long. They are included in the UNESCO World Heritage Site of "Historic Cairo".

The Qalawun complex is a massive pious complex in Cairo, Egypt, built by Sultan al-Mansur Qalawun from 1284 to 1285. It is located at Bayn al-Qasrayn on al-Mu'izz street and like many other pious complexes includes a hospital (bimaristan), a madrasa and mausoleum. Despite controversy surrounding its construction, this building is widely regarded as one of the major monuments of Islamic Cairo and of Mamluk architecture, notable for the size and scope of its contributions to legal scholarship and charitable operations as well as for the richness of its architecture.

The Aqmar Mosque, was built in Cairo, Egypt, as a neighborhood mosque by the Fatimid vizier al-Ma'mun al-Bata'ihi in 1125-6 CE. The mosque is situated on what was once the main avenue and ceremonial heart of Cairo, known today as al-Mu'izz Street, in the immediate neighborhood of the former Fatimid caliphal palaces. The mosque is an important monument of Fatimid architecture and of historic Cairo due to the exceptional decoration of its exterior façade and the innovative design of its floor plan.

Al-Azhar Mosque, known in Egypt simply as al-Azhar, is a mosque in Cairo, Egypt in the historic Islamic core of the city. Commissioned as the new capital of the Fatimid Caliphate in 970, it was the first mosque established in a city that eventually earned the nickname "the City of a Thousand Minarets". Its name is usually thought to derive from az-Zahrāʾ, a title given to Fatimah, the daughter of Muhammad.

The Fatimid architecture that developed in the Fatimid Caliphate (909–1167 CE) of North Africa combined elements of eastern and western architecture, drawing on Abbasid architecture, Byzantine, Ancient Egyptian, Coptic architecture and North African traditions; it bridged early Islamic styles and the medieval architecture of the Mamluks of Egypt, introducing many innovations.

Mamluk architecture was the architectural style that developed under the Mamluk Sultanate (1250–1517), which ruled over Egypt, the Levant, and the Hijaz from their capital, Cairo. Despite their often tumultuous internal politics, the Mamluk sultans were prolific patrons of architecture and contributed enormously to the fabric of historic Cairo. The Mamluk period, particularly in the 14th century, oversaw the peak of Cairo's power and prosperity. Their architecture also appears in cities such as Damascus, Jerusalem, Aleppo, Tripoli, and Medina.

Max Herz (born as Herz Miksa was a Hungarian architect, conservator, museum director and architectural historian, active in Egypt.

Al-Sayyida Nafisa Mosque is a mosque in al-Sayyida Nafisa district, a section of the larger historic necropolis called al-Qarafa in Cairo, Egypt. It is built to commemorate Sayyida Nafisa, an Islamic saint and member of the family of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. She was the great-granddaughter of Hasan, one of the Prophet Muhammad's two grandsons. The mosque contains her mausoleum, also known as a mashhad. Along with the necropolis around it, the mosque is listed as part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Historic Cairo.

Sulayman Pasha al-Khadem Mosque, also known as Sariat al-Jabal Mosque, is a historical mosque established in 1528 by Suleiman Pasha Al-Khadem, one of the Ottoman rulers of Egypt. It is located inside the Cairo Citadel at the top of Mount Mokattam, and originally erected for the use of the janissaries stationed in the northern enclosure. It is the first mosque established in Egypt in Ottoman architectural style.

Al-Mahmoudia Mosque or the Mosque of Mahmud Pasha is a historic mosque in the city of Cairo, Egypt. It is located at the Salah al-Din Square in the Citadel of Cairo area, in front of Bab al-Azab gate of the citadel. There are Sultan Hassan Mosque and Al-Rifa'i Mosque to the east.

Ottoman architecture in Egypt, during the period after the Ottoman conquest in 1517, continued the traditions of earlier Mamluk architecture but was influenced by the architecture of the Ottoman Empire. Important new features introduced into local architecture included the pencil-style Ottoman minaret, central-domed mosques, new tile decoration and other characteristics of Ottoman architecture. Architectural patronage was reduced in scale compared to previous periods, as Egypt became an Ottoman province instead of the center of an empire. One of the most common types of building erected in Cairo during this period is the sabil-kuttab.

The Mashhad of Sayyida Ruqayya, sometimes referred to as the Mausoleum or Tomb of Sayyida Ruqayya, is a 12th-century Islamic religious shrine and mosque in Cairo, Egypt. It was erected in 1133 CE as a memorial to Ruqayya bint Ali, a member of the Islamic prophet Muhammad's family. It is also notable as one of the few and most important Fatimid-era mausoleums preserved in Cairo today.

The Mausoleum of Shajar al-Durr is a mausoleum housing the tomb of the female Ayyubid sultan Shajar al-Durr in Cairo, Egypt. It is located on al-Khalifa Street or Shurafa Street, in a neighbourhood on the edge of the al-Qarafa cemeteries. Its construction was commissioned by Shajar al-Durr herself and it is believed to have been built in the Islamic year 648 AH. Shajar al-Durr was notable for being the only female Muslim ruler in Egyptian history and for playing a crucial role in the transition from Ayyubid rule to Mamluk rule. The mausoleum serves as the formal resting place of the queen and commemorates her legacy. Architectural features of this structure, along with the broader architectural patronage of Shajar al-Durr, influenced future Mamluk architecture.

The Mosque of Sayyida Sukayna or Mosque of Sayyida Sakina is a historic mosque in Cairo, Egypt. According to an apocryphal tradition, it contains the tomb of Sakina, a daughter of Husayn. The current building dates from 1904. It is located in the historic al-Khalifa neighbourhood, on the outskirts of Cairo's Southern Cemetery.