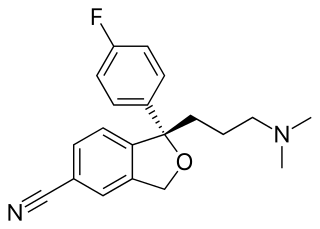

In stereochemistry, stereoisomerism, or spatial isomerism, is a form of isomerism in which molecules have the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms (constitution), but differ in the three-dimensional orientations of their atoms in space. This contrasts with structural isomers, which share the same molecular formula, but the bond connections or their order differs. By definition, molecules that are stereoisomers of each other represent the same structural isomer.

The structural formula of a chemical compound is a graphic representation of the molecular structure, showing how the atoms are possibly arranged in the real three-dimensional space. The chemical bonding within the molecule is also shown, either explicitly or implicitly. Unlike other chemical formula types, which have a limited number of symbols and are capable of only limited descriptive power, structural formulas provide a more complete geometric representation of the molecular structure. For example, many chemical compounds exist in different isomeric forms, which have different enantiomeric structures but the same molecular formula. There are multiple types of ways to draw these structural formulas such as: Lewis Structures, condensed formulas, skeletal formulas, Newman projections, Cyclohexane conformations, Haworth projections, and Fischer projections.

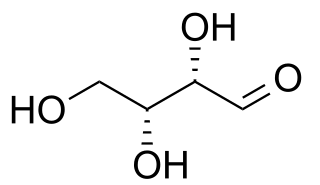

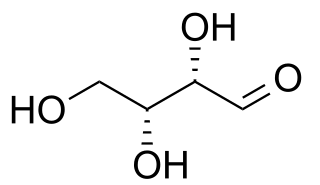

In chemistry, the Fischer projection, devised by Emil Fischer in 1891, is a two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional organic molecule by projection. Fischer projections were originally proposed for the depiction of carbohydrates and used by chemists, particularly in organic chemistry and biochemistry. The use of Fischer projections in non-carbohydrates is discouraged, as such drawings are ambiguous and easily confused with other types of drawing. The main purpose of Fischer projections is to show the chirality of a molecule and to distinguish between a pair of enantiomers. Some notable uses include drawing sugars and depicting isomers.

In stereochemistry, diastereomers are a type of stereoisomer. Diastereomers are defined as non-mirror image, non-identical stereoisomers. Hence, they occur when two or more stereoisomers of a compound have different configurations at one or more of the equivalent (related) stereocenters and are not mirror images of each other. When two diastereoisomers differ from each other at only one stereocenter, they are epimers. Each stereocenter gives rise to two different configurations and thus typically increases the number of stereoisomers by a factor of two.

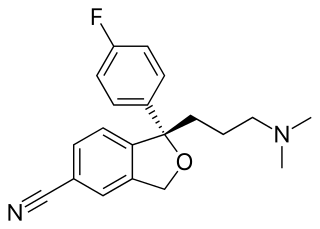

The skeletal formula, or line-angle formula or shorthand formula, of an organic compound is a type of molecular structural formula that serves as a shorthand representation of a molecule's bonding and some details of its molecular geometry. A skeletal formula shows the skeletal structure or skeleton of a molecule, which is composed of the skeletal atoms that make up the molecule. It is represented in two dimensions, as on a piece of paper. It employs certain conventions to represent carbon and hydrogen atoms, which are the most common in organic chemistry.

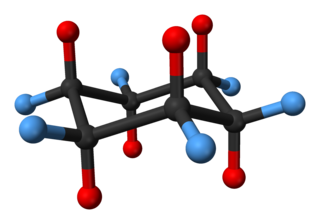

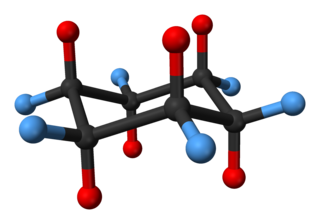

Cyclohexane conformations are any of several three-dimensional shapes adopted by molecules of cyclohexane. Because many compounds feature structurally similar six-membered rings, the structure and dynamics of cyclohexane are important prototypes of a wide range of compounds.

In chemistry, conformational isomerism is a form of stereoisomerism in which the isomers can be interconverted just by rotations about formally single bonds. While any two arrangements of atoms in a molecule that differ by rotation about single bonds can be referred to as different conformations, conformations that correspond to local minima on the potential energy surface are specifically called conformational isomers or conformers. Conformations that correspond to local maxima on the energy surface are the transition states between the local-minimum conformational isomers. Rotations about single bonds involve overcoming a rotational energy barrier to interconvert one conformer to another. If the energy barrier is low, there is free rotation and a sample of the compound exists as a rapidly equilibrating mixture of multiple conformers; if the energy barrier is high enough then there is restricted rotation, a molecule may exist for a relatively long time period as a stable rotational isomer or rotamer. When the time scale for interconversion is long enough for isolation of individual rotamers, the isomers are termed atropisomers. The ring-flip of substituted cyclohexanes constitutes another common form of conformational isomerism.

In chemistry an eclipsed conformation is a conformation in which two substituents X and Y on adjacent atoms A, B are in closest proximity, implying that the torsion angle X–A–B–Y is 0°. Such a conformation can exist in any open chain, single chemical bond connecting two sp3-hybridised atoms, and it is normally a conformational energy maximum. This maximum is often explained by steric hindrance, but its origins sometimes actually lie in hyperconjugation.

In chemistry, a molecule experiences strain when its chemical structure undergoes some stress which raises its internal energy in comparison to a strain-free reference compound. The internal energy of a molecule consists of all the energy stored within it. A strained molecule has an additional amount of internal energy which an unstrained molecule does not. This extra internal energy, or strain energy, can be likened to a compressed spring. Much like a compressed spring must be held in place to prevent release of its potential energy, a molecule can be held in an energetically unfavorable conformation by the bonds within that molecule. Without the bonds holding the conformation in place, the strain energy would be released.

In organic chemistry, ring strain is a type of instability that exists when bonds in a molecule form angles that are abnormal. Strain is most commonly discussed for small rings such as cyclopropanes and cyclobutanes, whose internal angles are substantially smaller than the idealized value of approximately 109°. Because of their high strain, the heat of combustion for these small rings is elevated.

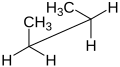

Pentane interference or syn-pentane interaction is the steric hindrance that the two terminal methyl groups experience in one of the chemical conformations of n-pentane. The possible conformations are combinations of anti conformations and gauche conformations and are anti-anti, anti-gauche+, gauche+ - gauche+ and gauche+ - gauche− of which the last one is especially energetically unfavorable. In macromolecules such as polyethylene pentane interference occurs between every fifth carbon atom. The 1,3-diaxial interactions of cyclohexane derivatives is a special case of this type of interaction, although there are additional gauche interactions shared between substituents and the ring in that case. A clear example of the syn-pentane interaction is apparent in the diaxial versus diequatorial heats of formation of cis 1,3-dialkyl cyclohexanes. Relative to the diequatorial conformer, the diaxial conformer is 2-3 kcal/mol higher in energy than the value that would be expected based on gauche interactions alone. Pentane interference helps explain molecular geometries in many chemical compounds, product ratios, and purported transition states. One specific type of syn-pentane interaction is known as 1,3 allylic strain or.

In organic chemistry, hyperconjugation refers to the delocalization of electrons with the participation of bonds of primarily σ-character. Usually, hyperconjugation involves the interaction of the electrons in a sigma (σ) orbital with an adjacent unpopulated non-bonding p or antibonding σ* or π* orbitals to give a pair of extended molecular orbitals. However, sometimes, low-lying antibonding σ* orbitals may also interact with filled orbitals of lone pair character (n) in what is termed negative hyperconjugation. Increased electron delocalization associated with hyperconjugation increases the stability of the system. In particular, the new orbital with bonding character is stabilized, resulting in an overall stabilization of the molecule. Only electrons in bonds that are in the β position can have this sort of direct stabilizing effect — donating from a sigma bond on an atom to an orbital in another atom directly attached to it. However, extended versions of hyperconjugation can be important as well. The Baker–Nathan effect, sometimes used synonymously for hyperconjugation, is a specific application of it to certain chemical reactions or types of structures.

In organic chemistry, a staggered conformation is a chemical conformation of an ethane-like moiety abcX–Ydef in which the substituents a, b, and c are at the maximum distance from d, e, and f; this requires the torsion angles to be 60°. It is the opposite of an eclipsed conformation, in which those substituents are as close to each other as possible.

In organic chemistry, a ring flip is the interconversion of cyclic conformers that have equivalent ring shapes that results in the exchange of nonequivalent substituent positions. The overall process generally takes place over several steps, involving coupled rotations about several of the molecule's single bonds, in conjunction with minor deformations of bond angles. Most commonly, the term is used to refer to the interconversion of the two chair conformers of cyclohexane derivatives, which is specifically referred to as a chair flip, although other cycloalkanes and inorganic rings undergo similar processes.

In organic chemistry, the anomeric effect or Edward-Lemieux effect is a stereoelectronic effect that describes the tendency of heteroatomic substituents adjacent to a heteroatom within a cyclohexane ring to prefer the axial orientation instead of the less hindered equatorial orientation that would be expected from steric considerations. This effect was originally observed in pyranose rings by J. T. Edward in 1955 when studying carbohydrate chemistry.

A cyclic compound is a term for a compound in the field of chemistry in which one or more series of atoms in the compound is connected to form a ring. Rings may vary in size from three to many atoms, and include examples where all the atoms are carbon, none of the atoms are carbon, or where both carbon and non-carbon atoms are present. Depending on the ring size, the bond order of the individual links between ring atoms, and their arrangements within the rings, carbocyclic and heterocyclic compounds may be aromatic or non-aromatic; in the latter case, they may vary from being fully saturated to having varying numbers of multiple bonds between the ring atoms. Because of the tremendous diversity allowed, in combination, by the valences of common atoms and their ability to form rings, the number of possible cyclic structures, even of small size numbers in the many billions.

Asymmetric induction describes the preferential formation in a chemical reaction of one enantiomer or diastereoisomer over the other as a result of the influence of a chiral feature present in the substrate, reagent, catalyst or environment. Asymmetric induction is a key element in asymmetric synthesis.

A-values are numerical values used in the determination of the most stable orientation of atoms in a molecule, as well as a general representation of steric bulk. A-values are derived from energy measurements of the different cyclohexane conformations of a monosubstituted cyclohexane chemical. Substituents on a cyclohexane ring prefer to reside in the equatorial position to the axial. The difference in Gibbs free energy (ΔG) between the higher energy conformation and the lower energy conformation is the A-value for that particular substituent.

In chemistry, isomers are molecules or polyatomic ions with identical molecular formula – that is, same number of atoms of each element – but distinct arrangements of atoms in space. Isomerism refers to the existence or possibility of isomers.

Carbohydrate conformation refers to the overall three-dimensional structure adopted by a carbohydrate (saccharide) molecule as a result of the through-bond and through-space physical forces it experiences arising from its molecular structure. The physical forces that dictate the three-dimensional shapes of all molecules—here, of all monosaccharide, oligosaccharide, and polysaccharide molecules—are sometimes summarily captured by such terms as "steric interactions" and "stereoelectronic effects".