An amphora is a type of container with a pointed bottom and characteristic shape and size which fit tightly against each other in storage rooms and packages, tied together with rope and delivered by land or sea. The size and shape have been determined from at least as early as the Neolithic Period. Amphorae were used in vast numbers for the transport and storage of various products, both liquid and dry, but mostly for wine. They are most often ceramic, but examples in metals and other materials have been found. Versions of the amphorae were one of many shapes used in Ancient Greek vase painting.

Ancient Greek pottery, due to its relative durability, comprises a large part of the archaeological record of ancient Greece, and since there is so much of it, it has exerted a disproportionately large influence on our understanding of Greek society. The shards of pots discarded or buried in the 1st millennium BC are still the best guide available to understand the customary life and mind of the ancient Greeks. There were several vessels produced locally for everyday and kitchen use, yet finer pottery from regions such as Attica was imported by other civilizations throughout the Mediterranean, such as the Etruscans in Italy. There were a multitude of specific regional varieties, such as the South Italian ancient Greek pottery.

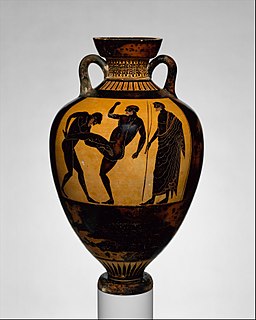

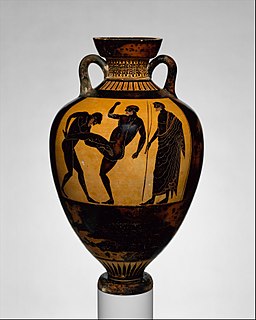

Black-figure pottery painting, also known as the black-figure style or black-figure ceramic, is one of the styles of painting on antique Greek vases. It was especially common between the 7th and 5th centuries BCE, although there are specimens dating as late as the 2nd century BCE. Stylistically it can be distinguished from the preceding orientalizing period and the subsequent red-figure pottery style.

Exekias was an ancient Greek vase painter and potter who was active in Athens between roughly 545 BC and 530 BC. Exekias worked mainly in the black-figure technique, which involved the painting of scenes using a clay slip that fired to black, with details created through incision. Exekias is regarded by art historians as an artistic visionary whose masterful use of incision and psychologically sensitive compositions mark him as one of the greatest of all Attic vase painters. The Andokides painter and the Lysippides Painter are thought to have been students of Exekias.

Red-figure vase painting is one of the most important styles of figural Greek vase painting.

The Kleophrades Painter is the name given to the anonymous red-figure Athenian vase painter, who was active from approximately 510–470 BC and whose work, considered amongst the finest of the red-figure style, is identified by its stylistic traits.

The Berlin Painter is the conventional name given to an Attic Greek vase-painter who is widely regarded as a rival to the Kleophrades Painter, among the most talented vase painters of the early 5th century BCE.

Nikosthenes was a potter of Greek black- and red-figure pottery in the time window 550–510 BC. He signed as the potter on over 120 black-figure vases, but only nine red-figure. Most of his vases were painted by someone else, called Painter N. Beazley considers the painting "slovenly and dissolute;" that is, not of high quality. In addition, he is thought to have worked with the painters Anakles, Oltos, Lydos and Epiktetos. Six's technique is believed to have been invented in Nikosthenes' workshop, possibly by Nikosthenes himself, around 530 BC. He is considered transitional between black-figure and red-figure pottery.

Psiax was an Attic vase painter of the transitional period between the black-figure and red-figure styles. His works date to circa 525 to 505 BC and comprise about 60 surviving vases, two of which bear his signature. Initially he was allocated the name "Menon Painter" by John Beazley. Only later was it realised that the artist was identical with the painters signing as "Psiax".

Panathenaic amphorae were the amphorae, large ceramic vessels, that contained the olive oil given as prizes in the Panathenaic Games. Some were ten imperial gallons and 60–70 cm (24–28 in) high. This oil came from the sacred grove of Athena at Akademia. The amphorae which held it had the distinctive form of tight handles, narrow neck and feet, and they were decorated with consistent symbols, in a standard form using the black figure technique, and continued to be so, long after the black figure style had fallen out of fashion. Some Panathenaic amphorae depicted Athena Promachos, goddess of war, advancing between columns brandishing a spear and wearing the aegis, and next to her the inscription τῶν Ἀθήνηθεν ἄθλων "(one) of the prizes from Athens". On the back of the vase was a representation of the event for which it was an award. Sometimes roosters are depicted perched on top of the columns. The significance of the roosters remains a mystery. Later amphorae also had that year's archon's name written on it making finds of those vases archaeologically important.

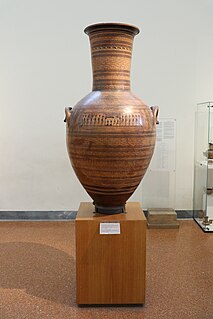

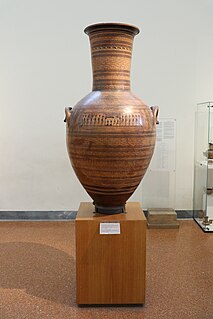

Geometric art is a phase of Greek art, characterized largely by geometric motifs in vase painting, that flourished towards the end of the Greek Dark Ages, c. 900–700 BC. Its center was in Athens, and from there the style spread among the trading cities of the Aegean. The Greek Dark Ages lasted from c. 1100 to 750 BC and include two periods, the Protogeometric period and the Geometric period, in reference to the characteristic pottery style. The vases had various uses or purposes within Greek society, including, but not limited to, funerary vases and symposium vases.

The Amasis Painter was an ancient Greek vase painter who worked in the black-figure technique. He owes his name to the signature of the potter Amasis, who signed twelve works painted by the same hand. At the time of the exhibition, "The Amasis Painter and His World" (1985), 132 vases had been attributed to this artist.

The pottery of ancient Greece has a long history and the form of Greek vase shapes has had a continuous evolution from Minoan pottery down to the Hellenistic period. As Gisela Richter puts it, the forms of these vases find their "happiest expression" in the 5th and 6th centuries BC, yet it has been possible to date vases thanks to the variation in a form’s shape over time, a fact particularly useful when dating unpainted or plain black-gloss ware.

South Italian is a designation for ancient Greek pottery fabricated in Magna Graecia largely during the 4th century BC. The fact that Greek Southern Italy produced its own red-figure pottery as early as the end of the 5th century BC was first established by Adolf Furtwaengler in 1893. Prior to that this pottery had been first designated as "Etruscan" and then as "Attic." Archaeological proof that this pottery was actually being produced in South Italy first came in 1973 when a workshop and kilns with misfirings and broken wares was first excavated at Metaponto, proving that the Amykos Painter was located there rather than in Athens.

Pottery was produced in enormous quantities in ancient Rome, mostly for utilitarian purposes. It is found all over the former Roman Empire and beyond. Monte Testaccio is a huge waste mound in Rome made almost entirely of broken amphorae used for transporting and storing liquids and other products – in this case probably mostly Spanish olive oil, which was landed nearby, and was the main fuel for lighting, as well as its use in the kitchen and washing in the baths.

The Lysippides Painter was an Attic vase painter in the black-figure style. He was active around 530 to 510 BC. His conventional name comes from a kalos inscription on a vase in the British Museum attributed to him; his real name is not known.

Melian Pithamphorae or Melian Amphorae are names for a type of large belly-handled amphorae, which were produced in the Archaic period in the Cyclades. On account of their shape and painted decoration in the Orientalising style, they are among the most famous Greek vases. The amphorae are dated to the seventh and early sixth centuries BC; the last of them was made in the 580s. They were used as grave markers with the same function as the later grave statues and reliefs and were dedicated as cult objects in sanctuaries. With the increasing importance of sculpture in these roles, the production of these vases came to an end.

The Euphiletos Painter Panathenaic Amphora is a black-figure terracotta amphora from the Archaic Period depicting a running race, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It was painted by the Euphiletos Painter as a victory prize for the Panathenaic Games in Athens in 530 BC.

The Kleophrades Panathenaic prize amphora is an Archaic period amphora by the Kleophrades Painter from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Dating to c. 500 BCE, the amphora, filled with olive oil, was the prize for a victor in the Panathenaia games in Athens. This particular amphora is a neck amphora that stands at 63.5 centimetres (25.0 in) tall.

The Dipylon Amphora is a large Ancient Greek painted vase, made around 750 BC, and is now held by the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Discovered at the Dipylon cemetery, this stylistic vessel belonging to the Geometric period is credited to an unknown artist: the Dipylon Master. The amphora is covered entirely in ornamental and geometric patterns, as well as human figures and animal-filled motifs. It is also structurally precise, being that it is as tall as it is wide. These decorations use up every inch of space, and are painted on using the black-figure technique to create the silhouetted shapes. Inspiration for the Greek vase derived not only from its intended purpose as a funerary vessel, but also from artistic remnants of Mycenaean civilization prior to its collapse around 1100 BC. The Dipylon Amphora signifies the passing of an aristocratic woman, who is illustrated along with the procession of her funeral consisting of mourning family and friends situated along the belly of the vase. The woman's nobility and status is further emphasized by the plethora of detail and characterized animals, all which remain in bands circling the neck and belly of the amphora.