Related Research Articles

Lepontic is an ancient Alpine Celtic language that was spoken in parts of Rhaetia and Cisalpine Gaul between 550 and 100 BC. Lepontic is attested in inscriptions found in an area centered on Lugano, Switzerland, and including the Lake Como and Lake Maggiore areas of Italy. Being a Celtic language, its name could derive from Proto-Celtic *leikwontio-.

The Iberian language was the language of an indigenous western European people identified by Greek and Roman sources who lived in the eastern and southeastern regions of the Iberian Peninsula in the pre-Migration Era. An ancient Iberian culture can be identified as existing between the 7th and 1st centuries BC, at least.

Celtiberian or Northeastern Hispano-Celtic is an extinct Indo-European language of the Celtic branch spoken by the Celtiberians in an area of the Iberian Peninsula between the headwaters of the Douro, Tagus, Júcar and Turia rivers and the Ebro river. This language is directly attested in nearly 200 inscriptions dated from the 2nd century BC to the 1st century AD, mainly in Celtiberian script, a direct adaptation of the northeastern Iberian script, but also in the Latin alphabet. The longest extant Celtiberian inscriptions are those on three Botorrita plaques, bronze plaques from Botorrita near Zaragoza, dating to the early 1st century BC, labeled Botorrita I, III and IV. Shorter and more fragmentary is the Novallas bronze tablet.

The Botorrita plaques are four bronze plaques discovered in Botorrita, near Zaragoza, Spain, dating to the late 2nd century BC, known as Botorrita I, II, III and IV.

The Celtiberian script is a Paleohispanic script that was the main writing system of the Celtiberian language, an extinct Continental Celtic language, which was also occasionally written using the Latin alphabet. This script is a direct adaptation of the northeastern Iberian script, the most frequently used of the Iberian scripts.

Lusitanian was an Indo-European Paleohispanic language. There has been support for either a connection with the ancient Italic languages or Celtic languages. It is known from only six sizeable inscriptions, dated from c. 1 CE, and numerous names of places (toponyms) and of gods (theonyms). The language was spoken in the territory inhabited by Lusitanian tribes, from the Douro to the Tagus rivers, territory that today falls in central Portugal and western Spain.

Hispano-Celtic is a term for all forms of Celtic spoken in the Iberian Peninsula before the arrival of the Romans. In particular, it includes:

The Continental Celtic languages are the now-extinct group of the Celtic languages that were spoken on the continent of Europe and in central Anatolia, as distinguished from the Insular Celtic languages of the British Isles and Brittany. Continental Celtic is a geographic, rather than linguistic, grouping of the ancient Celtic languages.

Tartessian is an extinct Paleo-Hispanic language found in the Southwestern inscriptions of the Iberian Peninsula, mainly located in the south of Portugal, and the southwest of Spain. There are 95 such inscriptions, the longest having 82 readable signs. Around one third of them were found in Early Iron Age necropolises or other Iron Age burial sites associated with rich complex burials. It is usual to date them to the 7th century BC and to consider the southwestern script to be the most ancient Paleo-Hispanic script, with characters most closely resembling specific Phoenician letter forms found in inscriptions dated to c. 825 BC. Five of the inscriptions occur on stelae that have been interpreted as Late Bronze Age carved warrior gear from the Urnfield culture.

The Bronze of Luzaga is a plate of 16 x 15 centimeters which has, in 8 lines, 123 Celtiberian characters engraved in the metal with a bradawl or similar, and which has 7 holes, perhaps in order to be held. Since its discovery in the late nineteenth century, it has been lost.

Botorrita is a municipality of 574 residents located in the province of Zaragoza, Aragon, Spain.

The Paleohispanic scripts are the writing systems created in the Iberian Peninsula before the Latin alphabet became the dominant script. They derive from the Phoenician alphabet, with the exception of the Greco-Iberian alphabet, which is a direct adaptation of the Greek alphabet. Some researchers believe that the Greek alphabet may also have played a role in the origin of the other Paleohispanic scripts. Most of these scripts are notable for being semi-syllabic rather than purely alphabetic.

The northeastern Iberian script, also known as Levantine Iberian or simply Iberian, was the primary means of written expression for the Iberian language. It has also been used to write Proto-Basque, as evidenced by the Hand of Irulegi. The Iberian language is also represented by the southeastern Iberian script and the Greco-Iberian alphabet. In understanding the relationship between the northeastern and southeastern Iberian scripts, some note that they are two distinct scripts with different values assigned to the same signs. However, they share a common origin, and the most widely accepted hypothesis is that the northeastern Iberian script was derived from the southeastern Iberian script. Some researchers have concluded that it is linked solely to the Phoenician alphabet, while others believe that the Greek alphabet also played a role.

The paleo-Hispanic languages are the languages of the Pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula, excluding languages of foreign colonies, such as Greek in Emporion and Phoenician in Qart Hadast. After the Roman conquest of Hispania the Paleohispanic languages, with the exception of Proto-Basque, were replaced by Latin, the ancestor of the modern Iberian Romance languages.

The Belli, also designated Beli or Belaiscos, were an ancient pre-Roman Celtic Celtiberian people who lived in the modern Spanish province of Zaragoza from the 3rd Century BC.

Gallaecian or Northwestern Hispano-Celtic is an extinct Celtic language of the Hispano-Celtic group. It was spoken by the Gallaeci in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula around the start of the 1st millennium. The region became the Roman province of Gallaecia, which is now divided between the Spanish regions of Galicia, western Asturias, the west of the Province of León, and Northern Portugal.

The Chamalières tablet is a lead tablet, six by four centimeters, that was discovered in 1971 in Chamalières, France, at the Source des Roches excavation. The tablet is dated somewhere between 50 BC and 50 AD. The text is written in the Gaulish language, with cursive Latin letters. With 396 letters grouped in 47 words, it is the third-longest extant text in Gaulish, giving it great importance in the study of this language.

Francisco Villar Liébana is a Spanish linguist, full professor of Indoeuropean linguistics at the University of Salamanca, beginning in 1979.

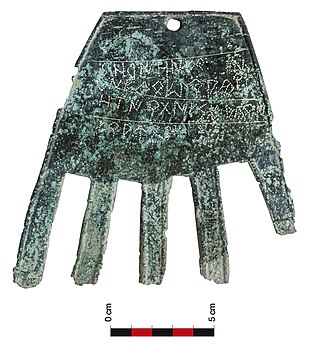

The Hand of Irulegi is a late Iron Age archaeological artifact unearthed in 2021 during excavations in the archaeological site of Irulegi (Navarre), next to the medieval castle of Irulegi, located in the municipality of Aranguren, Spain. The bronze artifact has the distinctive shape of a right hand with extended fingers. It has five separate strings of letters, probably corresponding to five or more words, carved on the side that represents the back of a hand.

Peñalba de Villastar is a Celtiberian sanctuary in the municipality of Villastar, Aragon, Spain. About 10km south of Teruel, it is located at the eastern edge of Celtic Iberia. The sanctuary is along a cliff 1500m in length, where soft white limestone and marl rock bears hundreds of inscriptions and graffiti.

References

- ↑ Francisco Beltrán Lloris , Carlos Jordán Cólera, Borja Díaz Ariño1, and Ignacio Simón Cornago. "The Novallas bronze tablet: An inscription in the Celtiberian language and the Latin alphabet from Spain." Journal of Roman Archaeology 34 (2021), pp. 713, 722. doi:10.1017/S1047759421000635

- ↑ Cólera, Carlos Jordán. "Chronica Epigraphica Celtiberica XI" Zaragoza: Institucion "Fernando el Catolico" Palaeohispanica (Zaragoza), 2022-01, Vol.22, p.275. "8. El Bronce de Novallas" p. 304.

- ↑ Cólera, Carlos Jordán. "Chronica Epigraphica Celtiberica XI" Zaragoza: Institucion "Fernando el Catolico" Palaeohispanica (Zaragoza), 2022-01, Vol.22, p.275. "8. El Bronce de Novallas" p. 305.

- ↑ Beltrán Lloris, F., Carlos Jordán Cólera, Borja Díaz Ariño1, and Ignaci, Simón Cornago. "The Novallas bronze tablet: An inscription in the Celtiberian language and the Latin alphabet from Spain." Journal of Roman Archaeology 34 (2021), 713–733, 717 doi:10.1017/S1047759421000635

- ↑ Francisco Beltrán Lloris, Carlos Jordán Cólera, Borja Díaz Ariño1, and Ignacio Simón Cornago. "The Novallas bronze tablet: An inscription in the Celtiberian language and the Latin alphabet from Spain." Journal of Roman Archaeology 34 (2021), p.714. doi:10.1017/S1047759421000635

- ↑ Francisco Beltrán Lloris , Carlos Jordán Cólera, Borja Díaz Ariño1, and Ignacio Simón Cornago. El Bronce de Novallas (Zaragoza) y la epigrafía celtibérica en alfabeto latino Museo de Zaragoza. Zaragoza, p.46 (2021)

- 1 2 3 Stifter, David. "Contributions to Celtiberian Etymology III. The Bronze of Novallas" Palaeohispanica 22. 2022. pp. 131-136

- ↑ Jordán Cólera, Carlos. "Avdintvm, una nueva forma verbal en celtibérico y sus posibles relaciones paradigmáticas (auzeti, auzanto, auz, auzimei, auzares...)" Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Cuadernos de filología clásica. Estudios griegos e indoeuropeos, 2015-05, Vol.25 (25), pp. 11-23

- 1 2 Jordán Cólera, Carlos "La forma verbal cabint del bronce celtibérico de Novallas (Zaragoza)" Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas Emerita, 2014-12, Vol.82 (2), p.327-343

- 1 2 Cólera, Carlos Jordán. "Chronica Epigraphica Celtiberica XI" Zaragoza: Institucion "Fernando el Catolico" Palaeohispanica (Zaragoza), 2022-01, Vol.22, p.275. "8. El Bronce de Novallas" p. 307.

- ↑ Cólera, Carlos Jordán. "Chronica Epigraphica Celtiberica XI" Zaragoza: Institucion "Fernando el Catolico" Palaeohispanica (Zaragoza), 2022-01, Vol.22, p.275. "8. El Bronce de Novallas" pp. 311-12.

- 1 2 Beltrán Lloris, F., Carlos Jordán Cólera, Borja Díaz Ariño1, and Ignaci, Simón Cornago. "The Novallas bronze tablet: An inscription in the Celtiberian language and the Latin alphabet from Spain." Journal of Roman Archaeology 34 (2021), 713–733, 720 doi:10.1017/S1047759421000635

- ↑ Beltrán Lloris, F., Carlos Jordán Cólera, Borja Díaz Ariño1, and Ignaci, Simón Cornago. "The Novallas bronze tablet: An inscription in the Celtiberian language and the Latin alphabet from Spain." Journal of Roman Archaeology 34 (2021), 713–733, 720-21 doi:10.1017/S1047759421000635

- 1 2 Beltrán Lloris, F., Carlos Jordán Cólera, Borja Díaz Ariño1, and Ignaci, Simón Cornago. "The Novallas bronze tablet: An inscription in the Celtiberian language and the Latin alphabet from Spain." Journal of Roman Archaeology 34 (2021), 713–733, 721 doi:10.1017/S1047759421000635

- ↑ Francisco Beltrán Lloris , Carlos Jordán Cólera, Borja Díaz Ariño1, and Ignacio Simón Cornago. "The Novallas bronze tablet: An inscription in the Celtiberian language and the Latin alphabet from Spain." Journal of Roman Archaeology 34 (2021), 713–733, 721 doi:10.1017/S1047759421000635