Vitruvius was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work titled De architectura. As the only treatise on architecture to survive from antiquity, it has been regarded since the Renaissance as the first book on architectural theory, as well as a major source on the canon of classical architecture. It is not clear to what extent his contemporaries regarded his book as original or important.

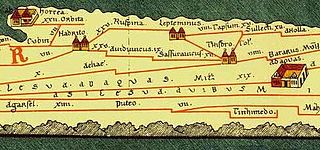

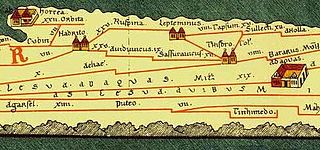

Hispellum was an ancient town of Umbria, Italy, 6 km (3.7 mi) north of Fulginiae on the road to Perusia.

Motya was an ancient and powerful city on San Pantaleo Island off the west coast of Sicily, in the Stagnone Lagoon between Drepanum and Lilybaeum. It is within the present-day commune of Marsala, Italy.

Lime plaster is a type of plaster composed of sand, water, and lime, usually non-hydraulic hydrated lime. Ancient lime plaster often contained horse hair for reinforcement and pozzolan additives to reduce the working time.

Lixus is an ancient city founded by Phoenicians before the city of Carthage. Its distinguishing feature is that it was continuously occupied from antiquity to the Islamic Era, and has ruins dating to the Phoenician, Punic, Mauretanian, Roman and Islamic periods.

Cosmatesque, or Cosmati, is a style of geometric decorative inlay stonework typical of the architecture of Medieval Italy, and especially of Rome and its surroundings. It was used most extensively for the decoration of church floors, but was also used to decorate church walls, pulpits, and bishop's thrones. The name derives from the Cosmati, the leading family workshop of craftsmen in Rome who created such geometrical marble decorations.

Soluntum or Solus was an ancient city on the Tyrrhenian coast of Sicily near present-day in the comune of Santa Flavia, Italy. The site is a major tourist attraction. The city was founded by the Phoenicians in the sixth century BC and was one of the three chief Phoenician settlements in Sicily in the archaic and classical periods. It was destroyed at the beginning of the fourth century BC and re-founded on its present site atop Monte Catalfano. At the end of the fourth century BC, Greek soldiers were settled there and in the 3rd century BC the city came under the control of the Roman Republic. Excavations took place in the 19th century and in the mid-20th century. Around half of the urban area has been uncovered and it is relatively well preserved. The remains provide a good example of an ancient city in which Greek, Roman and Punic traditions mixed.

Opus reticulatum is a facing used for concrete walls in Roman architecture from about the first century BCE to the early first century CE. They were built using small pyramid shaped tuff, a volcanic stone embedded into a concrete core. Reticulate work was also combined with a multitude of other building materials to provide polychrome colouring and other facings to form new techniques. Opus reticulatum was generally used in central and southern Italy with the exception being its rare appearance in Africa and Jericho. This was because of tuff's wider availability and ease of local transport in central Italy and Campania compared to other regions.

Opus sectile is a form of pietra dura popularized in the ancient and medieval Roman world where materials were cut and inlaid into walls and floors to make a picture or pattern. Common materials were marble, mother of pearl, and glass. The materials were cut in thin pieces, polished, then trimmed further according to a chosen pattern. Unlike tessellated mosaic techniques, where the placement of very small uniformly sized pieces forms a picture, opus sectile pieces are much larger and can be shaped to define large parts of the design.

Hellenistic art is the art of the Hellenistic period generally taken to begin with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and end with the conquest of the Greek world by the Romans, a process well underway by 146 BC, when the Greek mainland was taken, and essentially ending in 30 BC with the conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt following the Battle of Actium. A number of the best-known works of Greek sculpture belong to this period, including Laocoön and His Sons, Venus de Milo, and the Winged Victory of Samothrace. It follows the period of Classical Greek art, while the succeeding Greco-Roman art was very largely a continuation of Hellenistic trends.

Leptis or Lepcis Parva was a Phoenician colony and Carthaginian and Roman port on Africa's Mediterranean coast, corresponding to the modern town Lemta, just south of Monastir, Tunisia. In antiquity, it was one of the wealthiest cities in the region.

The House of the Faun, constructed in the 2nd century BC during the Samnite period, was a grand Hellenistic palace that was framed by peristyle in Pompeii, Italy. The historical significance in this impressive estate is found in the many great pieces of art that were well preserved from the ash of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. It is one of the most luxurious aristocratic houses from the Roman Republic, and reflects this period better than most archaeological evidence found even in Rome itself.

Opus incertum was an ancient Roman construction technique, using irregularly shaped and randomly placed uncut stones or fist-sized tuff blocks inserted in a core of opus caementicium.

Roman concrete, also called opus caementicium, was used in construction in ancient Rome. Like its modern equivalent, Roman concrete was based on a hydraulic-setting cement added to an aggregate.

Carthage National Museum is a national museum in Byrsa, Tunisia. Along with the Bardo National Museum, it is one of the two main local archaeological museums in the region. The edifice sits atop Byrsa Hill, in the heart of the city of Carthage. Founded in 1875, it houses many archaeological items from the Punic era and other periods.

A Roman mosaic is a mosaic made during the Roman period, throughout the Roman Republic and later Empire. Mosaics were used in a variety of private and public buildings, on both floors and walls, though they competed with cheaper frescos for the latter. They were highly influenced by earlier and contemporary Hellenistic Greek mosaics, and often included famous figures from history and mythology, such as Alexander the Great in the Alexander Mosaic.

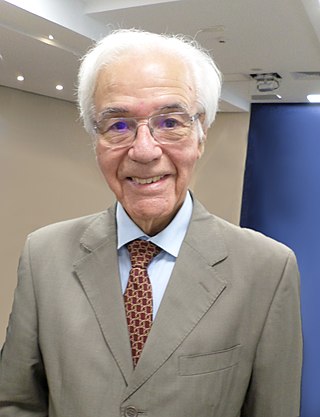

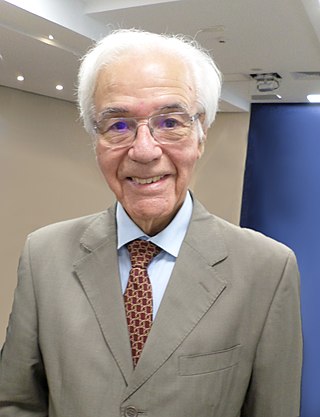

M'hamed Hassine Fantar is a professor of Ancient History of Archeology and History of Religion at Tunis University.

The mosaics of Delos are a significant body of ancient Greek mosaic art. Most of the surviving mosaics from Delos, Greece, an island in the Cyclades, date to the last half of the 2nd century BC and early 1st century BC, during the Hellenistic period and beginning of the Roman period of Greece. Hellenistic mosaics were no longer produced after roughly 69 BC, due to warfare with the Kingdom of Pontus and the subsequently abrupt decline of the island's population and position as a major trading center. Among Hellenistic Greek archaeological sites, Delos contains one of the highest concentrations of surviving mosaic artworks. Approximately half of all surviving tessellated Greek mosaics from the Hellenistic period come from Delos.

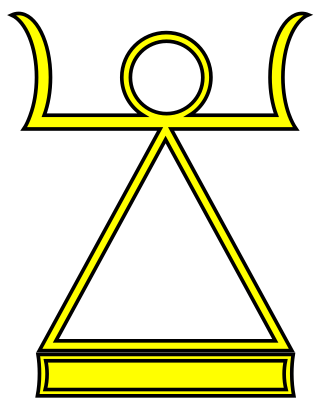

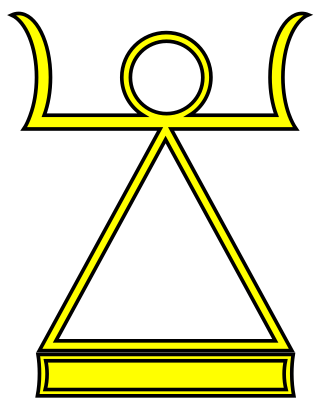

The sign of Tanit or sign of Tinnit is an anthropomorph symbol of the Punic goddess Tanit, present on many archaeological remains of the Carthaginian civilization.

The Carthage Administration Inscription is an inscription in the Punic language, using the Phoenician alphabet, discovered on the archaeological site of Carthage in the 1960s and preserved in the National Museum of Carthage. It is known as KAI 303.