Film stock is an analog medium that is used for recording motion pictures or animation. It is recorded on by a movie camera, developed, edited, and projected onto a screen using a movie projector. It is a strip or sheet of transparent plastic film base coated on one side with a gelatin emulsion containing microscopically small light-sensitive silver halide crystals. The sizes and other characteristics of the crystals determine the sensitivity, contrast and resolution of the film. The emulsion will gradually darken if left exposed to light, but the process is too slow and incomplete to be of any practical use. Instead, a very short exposure to the image formed by a camera lens is used to produce only a very slight chemical change, proportional to the amount of light absorbed by each crystal. This creates an invisible latent image in the emulsion, which can be chemically developed into a visible photograph. In addition to visible light, all films are sensitive to X-rays and high-energy particles. Most are at least slightly sensitive to invisible ultraviolet (UV) light. Some special-purpose films are sensitive into the infrared (IR) region of the spectrum.

The following list comprises significant milestones in the development of photography technology.

Photographic paper is a paper coated with a light-sensitive chemical, used for making photographic prints. When photographic paper is exposed to light, it captures a latent image that is then developed to form a visible image; with most papers the image density from exposure can be sufficient to not require further development, aside from fixing and clearing, though latent exposure is also usually present. The light-sensitive layer of the paper is called the emulsion, and functions similarly to photographic film. The most common chemistry used is gelatin silver, but other alternatives have also been used.

Color photography is photography that uses media capable of capturing and reproducing colors. By contrast, black-and-white or gray-monochrome photography records only a single channel of luminance (brightness) and uses media capable only of showing shades of gray.

Photographic printing is the process of producing a final image on paper for viewing, using chemically sensitized paper. The paper is exposed to a photographic negative, a positive transparency , or a digital image file projected using an enlarger or digital exposure unit such as a LightJet or Minilab printer. Alternatively, the negative or transparency may be placed atop the paper and directly exposed, creating a contact print. Digital photographs are commonly printed on plain paper, for example by a color printer, but this is not considered "photographic printing".

C-41 is a chromogenic color print film developing process introduced by Kodak in 1972, superseding the C-22 process. C-41, also known as CN-16 by Fuji, CNK-4 by Konica, and AP-70 by AGFA, is the most popular film process in use, with most, if not all photofinishing labs devoting at least one machine to this development process.

A safelight is a light source suitable for use in a photographic darkroom. It provides illumination only from parts of the visible spectrum to which the photographic material in use is nearly, or completely insensitive.

In infrared photography, the photographic film or image sensor used is sensitive to infrared light. The part of the spectrum used is referred to as near-infrared to distinguish it from far-infrared, which is the domain of thermal imaging. Wavelengths used for photography range from about 700 nm to about 900 nm. Film is usually sensitive to visible light too, so an infrared-passing filter is used; this lets infrared (IR) light pass through to the camera, but blocks all or most of the visible light spectrum; these filters thus look black (opaque) or deep red.

A panchromatic emulsion is a type of photographic emulsion that is sensitive to all wavelengths of visible light, and produces a monochrome photograph—typically black and white. Most modern commercially available film is panchromatic, and the technology is usually contrasted with earlier methods that cannot register all wavelengths, especially orthochromatic film.

Actinism is the property of solar radiation that leads to the production of photochemical and photobiological effects. Actinism is derived from the Ancient Greek ἀκτίς, ἀκτῖνος. The word actinism is found, for example, in the terminology of imaging technology, medicine, and chemistry, and the concept of actinism is applied, for example, in chemical photography and X-ray imaging.

Technical Pan is an almost panchromatic black-and-white film that was produced by Kodak. While it can reproduce the visible light spectrum, it leans to the red, and so unfiltered outdoor shots render blues, most notably the sky, with additional darkening and reds with some lightening. It was generally used as a very slow film, rated at EI 25 or even 16, although it could be rated at up to EI 320 with a distinct loss of tonal range and a bunching of shadow and highlight detail. This film has unmatched fine grain, especially when rated at a low speed, and makes excellent enlargements while preserving fine details. Kodak stopped selling it in 2004. It has not been replaced by a film with its characteristics. Although some of its particularities were unique and no emulsion in actual production could replace it, its resolution capabilities were surpassed by another film by ADOX, CMS 20 II.

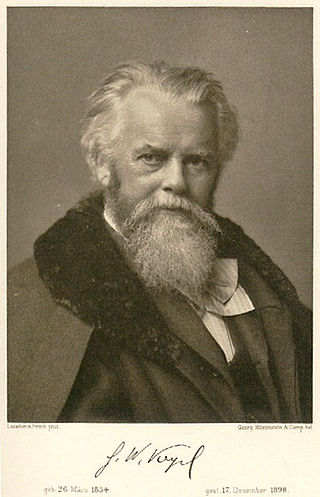

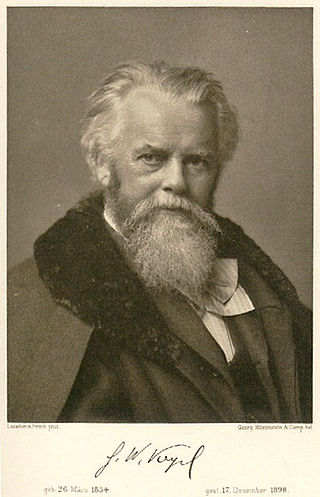

Hermann Wilhelm Vogel was a German photochemist and photographer who discovered dye sensitization, which is of great importance to photography.

Chromogenic photography is photography that works by a chromogen forming a conventional silver image and then replacing it with a dye image. Most films and papers used for color photography today are chromogenic, using three layers, each providing their own subtractive color. Some chromogenic films provide black-and-white negatives, and are processed in standard color developers. In this case, the dyes are a neutral color.

In cinematography, bipacking, or a bipack, is the process of loading two reels of film into a camera, so that they both pass through the camera gate together. It was used both for in-camera effects and as an early subtractive colour process.

Color motion picture film refers both to unexposed color photographic film in a format suitable for use in a motion picture camera, and to finished motion picture film, ready for use in a projector, which bears images in color.

Photographic emulsion is a light-sensitive colloid used in film-based photography. Most commonly, in silver-gelatin photography, it consists of silver halide crystals dispersed in gelatin. The emulsion is usually coated onto a substrate of glass, films, paper, or fabric. The substrate is often flexible and known as a film base.

Dye transfer is a continuous-tone color photographic printing process. It was used to print Technicolor films, as well as to produce paper colour prints used in advertising, or large transparencies for display.

In bipack color photography for motion pictures, two strips of black-and-white 35 mm film, running through the camera emulsion to emulsion, are used to record two regions of the color spectrum, for the purpose of ultimately printing the images, in complementary colors, superimposed on one strip of film. The result is a multicolored projection print that reproduces a useful but limited range of color by the subtractive color method. Bipack processes became commercially practical in the early 1910s when Kodak introduced duplitized film print stock, which facilitated making two-color prints.

Full-spectrum photography is a subset of multispectral imaging, defined among photography enthusiasts as imaging with consumer cameras the full, broad spectrum of a film or camera sensor bandwidth. In practice, specialized broadband/full-spectrum film captures visible and near infrared light, commonly referred to as the "VNIR".

Photographic film is a strip or sheet of transparent film base coated on one side with a gelatin emulsion containing microscopically small light-sensitive silver halide crystals. The sizes and other characteristics of the crystals determine the sensitivity, contrast, and resolution of the film. Film is typically segmented in frames, that give rise to separate photographs.