The Haber process, also called the Haber–Bosch process, is the main industrial procedure for the production of ammonia. The German chemists Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch developed it in the first decade of the 20th century. The process converts atmospheric nitrogen (N2) to ammonia (NH3) by a reaction with hydrogen (H2) using an iron metal catalyst under high temperatures and pressures. This reaction is slightly exothermic (i.e. it releases energy), meaning that the reaction is favoured at lower temperatures and higher pressures. It decreases entropy, complicating the process. Hydrogen is produced via steam reforming, followed by an iterative closed cycle to react hydrogen with nitrogen to produce ammonia.

Syngas, or synthesis gas, is a mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide, in various ratios. The gas often contains some carbon dioxide and methane. It is principally used for producing ammonia or methanol. Syngas is combustible and can be used as a fuel. Historically, it has been used as a replacement for gasoline, when gasoline supply has been limited; for example, wood gas was used to power cars in Europe during WWII.

A reducing atmosphere is an atmospheric condition in which oxidation is prevented by absence of oxygen and other oxidizing gases or vapours, and which may contain actively reductant gases such as hydrogen, carbon monoxide, methane and hydrogen sulfide that would be readily oxidized to remove any free oxygen. Although Early Earth had had a reducing prebiotic atmosphere prior to the Proterozoic eon, starting at about 2.5 billion years ago in the late Neoarchaean period, the Earth's atmosphere experienced a significant rise in oxygen transitioned to an oxidizing atmosphere with a surplus of molecular oxygen (dioxygen, O2) as the primary oxidizing agent.

Industrial processes are procedures involving chemical, physical, electrical, or mechanical steps to aid in the manufacturing of an item or items, usually carried out on a very large scale. Industrial processes are the key components of heavy industry.

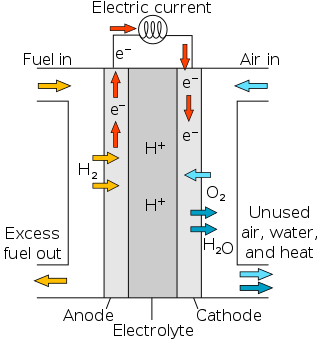

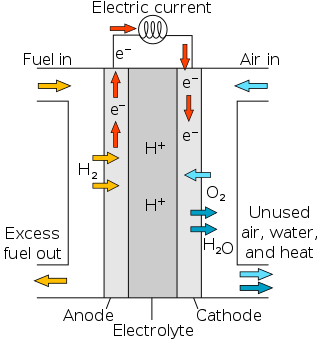

Proton-exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFC), also known as polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) fuel cells, are a type of fuel cell being developed mainly for transport applications, as well as for stationary fuel-cell applications and portable fuel-cell applications. Their distinguishing features include lower temperature/pressure ranges and a special proton-conducting polymer electrolyte membrane. PEMFCs generate electricity and operate on the opposite principle to PEM electrolysis, which consumes electricity. They are a leading candidate to replace the aging alkaline fuel-cell technology, which was used in the Space Shuttle.

Direct-methanol fuel cells or DMFCs are a subcategory of proton-exchange fuel cells in which methanol is used as the fuel. Their main advantage is the ease of transport of methanol, an energy-dense yet reasonably stable liquid at all environmental conditions.

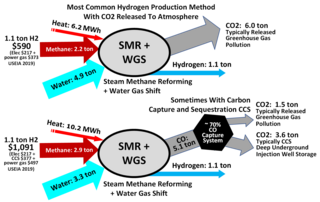

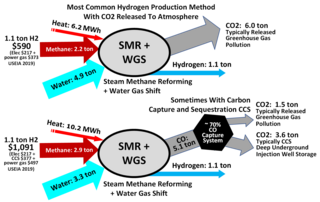

Steam reforming or steam methane reforming (SMR) is a method for producing syngas (hydrogen and carbon monoxide) by reaction of hydrocarbons with water. Commonly natural gas is the feedstock. The main purpose of this technology is hydrogen production. The reaction is represented by this equilibrium:

The Sabatier reaction or Sabatier process produces methane and water from a reaction of hydrogen with carbon dioxide at elevated temperatures and pressures in the presence of a nickel catalyst. It was discovered by the French chemists Paul Sabatier and Jean-Baptiste Senderens in 1897. Optionally, ruthenium on alumina makes a more efficient catalyst. It is described by the following exothermic reaction:

The water–gas shift reaction (WGSR) describes the reaction of carbon monoxide and water vapor to form carbon dioxide and hydrogen:

Water gas is a kind of fuel gas, a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen. It is produced by "alternately hot blowing a fuel layer [coke] with air and gasifying it with steam". The caloric yield of this is about 10% of a modern syngas plant. Further making this technology unattractive, its precursor coke is expensive, whereas syngas uses cheaper precursor, mainly methane from natural gas.

Hydrogen gas is produced by several industrial methods. Fossil fuels are the dominant source of hydrogen. As of 2020, the majority of hydrogen (~95%) is produced by steam reforming of natural gas and other light hydrocarbons, and partial oxidation of heavier hydrocarbons. Other methods of hydrogen production include biomass gasification and methane pyrolysis. Methane pyrolysis and water electrolysis can use any source of electricity including renewable energy.

A methane reformer is a device based on steam reforming, autothermal reforming or partial oxidation and is a type of chemical synthesis which can produce pure hydrogen gas from methane using a catalyst. There are multiple types of reformers in development but the most common in industry are autothermal reforming (ATR) and steam methane reforming (SMR). Most methods work by exposing methane to a catalyst at high temperature and pressure.

Partial oxidation (POX) is a type of chemical reaction. It occurs when a substoichiometric fuel-air mixture is partially combusted in a reformer, creating a hydrogen-rich syngas which can then be put to further use, for example in a fuel cell. A distinction is made between thermal partial oxidation (TPOX) and catalytic partial oxidation (CPOX).

Methanation is the conversion of carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide (COx) to methane (CH4) through hydrogenation. The methanation reactions of COx were first discovered by Sabatier and Senderens in 1902.

The Glossary of fuel cell terms lists the definitions of many terms used within the fuel cell industry. The terms in this fuel cell glossary may be used by fuel cell industry associations, in education material and fuel cell codes and standards to name but a few.

Reactive flash volatilization (RFV) is a chemical process that rapidly converts nonvolatile solids and liquids to volatile compounds by thermal decomposition for integration with catalytic chemistries.

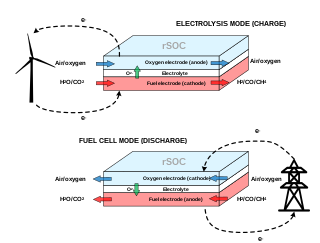

A solid oxide electrolyzer cell (SOEC) is a solid oxide fuel cell that runs in regenerative mode to achieve the electrolysis of water by using a solid oxide, or ceramic, electrolyte to produce hydrogen gas and oxygen. The production of pure hydrogen is compelling because it is a clean fuel that can be stored, making it a potential alternative to batteries, methane, and other energy sources. Electrolysis is currently the most promising method of hydrogen production from water due to high efficiency of conversion and relatively low required energy input when compared to thermochemical and photocatalytic methods.

Carbon dioxide reforming is a method of producing synthesis gas from the reaction of carbon dioxide with hydrocarbons such as methane with the aid of noble metal catalysts. Synthesis gas is conventionally produced via the steam reforming reaction or coal gasification. In recent years, increased concerns on the contribution of greenhouse gases to global warming have increased interest in the replacement of steam as reactant with carbon dioxide.

The first time a catalyst was used in the industry was in 1746 by J. Roebuck in the manufacture of lead chamber sulfuric acid. Since then catalysts have been in use in a large portion of the chemical industry. In the start only pure components were used as catalysts, but after the year 1900 multicomponent catalysts were studied and are now commonly used in the industry.

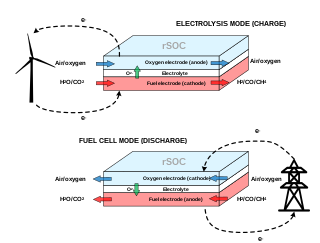

A reversible solid oxide cell (rSOC) is a solid-state electrochemical device that is operated alternatively as a solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC) and a solid oxide electrolysis cell (SOEC). Similarly to SOFCs, rSOCs are made of a dense electrolyte sandwiched between two porous electrodes. Their operating temperature ranges from 600°C to 900°C, hence they benefit from enhanced kinetics of the reactions and increased efficiency with respect to low-temperature electrochemical technologies.