Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau was a noted French Orientalist and archaeologist.

Bodashtart was a Phoenician ruler, who reigned as King of Sidon, the grandson of King Eshmunazar I, and a vassal of the Achaemenid Empire. He succeeded his cousin Eshmunazar II to the throne of Sidon, and scholars believe that he was succeeded by his son and proclaimed heir Yatonmilk.

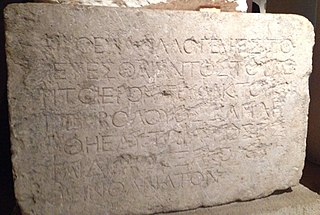

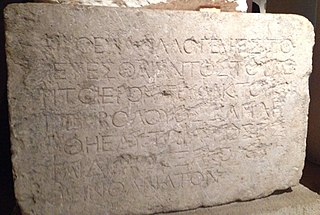

The Temple Warning inscription, also known as the Temple Balustrade inscription or the Soreg inscription, is an inscription that hung along the balustrade outside the Sanctuary of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Two of these tablets have been found. The inscription was a warning to pagan visitors to the temple not to proceed further. Both Greek and Latin inscriptions on the temple's balustrade served as warnings to pagan visitors not to proceed under penalty of death.

Umm Al Amad, or Umm el 'Amed or al Auamid or el-Awamid, is an Hellenistic period archaeological site near the town of Naqoura in Lebanon. It was discovered by Europeans in the 1770s, and was excavated in 1861. It is one of the most excavated archaeological sites in the Phoenician heartland.

The Baal Lebanon inscription, known as KAI 31, is a Phoenician inscription found in Limassol, Cyprus in eight bronze fragments in the 1870s. At the time of their discovery, they were considered to be the second most important finds in Semitic palaeography after the Mesha stele.

The Thrones of Astarte are approximately a dozen ex-voto "cherubim" thrones found in ancient Phoenician temples in Lebanon, in particular in areas around Sidon, Tyre and Umm al-Amad. Many of the thrones are similarly styled, flanked by cherubim-headed winged lions on either side. Images of the thrones are found in Phoenician sites around the Mediterranean, including an ivory plaque from Tel Megiddo (Israel), a relief from Hadrumetum (Tunisia) and a scarab from Tharros (Italy).

The Yehawmilk stele, de Clercq stele, or Byblos stele, also known as KAI 10 and CIS I 1, is a Phoenician inscription from c.450 BC found in Byblos at the end of Ernest Renan's Mission de Phénicie. Yehawmilk, king of Byblos, dedicated the stele to the city’s protective goddess Ba'alat Gebal.

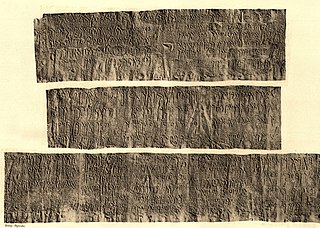

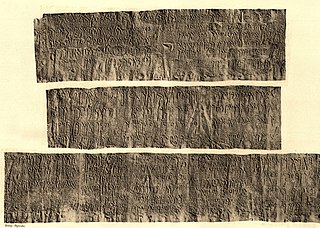

The Neirab steles are two 8th-century BC steles with Aramaic inscriptions found in 1891 in Al-Nayrab near Aleppo, Syria. They are currently in the Louvre. They were discovered in 1891 and acquired by Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau for the Louvre on behalf of the Commission of the Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum. The steles are made of black basalt, and the inscriptions note that they were funerary steles. The inscriptions are known as KAI 225 and KAI 226.

The Maktar and Mididi inscriptions are a number of Punic language inscriptions, found in the 1890s at Maktar and Mididi, Tunisia. A number of the most notable inscriptions have been collected in Kanaanäische und Aramäische Inschriften, and are known as are known as KAI 145-158.

The Abydos graffiti is Phoenician and Aramaic graffiti found on the walls of the Temple of Seti I at Abydos, Egypt. The inscriptions are known as KAI 49, CIS I 99-110 and RES 1302ff.

The Cirta steles are almost 1,000 Punic funerary and votive steles found in Cirta in a cemetery located on a hill immediately south of the Salah Bey Viaduct.

The Abdmiskar cippus is a white marble cippus in obelisk form discovered in Sidon, Lebanon, dated to 300 BCE. Discovered in 1890 by Joseph-Ange Durighello.

The Umm Al-Amad votive inscription is an ex-voto Phoenician inscription of two lines. Discovered during Ernest Renan's Mission de Phénicie in 1860–61, it was the second-longest of the three inscriptions found at Umm al-Amad. All three inscriptions were found on the north side of the hill.

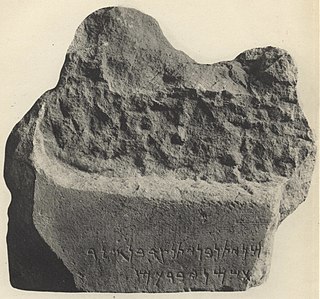

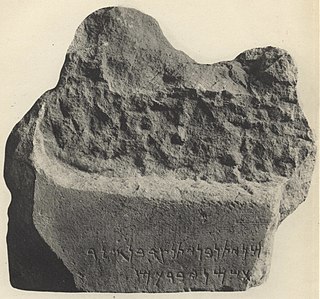

The Baalshamem inscription is a Phoenician inscription discovered in 1860–61 at Umm al-Amad, Lebanon, the longest of three inscriptions found there during Ernest Renan's Mission de Phénicie. All three inscriptions were found on the north side of the hill; this inscription was found in the foundation of one of the ruined houses covering the hill.

The Eshmun inscription is a Phoenician inscription on a fragment of grey-blue limestone found at the Temple of Eshmun in 1901. It is also known as RES 297. Some elements of the writing have been said to be similar to the Athenian Greek-Phoenician inscriptions. Today, it is held in the Museum of the Ancient Orient in Istanbul.

The Banobal stele is a Horus on the Crocodiles stele with a Phoenician graffiti inscription on a block of marble which served as a base for an Egyptian stele, found near the Pyramid of Unas in Memphis, Egypt in 1900. The inscription is known as KAI 48 or RES 1.

The Ain Nechma inscriptions, also known as the Guelma inscriptions are a number of Punic language inscriptions, first found in 1837 in the necropolis of Ain Nechma, in the Guelma Province of Algeria.

The Pierides Kition inscriptions are seven Phoenician inscriptions found in Kition by Demetrios Pierides in 1881 and acquired by the Louvre in 1885.

The Aadloun stele is a rock relief stele and inscription carved into the limestone rocks around the town of Aadloun in Lebanon, between Sidon and Tyre. Although heavily weathered when discovered in 1843, it was attributed to Ramesses II. It has been compared to the Stelae of Nahr el-Kalb approximately 60km to the north.

The Madaba Nabataean inscriptions are a pair of identical ancient texts carved in the Nabataean alphabet, discovered in the town of Madaba, Jordan. Dating to 37/38 CE during the reign of King Aretas IV, these inscriptions provide insight into the Nabataean civilization, particularly its language, administration, and funerary practices.