Related Research Articles

Taksony was the Grand Prince of the Hungarians after their catastrophic defeat in the 955 Battle of Lechfeld. In his youth he had participated in plundering raids in Western Europe, but during his reign the Hungarians only targeted the Byzantine Empire. The Gesta Hungarorum recounts that significant Muslim and Pecheneg groups settled in Hungary under Taksony.

Béla III was King of Hungary and Croatia between 1172 and 1196. He was the second son of King Géza II and Géza's wife, Euphrosyne of Kiev. Around 1161, Géza granted Béla a duchy, which included Croatia, central Dalmatia and possibly Sirmium. In accordance with a peace treaty between his elder brother, Stephen III, who succeeded their father in 1162, and the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos, Béla moved to Constantinople in 1163. He was renamed to Alexios, and the emperor granted him the newly created senior court title of despotes. He was betrothed to the Emperor's daughter, Maria. Béla's patrimony caused armed conflicts between the Byzantine Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary between 1164 and 1167, because Stephen III attempted to hinder the Byzantines from taking control of Croatia, Dalmatia and Sirmium. Béla-Alexios, who was designated as Emperor Manuel's heir in 1165, took part in three Byzantine campaigns against Hungary. His betrothal to the emperor's daughter was dissolved after her brother, Alexios, was born in 1169. The emperor deprived Béla of his high title, granting him the inferior rank of kaisar.

The Hungarian nobility consisted of a privileged group of individuals, most of whom owned landed property, in the Kingdom of Hungary. Initially, a diverse body of people were described as noblemen, but from the late 12th century only high-ranking royal officials were regarded as noble. Most aristocrats claimed a late 9th century Magyar leader for their ancestor. Others were descended from foreign knights, and local Slavic chiefs were also integrated in the nobility. Less illustrious individuals, known as castle warriors, also held landed property and served in the royal army. From the 1170s, most privileged laymen called themselves royal servants to emphasize their direct connection to the monarchs. The Golden Bull of 1222 enacted their liberties, especially their tax-exemption and the limitation of their military obligations. From the 1220s, royal servants were associated with the nobility and the highest-ranking officials were known as barons of the realm. Only those who owned allods – lands free of obligations – were regarded as true noblemen, but other privileged groups of landowners, known as conditional nobles, also existed.

Gesta Hungarorum, or The Deeds of the Hungarians, is the first extant Hungarian book about history. Its genre is not chronicle, but gesta, meaning "deeds" or "acts", which is a medieval entertaining literature. It was written by an unidentified author who has traditionally been called Anonymus in scholarly works. According to most historians, the work was completed between around 1200 and 1230. The Gesta exists in a sole manuscript from the second part of the 13th century, which was for centuries held in Vienna. It is part of the collection of Széchényi National Library in Budapest.

The ispán or count was the leader of a castle district in the Kingdom of Hungary from the early 11th century. Most of them were also heads of the basic administrative units of the kingdom, called counties, and from the 13th century the latter function became dominant. The ispáns were appointed and dismissed by either the monarchs or a high-ranking royal official responsible for the administration of a larger territorial unit within the kingdom. They fulfilled administrative, judicial and military functions in one or more counties.

Csanád, also Chanadinus, or Cenad, was the first head (comes) of Csanád County in the Kingdom of Hungary in the first decades of the 11th century.

Anonymus Bele regis notarius or Master P. was the notary and chronicler of a Hungarian king, probably Béla III. Little is known about him, but his latinized name began with P, as he referred to himself as "P. dictus magister".

A castle warrior or castle serf was a landholder obliged to provide military services to the ispán or head of a royal castle district in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. Castle warriors "formed a privileged, elite class that ruled over the mass of castle folk" from the establishment of the kingdom around 1000 AD. Due to the disintegration of the system of castle districts, many castle warriors became serfs working on the lands of private landholders in the 13th and 14th centuries; however, some of them were granted a full or "conditional noble" status.

A conditional noble or predialist was a landowner in the Kingdom of Hungary who was obliged to render specific services to his lord in return for his landholding, in contrast with a "true nobleman of the realm" who held his estates free of such services. Most conditional nobles lived in the border territories of the kingdom, including Slavonia and Transylvania, but some of their groups possessed lands in estates of Roman Catholic prelates. Certain groups of conditional nobility, including the "ecclesiastic nobles" and the "nobles of Turopolje" preserved their specific status until the 19th century.

A perpetual count was a head or an ispán of a county in the Kingdom of Hungary whose office was either hereditary or attached to the dignity of a prelate or of a great officer of the realm. The earliest examples of a perpetual ispánate are from the 12th century, but the institution flourished between the 15th and 18th centuries. Although all administrative functions of the office were abolished in 1870, the title itself was preserved until the general abolition of noble titles in Hungary in 1946.

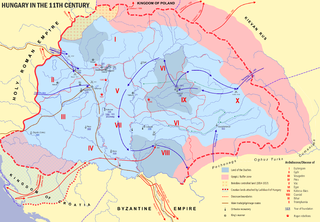

The Kingdom of Hungary came into existence in Central Europe when Stephen I, Grand Prince of the Hungarians, was crowned king in 1000 or 1001. He reinforced central authority and forced his subjects to accept Christianity. Although all written sources emphasize only the role played by German and Italian knights and clerics in the process, a significant part of the Hungarian vocabulary for agriculture, religion and state was taken from Slavic languages. Civil wars and pagan uprisings, along with attempts by the Holy Roman Emperors to expand their authority over Hungary, jeopardized the new monarchy. The monarchy stabilized during the reigns of Ladislaus I (1077–1095) and Coloman (1095–1116). These rulers occupied Croatia and Dalmatia with the support of a part of the local population. Both realms retained their autonomous position. The successors of Ladislaus and Coloman—especially Béla II (1131–1141), Béla III (1176–1196), Andrew II (1205–1235), and Béla IV (1235–1270)—continued this policy of expansion towards the Balkan Peninsula and the lands east of the Carpathian Mountains, transforming their kingdom into one of the major powers of medieval Europe.

The ten-lanced nobles, also Szepes lancers,Spiš lancers, or lance-bearers of Szepes were group of conditional noblemen living in the Szepes region of the Kingdom of Hungary. These nobles were previously part of the contingent assigned with border guard duties in the periphery of the conquered territories in the region. In the thirteenth century, some of these groups were officially integrated into the Hungarian nobility. They received their privileges from King Béla IV of Hungary in 1243. They were obliged to equip ten knights or lancers. They were not subject to the authority of the ispán of Szepes County and tax was collected from them only if the "royal servants" were also required to pay it. Initially, they formed about 40 families, but their number decreased to less than 20 families by the 16th century. They lost their special status in 1804.

The udvornici, also udvarniks or royal serving people, was a class of half-free people who were obliged to provide well-specified services to the royal court in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. They seem to have been descended from the Slavic population which was subjugated during the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin. Word udvornici is derived from slavic "U dvora", meaning "at/near the (royal) court". Their lord was the monarch, but they were administered by the Palatine.

The castle folk formed a class of freemen who were obliged to provide well-specified services to a royal castle and its ispán, or count, in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. They were peasants living in villages formed in the lands pertaining to the royal castle. They tilled their estates collectively.

Prefection, also promotion of a daughter to a son, was a royal prerogative in the Kingdom of Hungary, whereby the sovereign granted the status of a son to a nobleman's daughter, authorizing her to inherit her father's landed property and transmitting noble status to her children even if she married a commoner. Such a daughter was called a praefecta in Latin.

Regestrum Varadinense, or Oradea Register, is a document which preserved the minutes of hundreds of trials by ordeal. The ordeals were held under the auspices of the canons of the cathedral chapter of Várad in the first decades of the 12th century. It is "one of the most remarkable documents of social history in medieval Transylvania", according to historian Florin Curta.

Scholarly theories about the origin of the Székelys can be divided into four main groups. Medieval chronicles unanimously stated that the Székelys were descended from the Huns and settled in the Carpathian Basin centuries before the Hungarians conquered the territory in the late 9th century. This theory is refuted by most modern specialists. According to a widely accepted modern hypothesis, the Székelys were originally a Turkic people who joined the Magyars in the Pontic steppes. Another well-known theory states that the Székelys are simply Magyars, descended from the border guards of the Kingdom of Hungary who settled in the easternmost region of the Carpathian Basin and preserved their special privileges for centuries. According to a fourth theory, the Székelys' origin can be traced back to the Late Avar population of the Carpathian Basin.

The daughters' quarter, also known as filial quarter, was the legal doctrine that regulated the right of a Hungarian nobleman's daughter to inherit her father's property.

The banderium was a military unit which was distinguished by the banner of a high-ranking clergyman or nobleman in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. Its name derived from the Latin or Italian words for banner.

The militia portalis, also known as peasant militia, was the first institution that secured the peasants' permanent participation in the defence of the Kingdom of Hungary. It was established when the Diet of Hungary obliged all landowners to equip one archer for 20 peasant plots on their estates to serve in the royal army in 1397. The unprofessional soldiers were to serve in the militia only during the emergency period.

References

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 122.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 70.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 123.