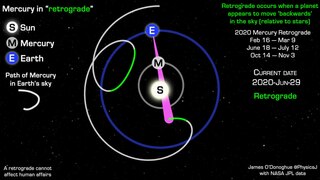

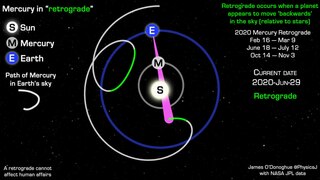

Apparent retrograde motion is the apparent motion of a planet in a direction opposite to that of other bodies within its system, as observed from a particular vantage point. Direct motion or prograde motion is motion in the same direction as other bodies.

Aristarchus of Samos was an ancient Greek astronomer and mathematician who presented the first known heliocentric model that placed the Sun at the center of the universe, with the Earth revolving around the Sun once a year and rotating about its axis once a day. He supported the theory of Anaxagoras according to which the Sun was just another star.

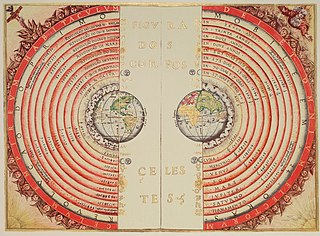

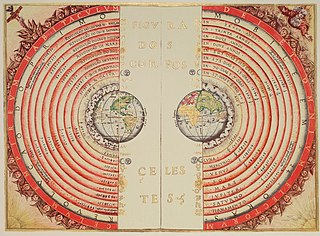

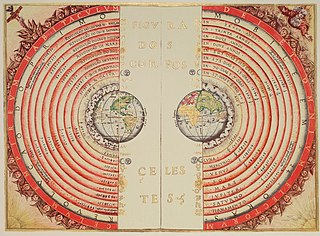

In astronomy, the geocentric model is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets all orbit Earth. The geocentric model was the predominant description of the cosmos in many European ancient civilizations, such as those of Aristotle in Classical Greece and Ptolemy in Roman Egypt, as well as during the Islamic Golden Age.

In the Hipparchian, Ptolemaic, and Copernican systems of astronomy, the epicycle was a geometric model used to explain the variations in speed and direction of the apparent motion of the Moon, Sun, and planets. In particular it explained the apparent retrograde motion of the five planets known at the time. Secondarily, it also explained changes in the apparent distances of the planets from the Earth.

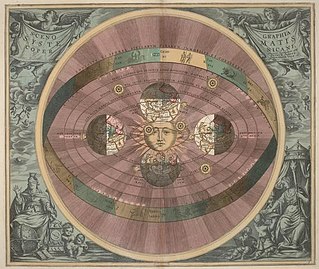

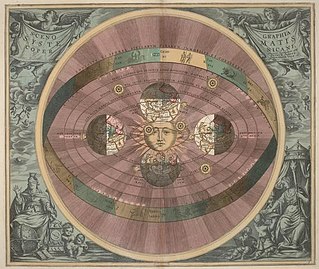

Heliocentrism is a superseded astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the centre of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at the center. The notion that the Earth revolves around the Sun had been proposed as early as the 3rd century BC by Aristarchus of Samos, who had been influenced by a concept presented by Philolaus of Croton. In the 5th century BC the Greek philosophers Philolaus and Hicetas had the thought on different occasions that the Earth was spherical and revolving around a "mystical" central fire, and that this fire regulated the universe. In medieval Europe, however, Aristarchus' heliocentrism attracted little attention—possibly because of the loss of scientific works of the Hellenistic period.

The Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems is a 1632 Italian-language book by Galileo Galilei comparing the Copernican system with the traditional Ptolemaic system. It was translated into Latin as Systema cosmicum in 1635 by Matthias Bernegger. The book was dedicated to Galileo's patron, Ferdinando II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, who received the first printed copy on February 22, 1632.

The Tychonic system is a model of the universe published by Tycho Brahe in 1588, which combines what he saw as the mathematical benefits of the Copernican system with the philosophical and "physical" benefits of the Ptolemaic system. The model may have been inspired by Valentin Naboth and Paul Wittich, a Silesian mathematician and astronomer. A similar cosmological model was independently proposed in the Hindu astronomical treatise Tantrasamgraha by Nilakantha Somayaji of the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics.

Nicolaus Copernicus was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulated a model of the universe that placed the Sun rather than Earth at its center. In all likelihood, Copernicus developed his model independently of Aristarchus of Samos, an ancient Greek astronomer who had formulated such a model some eighteen centuries earlier.

The celestial spheres, or celestial orbs, were the fundamental entities of the cosmological models developed by Plato, Eudoxus, Aristotle, Ptolemy, Copernicus, and others. In these celestial models, the apparent motions of the fixed stars and planets are accounted for by treating them as embedded in rotating spheres made of an aetherial, transparent fifth element (quintessence), like gems set in orbs. Since it was believed that the fixed stars did not change their positions relative to one another, it was argued that they must be on the surface of a single starry sphere.

In astronomy, the fixed stars are the luminary points, mainly stars, that appear not to move relative to one another against the darkness of the night sky in the background. This is in contrast to those lights visible to naked eye, namely planets and comets, that appear to move slowly among those "fixed" stars. The fixed stars includes all the stars visible to the naked eye other than the Sun, as well as the faint band of the Milky Way. Due to their star-like appearance when viewed with the naked eye, the few visible individual nebulae and other deep-sky objects also are counted among the fixed stars. Approximately 6,000 stars are visible to the naked eye under optimal conditions.

Giovanni Battista Riccioli, SJ was an Italian astronomer and a Catholic priest in the Jesuit order. He is known, among other things, for his experiments with pendulums and with falling bodies, for his discussion of 126 arguments concerning the motion of the Earth, and for introducing the current scheme of lunar nomenclature. He is also widely known for discovering the first double star. He argued that the rotation of the Earth should reveal itself because on a rotating Earth, the ground moves at different speeds at different times.

De revolutionibus orbium coelestium is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book, first printed in 1543 in Nuremberg, Holy Roman Empire, offered an alternative model of the universe to Ptolemy's geocentric system, which had been widely accepted since ancient times.

The Copernican Revolution was the paradigm shift from the Ptolemaic model of the heavens, which described the cosmos as having Earth stationary at the center of the universe, to the heliocentric model with the Sun at the center of the Solar System. This revolution consisted of two phases; the first being extremely mathematical in nature and the second phase starting in 1610 with the publication of a pamphlet by Galileo. Beginning with the 1543 publication of Nicolaus Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, contributions to the “revolution” continued until finally ending with Isaac Newton’s work over a century later.

Ancient Greek astronomy is the astronomy written in the Greek language during classical antiquity. Greek astronomy is understood to include the Ancient Greek, Hellenistic, Greco-Roman, and late antique eras. Ancient Greek astronomy can be divided into three primary phases: Classical Greek Astronomy, which encompassed the 5th and 4th centuries BC, and Hellenistic Astronomy, which encompasses the subsequent period until the formation of the Roman Empire ca. 30 BC, and finally Greco-Roman astronomy, which refers to the continuation of the tradition of Greek astronomy in the Roman world. During the Hellenistic era and onwards, Greek astronomy expanded beyond the geographic region of Greece as the Greek language had become the language of scholarship throughout the Hellenistic world, in large part delimited by the boundaries of the Macedonian Empire established by Alexander the Great. The most prominent and influential practitioner of Greek astronomy was Ptolemy, whose treatise Almagest shaped astronomical thinking until the modern era. Most of the most prominent constellations known today are taken from Greek astronomy, albeit via the terminology they took on in Latin.

Earth's rotation or Earth's spin is the rotation of planet Earth around its own axis, as well as changes in the orientation of the rotation axis in space. Earth rotates eastward, in prograde motion. As viewed from the northern polar star Polaris, Earth turns counterclockwise.

Islamic cosmology is the cosmology of Islamic societies. Islamic cosmology is not a single unitary system, but is inclusive of a number of cosmological systems, including Quranic cosmology, the cosmology of the Hadith collections, as well as those of Islamic astronomy and astrology. Broadly, cosmological conceptions themselves can be divided into thought concerning the physical structure of the cosmos (cosmography) and the origins of the cosmos (cosmogony).

Copernican heliocentrism is the astronomical model developed by Nicolaus Copernicus and published in 1543. This model positioned the Sun at the center of the Universe, motionless, with Earth and the other planets orbiting around it in circular paths, modified by epicycles, and at uniform speeds. The Copernican model displaced the geocentric model of Ptolemy that had prevailed for centuries, which had placed Earth at the center of the Universe.

The center of the Universe is a concept that lacks a coherent definition in modern astronomy; according to standard cosmological theories on the shape of the universe, it has no distinct spatial center.

Jacques du Chevreul was a French mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher.

Historical models of the Solar System first appeared during prehistoric periods and remain updated to this day.. The models of the Solar System throughout history were first represented in the early form of cave markings and drawings, calendars and astronomical symbols. Then books and written records became the main source of information that expressed the way the people of the time thought of the Solar System.