| Provincial Court Judges' Assn of New Brunswick v New Brunswick (Minister of Justice) | |

|---|---|

| Hearing: November 9–10, 2004 Judgment: Decided July 22, 2005 | |

| Full case name | Provincial Court Judges’ Association of New Brunswick, Honourable Judge Michael McKee and Honourable Judge Steven Hutchinson v Her Majesty The Queen in Right of the Province of New Brunswick, as represented by the Minister of Justice |

| Citations | [2005] 2 S.C.R. 286; 2005 SCC 44 (CanLII); (2005), 288 N.B.R. (2d) 202; (2005), 255 D.L.R. (4th) 513; (2005), 30 Admin. L.R. (4th) 1; (2005), 201 O.A.C. 293 |

| Docket No. | 30006 |

| Prior history | Judgment for the Crown in the Court of Appeal for New Brunswick. |

| Holding | |

| The reasons given by the governments of Alberta, Ontario and New Brunswick for not following judicial remuneration recommendations were rational. | |

| Court Membership | |

| Chief Justice: Beverley McLachlin Puisne Justices: John C. Major, Michel Bastarache, Ian Binnie, Louis LeBel, Marie Deschamps, Morris Fish, Rosalie Abella, Louise Charron | |

| Reasons given | |

| Unanimous reasons by | The Court |

Provincial Court Judges' Assn of New Brunswick v New Brunswick (Minister of Justice); Ontario Judges Assn v Ontario (Management Board); Bodner v Alberta; Conférence des juges du Québec v Quebec (AG); Minc v Quebec (AG) [2005] 2 S.C.R. 286 was a decision by the Supreme Court of Canada in which the Court attempted to resolve questions about judicial independence left over from the landmark Provincial Judges Reference (1997). The Court found that government remuneration of provincial court judges that is lower than what an independent salary commission recommended can be justified. A broader perspective should be taken whether overall conditions of judicial independence have been met and some deference to the government is needed.

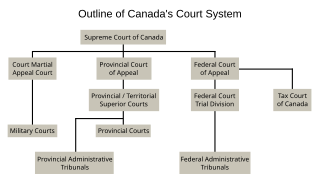

The Supreme Court of Canada is the highest court of Canada, the final court of appeals in the Canadian justice system. The court grants permission to between 40 and 75 litigants each year to appeal decisions rendered by provincial, territorial and federal appellate courts. Its decisions are the ultimate expression and application of Canadian law and binding upon all lower courts of Canada, except to the extent that they are overridden or otherwise made ineffective by an Act of Parliament or the Act of a provincial legislative assembly pursuant to section 33 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Judicial independence is the concept that the judiciary should be independent from the other branches of government. That is, courts should not be subject to improper influence from the other branches of government or from private or partisan interests. Judicial independence is important to the idea of separation of powers.

The Provincial Judges Reference [1997] 3 S.C.R. 3 is a leading opinion of the Supreme Court of Canada in response to a reference question regarding remuneration and the independence and impartiality of provincial court judges. Notably, the majority opinion found all judges are independent, not just superior court judges and inferior court judges concerned with criminal law, as the written constitution stipulates. Unwritten constitutional principles were relied upon to demonstrate this, indicating such principles were growing in importance in constitutional interpretation. The reference also remains one of the most definitive statements on the extent to which all judges in Canada are protected by the Constitution.