Anxiety is an emotion characterised by an unpleasant state of inner turmoil and includes feelings of dread over anticipated events. Anxiety is different from fear in that fear is defined as the emotional response to a present threat, whereas anxiety is the anticipation of a future one. It is often accompanied by nervous behavior such as pacing back and forth, somatic complaints, and rumination.

Endocrinology is a branch of biology and medicine dealing with the endocrine system, its diseases, and its specific secretions known as hormones. It is also concerned with the integration of developmental events proliferation, growth, and differentiation, and the psychological or behavioral activities of metabolism, growth and development, tissue function, sleep, digestion, respiration, excretion, mood, stress, lactation, movement, reproduction, and sensory perception caused by hormones. Specializations include behavioral endocrinology and comparative endocrinology.

The endocrine system is a messenger system in an organism comprising feedback loops of hormones that are released by internal glands directly into the circulatory system and that target and regulate distant organs. In vertebrates, the hypothalamus is the neural control center for all endocrine systems.

Gender dysphoria (GD) is the distress a person experiences due to a mismatch between their gender identity—their personal sense of their own gender—and their sex assigned at birth. The term replaced the previous diagnostic label of gender identity disorder (GID) in 2013 with the release of the diagnostic manual DSM-5. The condition was renamed to remove the stigma associated with the term disorder. The International Classification of Diseases uses the term gender incongruence instead of gender dysphoria, defined as a marked and persistent mismatch between gender identity and assigned gender, regardless of distress or impairment.

Psychopharmacology is the scientific study of the effects drugs have on mood, sensation, thinking, behavior, judgment and evaluation, and memory. It is distinguished from neuropsychopharmacology, which emphasizes the correlation between drug-induced changes in the functioning of cells in the nervous system and changes in consciousness and behavior.

Stress, whether physiological, biological or psychological, is an organism's response to a stressor such as an environmental condition. When stressed by stimuli that alter an organism's environment, multiple systems respond across the body. In humans and most mammals, the autonomic nervous system and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis are the two major systems that respond to stress. Two well-known hormones that humans produce during stressful situations are adrenaline and cortisol.

Delayed puberty is when a person lacks or has incomplete development of specific sexual characteristics past the usual age of onset of puberty. The person may have no physical or hormonal signs that puberty has begun. In the United States, girls are considered to have delayed puberty if they lack breast development by age 13 or have not started menstruating by age 15. Boys are considered to have delayed puberty if they lack enlargement of the testicles by age 14. Delayed puberty affects about 2% of adolescents.

Psychoneuroimmunology (PNI), also referred to as psychoendoneuroimmunology (PENI) or psychoneuroendocrinoimmunology (PNEI), is the study of the interaction between psychological processes and the nervous and immune systems of the human body. It is a subfield of psychosomatic medicine. PNI takes an interdisciplinary approach, incorporating psychology, neuroscience, immunology, physiology, genetics, pharmacology, molecular biology, psychiatry, behavioral medicine, infectious diseases, endocrinology, and rheumatology.

Pituitary adenomas are tumors that occur in the pituitary gland. Most pituitary tumors are benign, approximately 35% are invasive and just 0.1% to 0.2% are carcinomas. Pituitary adenomas represent from 10% to 25% of all intracranial neoplasms, with an estimated prevalence rate in the general population of approximately 17%.

Kallmann syndrome (KS) is a genetic disorder that prevents a person from starting or fully completing puberty. Kallmann syndrome is a form of a group of conditions termed hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. To distinguish it from other forms of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, Kallmann syndrome has the additional symptom of a total lack of sense of smell (anosmia) or a reduced sense of smell. If left untreated, people will have poorly defined secondary sexual characteristics, show signs of hypogonadism, almost invariably are infertile and are at increased risk of developing osteoporosis. A range of other physical symptoms affecting the face, hands and skeletal system can also occur.

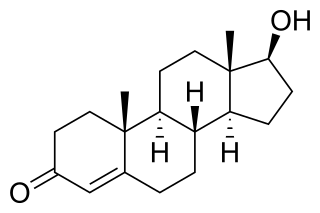

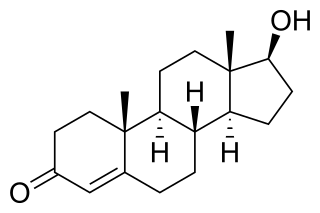

Hyperandrogenism is a medical condition characterized by high levels of androgens. It is more common in women than men. Symptoms of hyperandrogenism may include acne, seborrhea, hair loss on the scalp, increased body or facial hair, and infrequent or absent menstruation. Complications may include high blood cholesterol and diabetes. It occurs in approximately 5% of women of reproductive age.

False pregnancy is the appearance of clinical or subclinical signs and symptoms associated with pregnancy although the individual is not physically carrying a fetus. The mistaken impression that one is pregnant includes signs and symptoms such as tender breasts with secretions, abdominal growth, delayed menstrual periods, and subjective feelings of a moving fetus. Examination, ultrasound, and pregnancy tests can be used to rule out false pregnancy.

The hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis refers to the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and gonadal glands as if these individual endocrine glands were a single entity. Because these glands often act in concert, physiologists and endocrinologists find it convenient and descriptive to speak of them as a single system.

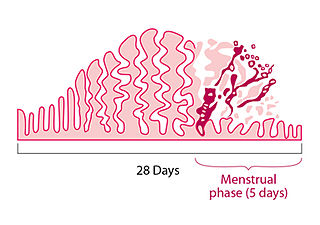

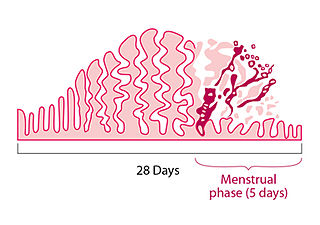

A menstrual disorder is characterized as any abnormal condition with regards to a woman's menstrual cycle. There are many different types of menstrual disorders that vary with signs and symptoms, including pain during menstruation, heavy bleeding, or absence of menstruation. Normal variations can occur in menstrual patterns but generally menstrual disorders can also include periods that come sooner than 21 days apart, more than 3 months apart, or last more than 10 days in duration. Variations of the menstrual cycle are mainly caused by the immaturity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis, and early detection and management is required in order to minimize the possibility of complications regarding future reproductive ability.

Euthyroid sick syndrome (ESS) is a state of adaptation or dysregulation of thyrotropic feedback control wherein the levels of T3 and/or T4 are abnormal, but the thyroid gland does not appear to be dysfunctional. This condition may result from allostatic responses of hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid feedback control, dyshomeostatic disorders, drug interferences, and impaired assay characteristics in critical illness.

The classification of mental disorders, also known as psychiatric nosology or psychiatric taxonomy, is central to the practice of psychiatry and other mental health professions.

Psychological dependence is a cognitive disorder and a form of dependence that is characterized by emotional–motivational withdrawal symptoms upon cessation of prolonged drug use or certain repetitive behaviors. Consistent and frequent exposure to particular substances or behaviors is responsible for inducing psychological dependence, requiring ongoing engagement to prevent the onset of an unpleasant withdrawal syndrome driven by negative reinforcement. Neuronal counter-adaptation is believed to contribute to the generation of withdrawal symptoms through changes in neurotransmitter activity or altered receptor expression. Environmental enrichment and physical activity have been shown to attenuate withdrawal symptoms.

Hypothalamic disease is a disorder presenting primarily in the hypothalamus, which may be caused by damage resulting from malnutrition, including anorexia and bulimia eating disorders, genetic disorders, radiation, surgery, head trauma, lesion, tumour or other physical injury to the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus is the control center for several endocrine functions. Endocrine systems controlled by the hypothalamus are regulated by antidiuretic hormone (ADH), corticotropin-releasing hormone, gonadotropin-releasing hormone, growth hormone-releasing hormone, oxytocin, all of which are secreted by the hypothalamus. Damage to the hypothalamus may impact any of these hormones and the related endocrine systems. Many of these hypothalamic hormones act on the pituitary gland. Hypothalamic disease therefore affects the functioning of the pituitary and the target organs controlled by the pituitary, including the adrenal glands, ovaries and testes, and the thyroid gland.

Fetal programming, also known as prenatal programming, is the theory that environmental cues experienced during fetal development play a seminal role in determining health trajectories across the lifespan.

Mini-puberty is a transient hormonal activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis that occurs in infants shortly after birth. This period is characterized by a surge in the secretion of gonadotropins and sex steroids, similar to but less intense than the hormonal changes that occur in puberty during adolescence. Mini-puberty plays a crucial role in the early development of the reproductive system and the establishment of secondary sexual characteristics.