A sex worker is a person who provides sex work, either on a regular or occasional basis. The term is used in reference to those who work in all areas of the sex industry.

Safe sex is sexual activity using methods or contraceptive devices to reduce the risk of transmitting or acquiring sexually transmitted infections (STIs), especially HIV. "Safe sex" is also sometimes referred to as safer sex or protected sex to indicate that some safe sex practices do not eliminate STI risks. It is also sometimes used colloquially to describe methods aimed at preventing pregnancy that may or may not also lower STI risks.

Sexual assault is an act in which one intentionally sexually touches another person without that person's consent, or coerces or physically forces a person to engage in a sexual act against their will. It is a form of sexual violence that includes child sexual abuse, groping, rape, drug facilitated sexual assault, and the torture of the person in a sexual manner.

Prison sexuality consists of sexual relationships between prisoners or between a prisoner and a prison employee or other persons to whom prisoners have access. Since prisons are usually separated by sex, most sexual activity is with a same-sex partner. Exceptions to this include sex with spouses/partners during conjugal visits and sex with a prison employee of the opposite sex.

Battery is a criminal offense involving unlawful physical contact, distinct from assault which is the act of creating apprehension of such contact.

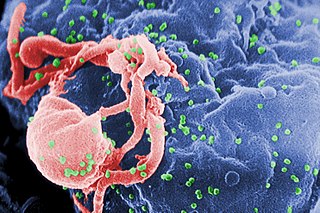

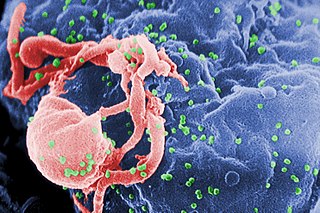

Criminal transmission of HIV is the intentional or reckless infection of a person with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). This is often conflated, in laws and in discussion, with criminal exposure to HIV, which does not require the transmission of the virus and often, as in the cases of spitting and biting, does not include a realistic means of transmission. Some countries or jurisdictions, including some areas of the U.S., have enacted laws expressly to criminalize HIV transmission or exposure, charging those accused with criminal transmission of HIV. Other countries charge the accused under existing laws with such crimes as murder, manslaughter, attempted murder, assault or fraud.

Bugchasing is the particularly rare practice of intentionally seeking human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection through sexual activity.

Bareback sex is physical sexual activity, especially sexual penetration, without the use of a condom. The topic primarily concerns anal sex between men without the use of a condom, and may be distinguished from unprotected sex because bareback sex denotes the deliberate act of forgoing condom use.

Johnson Aziga is a Ugandan-born Canadian man formerly residing in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, notable as the first person to be charged and convicted of first-degree murder in Canada for spreading HIV, after two women whom he had infected without their knowledge died.

Trevis Smith is a former football linebacker who played seven years with the Saskatchewan Roughriders of the Canadian Football League (CFL). Born in Montgomery, Alabama, Smith was formerly a linebacker for the University of Alabama.

In criminal law, consent may be used as an excuse and prevent the defendant from incurring liability for what was done.

The precise definitions of and punishments for aggravated sexual assault and aggravated rape vary from nation to nation and state to state within nations.

Serosorting, also known as serodiscrimination, is the practice of using HIV status as a decision-making point in choosing sexual behavior. The term is used to describe the behavior of a person who chooses a sexual partner assumed to be of the same HIV serostatus in order to engage in unprotected sex with them for a reduced risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV/AIDS.

Carl Desmond Leone is a Canadian businessman from Windsor, Ontario. Leone was jailed after pleading guilty in a Windsor court to 15 counts of aggravated sexual assault for not informing his sexual partners of his positive HIV status. It is believed he has been charged with exposing more women to the AIDS-causing virus than anyone in Canadian history. Two of his victims have attempted suicide.

Edgard Monge is a native of Nicaragua who is serving a ten-year sentence in Kingston Penitentiary, Ontario, Canada, for four counts of aggravated assault after he knowingly had unprotected sex while HIV infected and failed to inform his four sexual partners. Two of his partners also became infected with HIV. One of the two had a child from the union with Monge and the child also contracted HIV.

R v JA2011 SCC 28 is a criminal law decision of the Supreme Court of Canada regarding consent in cases of sexual assaults. The court found that a person can only consent to sexual activity if they are conscious throughout that activity. If a person becomes unconscious during the sexual activity, then they legally cannot consent, whether or not they consented earlier. In addition to the two parties, the Court heard from two interveners: the Attorney General of Canada and the Women's Legal Education and Action Fund (LEAF).

Since reports of emergence and spread of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the United States between the 1970s and 1980s, the HIV/AIDS epidemic has frequently been linked to gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) by epidemiologists and medical professionals. It was first noticed after doctors discovered clusters of Kaposi's sarcoma and pneumocystis pneumonia in homosexual men in Los Angeles, New York City, and San Francisco in 1981. The first official report on the virus was published by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) on June 5, 1981 and detailed the cases of five young gay men who were hospitalized with serious infections. A month later, The New York Times reported that 41 homosexuals had been diagnosed with Kaposi's sarcoma, and eight had died less than 24 months after the diagnosis was made.

The criminal transmission of HIV in the United States varies among jurisdictions. More than thirty of the fifty U.S. states have prosecuted HIV-positive individuals for exposing another person to HIV. State laws criminalize different behaviors and assign different penalties. While pinpointing who infected whom is scientifically impossible, a person diagnosed with HIV who is accused of infecting another while engaging in sexual intercourse is, in many jurisdictions, automatically committing a crime. A person donating HIV-infected organs, tissues, and blood can be prosecuted for transmitting the virus. Spitting or transmitting HIV-infected bodily fluids is a criminal offense in some states, particularly if the target is a prison guard. Some states treat the transmission of HIV, depending upon a variety of factors, as a felony and others as a misdemeanor.

Non-consensual condom removal, or "stealthing", is the practice of a person removing a condom during sexual intercourse without consent, when their sex partner has only consented to condom-protected sex. Victims are exposed to potential sexually transmitted diseasess (STDs) such as HIV/AIDS, or unwanted pregnancies. Such behaviour may be therefore regarded as sexual assault or rape, and sometimes as a form of reproductive coercion. As of 2020, stealthing is punishable as a form of sexual violence in some countries, such as Germany and the United Kingdom.

R v Hutchinson, 2014 SCC 19 is a decision of the Supreme Court of Canada on sexual assault and consent under the Criminal Code. The Court upheld the sexual assault conviction of a defendant in a condom sabotage case, holding that the complainant's consent to sexual activity with him had been vitiated by fraud when he poked holes in his condom.