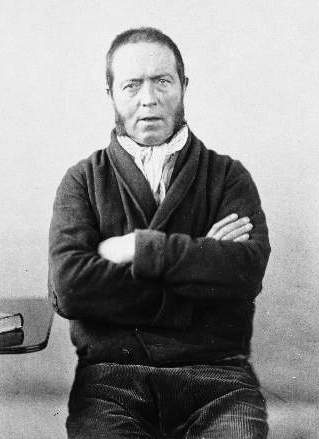

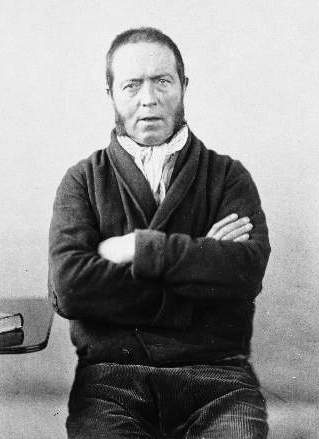

The M'Naghten rule(s) (pronounced, and sometimes spelled, McNaughton) is a legal test defining the defence of insanity, first formulated by House of Lords in 1843. It is the established standard in UK criminal law, and versions have also been adopted in some US states (currently or formerly), and other jurisdictions, either as case law or by statute. Its original wording is a proposed jury instruction:

that every man is to be presumed to be sane, and ... that to establish a defence on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.

In criminal law, mens rea is the mental state of a defendant who is accused of committing a crime. In common law jurisdictions, most crimes require proof both of mens rea and actus reus before the defendant can be found guilty.

The Protection of Children Act 1978 is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that criminalized indecent photographs of children. The act applies in England and Wales. Similar provision for Scotland is contained in the Civic Government (Scotland) Act 1982 and for Northern Ireland in the Protection of Children Order 1978.

An attempt to commit a crime occurs if a criminal has an intent to commit a crime and takes a substantial step toward completing the crime, but for reasons not intended by the criminal, the final resulting crime does not occur. Attempt to commit a particular crime is a crime, usually considered to be of the same or lesser gravity as the particular crime attempted. Attempt is a type of inchoate crime, a crime that is not fully developed. The crime of attempt has two elements, intent and some conduct toward completion of the crime.

In criminal law, automatism is a rarely used criminal defence. It is one of the mental condition defences that relate to the mental state of the defendant. Automatism can be seen variously as lack of voluntariness, lack of culpability (unconsciousness) or excuse. Automatism means that the defendant was not aware of his or her actions when making the particular movements that constituted the illegal act.

The criminal law of Canada is under the exclusive legislative jurisdiction of the Parliament of Canada. The power to enact criminal law is derived from section 91(27) of the Constitution Act, 1867. Most criminal laws have been codified in the Criminal Code, as well as the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, Youth Criminal Justice Act and several other peripheral statutes.

In criminal law and in the law of tort, recklessness may be defined as the state of mind where a person deliberately and unjustifiably pursues a course of action while consciously disregarding any risks flowing from such action. Recklessness is less culpable than malice, but is more blameworthy than carelessness.

In criminal law, intent is a subjective state of mind that must accompany the acts of certain crimes to constitute a violation. A more formal, generally synonymous legal term is scienter: intent or knowledge of wrongdoing.

In English criminal law, intention is one of the types of mens rea that, when accompanied by an actus reus, constitutes a crime.

The doctrine of common purpose, common design, joint enterprise, joint criminal enterprise or parasitic accessory liability is a common law legal doctrine that imputes criminal liability to the participants in a criminal enterprise for all reasonable results from that enterprise. The common purpose doctrine was established in English law, and later adopted in other common-law jurisdictions including Scotland, Ireland, Australia, Trinidad and Tobago, the Solomon Islands, Texas, the International Criminal Court, and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

Murder is an offence under the common law legal system of England and Wales. It is considered the most serious form of homicide, in which one person kills another with the intention to unlawfully cause either death or serious injury. The element of intentionality was originally termed malice aforethought, although it required neither malice nor premeditation. Baker, chapter 14 states that many killings done with a high degree of subjective recklessness were treated as murder from the 12th century right through until the 1974 decision in DPP v Hyam.

Duress in English law is a complete common law defence, operating in favour of those who commit crimes because they are forced or compelled to do so by the circumstances, or the threats of another. The doctrine arises not only in criminal law but also in civil law, where it is relevant to contract law and trusts law.

In the English law of homicide, manslaughter is a less serious offence than murder, the differential being between levels of fault based on the mens rea or by reason of a partial defence. In England and Wales, a common practice is to prefer a charge of murder, with the judge or defence able to introduce manslaughter as an option. The jury then decides whether the defendant is guilty or not guilty of either murder or manslaughter. On conviction for manslaughter, sentencing is at the judge's discretion, whereas a sentence of life imprisonment is mandatory on conviction for murder. Manslaughter may be either voluntary or involuntary, depending on whether the accused has the required mens rea for murder.

R v Bailey is a 1983 decision of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales considering criminal responsibility as to non-insane automatism. The broad questions addressed were whether a hampered state of mind, which the accused may have a legal and moral duty to lessen or avoid, gave him a legal excuse for his actions; and whether as to any incapacity there was strong countering evidence on the facts involved. The court ruled that the jury had been misdirected as to the effect of a defendant's mental state on his criminal liability. However, Bailey's defence had not been supported by sufficient evidence to support an acquittal and his appeal was dismissed.

English criminal law concerns offences, their prevention and the consequences, in England and Wales. Criminal conduct is considered to be a wrong against the whole of a community, rather than just the private individuals affected. The state, in addition to certain international organisations, has responsibility for crime prevention, for bringing the culprits to justice, and for dealing with convicted offenders. The police, the criminal courts and prisons are all publicly funded services, though the main focus of criminal law concerns the role of the courts, how they apply criminal statutes and common law, and why some forms of behaviour are considered criminal. The fundamentals of a crime are a guilty act and a guilty mental state. The traditional view is that moral culpability requires that a defendant should have recognised or intended that they were acting wrongly, although in modern regulation a large number of offences relating to road traffic, environmental damage, financial services and corporations, create strict liability that can be proven simply by the guilty act.

Fault, as a legal term, refers to legal blameworthiness and responsibility in each area of law. It refers to both the actus reus and the mental state of the defendant. The basic principle is that a defendant should be able to contemplate the harm that his actions may cause, and therefore should aim to avoid such actions. Different forms of liability employ different notions of fault, in some there is no need to prove fault, but the absence of it.

Burglary is a statutory offence in England and Wales.

In English criminal law, an inchoate offence is an offence relating to a criminal act which has not, or not yet, been committed. The main inchoate offences are attempting to commit; encouraging or assisting crime; and conspiring to commit. Attempts, governed by the Criminal Attempts Act 1981, are defined as situations where an individual who intends to commit an offence does an act which is "more than merely preparatory" in the offence's commission. Traditionally this definition has caused problems, with no firm rule on what constitutes a "more than merely preparatory" act, but broad judicial statements give some guidance. Incitement, on the other hand, is an offence under the common law, and covers situations where an individual encourages another person to engage in activities which will result in a criminal act taking place, and intends for this act to occur. As a criminal activity, incitement had a particularly broad remit, covering "a suggestion, proposal, request, exhortation, gesture, argument, persuasion, inducement, goading or the arousal of cupidity". Incitement was abolished by the Serious Crime Act 2007, but continues in other offences and as the basis of the new offence of "encouraging or assisting" the commission of a crime.

English law contains homicide offences – those acts involving the death of another person. For a crime to be considered homicide, it must take place after the victim's legally recognised birth, and before their legal death. There is also the usually uncontroversial requirement that the victim be under the "King's peace". The death must be causally linked to the actions of the defendant. Since the abolition of the year and a day rule, there is no maximum time period between any act being committed and the victim's death, so long as the former caused the latter.

R v Hibbert, [1995] 2 SCR 973, is a Supreme Court of Canada decision on aiding and abetting and the defence of duress in criminal law. The court held that duress is capable of negating the mens rea for some offences, but not for aiding the commission of an offence under s. 21(1)(b) of the Criminal Code. Nonetheless, duress can still function as an excuse-based defence.