Ragambald (died 786) was the Abbot of Farfa from 781 until his death. According to the abbey's twelfth-century historian Gregory of Catino, Ragambald was born in a city in Gaul (Gallia), that is, Francia, but he does not explicitly call him a Frank. [1] Succeeding Probatus, a local-born abbot, Ragambald was the first of a line of abbots from Francia, including Altpert (786–90) and Mauroald (790–802). [2] The significance of the Frankish presence at Farfa and of Ragambald's abbacy is summed up:

Gregory of Catino was a monk of the Abbey of Farfa and "one of the most accomplished monastic historians of his age." Gregory died shortly after 1130, possibly in 1133.

Gaul was a historical region of Western Europe during the Iron Age that was inhabited by Celtic tribes, encompassing present day France, Luxembourg, Belgium, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy, as well as the parts of the Netherlands and Germany on the west bank of the Rhine. It covered an area of 494,000 km2 (191,000 sq mi). According to the testimony of Julius Caesar, Gaul was divided into three parts: Gallia Celtica, Belgica, and Aquitania. Archaeologically, the Gauls were bearers of the La Tène culture, which extended across all of Gaul, as well as east to Raetia, Noricum, Pannonia, and southwestern Germania during the 5th to 1st centuries BC. During the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, Gaul fell under Roman rule: Gallia Cisalpina was conquered in 203 BC and Gallia Narbonensis in 123 BC. Gaul was invaded after 120 BC by the Cimbri and the Teutons, who were in turn defeated by the Romans by 103 BC. Julius Caesar finally subdued the remaining parts of Gaul in his campaigns of 58 to 51 BC.

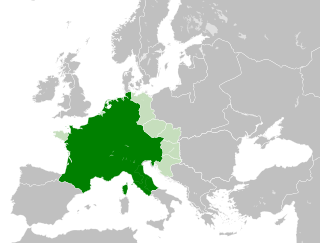

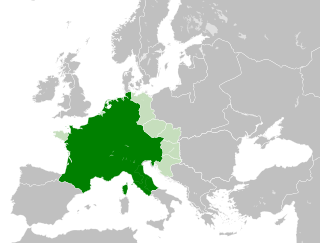

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks, or Frankish Empire was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. It is the predecessor of the modern states of France and Germany. After the Treaty of Verdun in 843, West Francia became the predecessor of France, and East Francia became that of Germany. Francia was among the last surviving Germanic kingdoms from the Migration Period era before its partition in 843.

. . . the ‘new’ abbeys of the time not only arose under Frankish influence but also infiltrated the religious life of Lombard Italy with ‘Frankish’ ideas and attitudes, providing a kind of ‘fifth column’ that prepared the way for Frankish military victory and a more ready acceptance of Frankish political domination. [3]

The Kingdom of the Lombards also known as the Lombard Kingdom; later the Kingdom of (all) Italy, was an early medieval state established by the Lombards, a Germanic people, on the Italian Peninsula in the latter part of the 6th century. The king was traditionally elected by the highest-ranking aristocrats, the dukes, as several attempts to establish a hereditary dynasty failed. The kingdom was subdivided into a varying number of duchies, ruled by semi-autonomous dukes, which were in turn subdivided into gastaldates at the municipal level. The capital of the kingdom and the center of its political life was Pavia in the modern northern Italian region of Lombardy.

A fifth column is any group of people who undermine a larger group from within, usually in favour of an enemy group or nation. The activities of a fifth column can be overt or clandestine. Forces gathered in secret can mobilize openly to assist an external attack. This term is also extended to organised actions by military personnel. Clandestine fifth column activities can involve acts of sabotage, disinformation, or espionage executed within defense lines by secret sympathizers with an external force.

Under Ragamblad the abbey's patronage may have declined as compared with that under his predecessor. He is recorded to have received a single grant from Duke Hildeprand of Spoleto during his tenure. This may have been related to Papal encroachments. By the reign of Pope Leo III, Farfa was losing land to the Papacy. [4]

Hildeprand was the Duke of Spoleto from 774 to 789.

Pope Leo III was Bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 26 December 795 to his death in 816. Protected by Charlemagne from his enemies in Rome, he subsequently strengthened Charlemagne's position by crowning him Holy Roman Emperor and "Augustus of the Romans".

Farfa Abbey is a territorial abbey in northern Lazio, central Italy. It is one of the most famous abbeys of Europe. It belongs to the Benedictine Order and is located about 60 km from Rome, in the commune of Fara Sabina, of which it is also a hamlet.

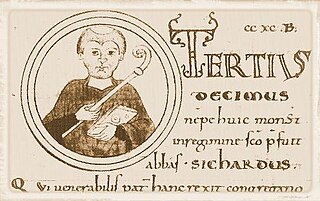

Sichard was a 9th century Italian Monk. He was the Abbot of Farfa from c.830 to 842. His abbacy corresponds with a drop in the number of property transactions involving Farfa, perhaps because "[its] wealth was by that time sufficient to cover major building at the abbey itself." Sichard added an oratory to the existing abbey.

Guicpert or Wigbert was the Abbot of Farfa for eleven months in 769–70 and probably also the Bishop of Rieti in 778. According to the twelfth-century chronicler of the abbey, Gregory of Catino, Wigbert was an Englishman and already a bishop when he convinced the dying Abbot Alan of Farfa to name him as his successor. From a twelfth-century perspective, Wigbert's accession was invalid because it was not in accordance with the Rule of Saint Benedict, although that rule was neither strictly nor uniformly enforced at Farfa in the eighth century. Nevertheless, the monks found Wigbert's rule a "tyranny" and sought the king, Desiderius, to remove him and confirm their freedom to elect a successor, which he did.

Wandelbert was the Abbot of Farfa sometime between 757 and 761, one of a series of abbots from Aquitaine. His abbacy coincided with a troubled period in the abbey's history and the stormy reign of Duke Gisulf of Spoleto, who seems to have brought some stability to the abbey by the time of his death.

Thomas of Maurienne was the first abbot of the Abbey of Farfa, which he founded between 680 and c.700. Although the sources of his life are much later, and he is surrounded by legends, his historicity is beyond doubt.

Anselm (Zelmo) was the Abbot of Farfa between 881 and 883, succeeding John I. His short abbacy is reasonably well-sourced compared to the string of five abbots following him, beginning with Teuto, who were extremely obscure figures even to Gregory of Catino, the abbey's historian of the eleventh century.

Vitalis was the "surrogate" Abbot of Farfa in 888, between the death of Spento and the election of the long-serving Peter. The history of the period in Farfa's history, besides the barest chronological outline, has been obscure since it was first written down, by Gregory of Catino in the late eleventh century.

Ingoald was the Abbot of Farfa from 815, succeeding Benedict. At the beginning of his abbacy he vigorously protested the policies of Pope Leo III (795–816), which had resulted in the abbey's loss of property. Ingoald complained about not only the—illegitimate, as he saw it—seizure of Farfa's lands, but also the application of dubious laws of Roman origin in a zone that followed Lombard law. While Ingoald also fostered close contacts with the Carolingian rulers of Francia and Lombardy, he resisted secular encroachments on the abbey's privileges as staunchly as he resisted papal ones. The rate of property transactions at Farfa seems to have peaked under Ingoald, but the surviving documentary evidence is far from complete.

Mauroald was a Frankish monk from Worms and the Abbot of Farfa from 790. Farfa, at less than a century old, was still interested in accruing territories through grants and donations in order to support its building projects and the expansion of its site.

Peter was the long-serving Abbot of Farfa from about 890 until his death. He replaced the interim abbot Vitalis. His abbacy marked the return of stability after a period which saw four abbots in the space of two years.

Benedict was the Abbot of Farfa, Italy from 802 until his death. He is the first abbot mentioned in the eleventh-century history of the abbey written by Gregory of Catino whose origins were not known.

Altpert was the Abbot of Farfa from the death of Ragambald in 786 until his own death a few years later. He was described by Gregory of Catino, writing some three centuries later, as having been born in Paris "of the Gauls" (Galliarum), presumably meaning that he was a Romance-speaking subject of the Carolingians. He increased the patronage of the abbey compared to his predecessor, but Farfa was still less successful in seeking out grants and donations than it had been under the local abbot Probatus. Altpert received a donation of lands at Rabenno from Duke Hildeprand of Spoleto, two other donations and one oblation.

Fulcoald was the fourth Abbot of Farfa from 740. In 739 King Liutprand granted Farfa the right of freedom in abbatial elections, but we do not know if Fulcoald was the product of such a free election or not. Like his predecessor, Lucerius, Fulcoald hailed from Aquitaine, then in southern Francia. "With his abbacy, the quantity of our [historical] evidence dramatically increases [and d]evelopments in secular politics can now be seen to impinge on Farfa's land acquisitions." Fulcoald's abbacy can therefore be defined in terms of three objectives that are apparent in the surviving sources: (a) to extend its landholdings and secure its rights to its properties, (b) to promote a strict and disciplined monastic observance, and (c) to "steer as untroubled a course as possible through the choppy waters of Italian politics".

Alan was an Aquitanian scholar, hermit and homilist who served as the sixth Abbot of Farfa in central Italy from 761. Before taking over at Farfa, Alan composed the Homiliarium Alani, "one of the most successful homiliaries of the late eighth and early ninth centuries", traces of which may be found in the liturgical formulae scattered throughout Farfa's eighth-century charters.

Perto was the Abbot of Farfa from 854/7 to 872. Between 857 and 859 he received a privilege from the Emperor Louis II confirming a cella called Santa Maria del Mignone. Since this is the first time Santa Maria is mentioned in Farfa's possession it may have been acquired around this time by Perto. Louis's diploma confirmed privileges granted Farfa by his father, Lothair I, in 840. The imperial diploma forbade any financial imposition on Farfa by any pope or secular ruler. This diploma may have been aimed at courting good relations with the pope or it may be associated with Louis's intervention in the Duchy of Spoleto in 860. In 864 Louis confirmed Farfa's possessions and, at the insistence of Bishop Peter of Spoleto, protector of the abbey since 840, made a donation to it in the region of Massa Torana.

John I was the Abbot of Farfa from 871/2. He made a few property acquisitions, but his abbacy comes at the start of an obscure period in Farfa's history. He received a confirmation from the Emperor Louis II of all of Farfa's lands on 27 May 872 and another from Charles the Bald in 875. Charles confirmed the abbey's freedom from taxation and secular jurisdiction and gave its abbots jurisdiction in suits involving subjects of the monastery's lands.

Hugh was the Abbot of Farfa from 998. He founded the abbatial school and wrote its history from the late ninth through the early eleventh century under the title Destructio monasterii Farfensis. A later student of his school, Gregory of Catino, wrote a fuller history of the monastery partly based on Hugh's earlier account.

Probatus was the Abbot of Farfa from 770 until 781, and the first abbot native to the Sabina. He steered the abbey through the fall of the Kingdom of the Lombards, trying to prevent the disastrous aggression of its last king, and kept it from falling under the jurisdiction of either the Papacy or the Papal States. With the benefit of his local connections he oversaw a great expansion of the abbey's properties through grants and purchases, and also rationalised its holdings to create a robust base for an early medieval monastic community.

The Libellus constructionis Farfensis, often referred to simply as the Constructio in context, is a written history of the Abbey of Farfa from its foundation by Thomas of Maurienne circa 700 until the death of Abbot Hilderic in 857. It is about the "construction" of a powerful abbey with vast landholdings. It was used as a source for two later histories, which are basically continuations: the Destructio monasterii Farfensis of Abbot Hugh and the Chronicon Farfense by Gregory of Catino.