Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at seventh in total abundance in the Milky Way and the Solar System. At standard temperature and pressure, two atoms of the element bond to form N2, a colourless and odourless diatomic gas. N2 forms about 78% of Earth's atmosphere, making it the most abundant chemical species in air. Because of the volatility of nitrogen compounds, nitrogen is relatively rare in the solid parts of the Earth.

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula NO−

3. Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are soluble in water. An example of an insoluble nitrate is bismuth oxynitrate.

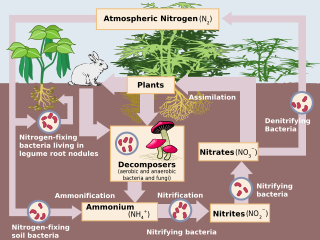

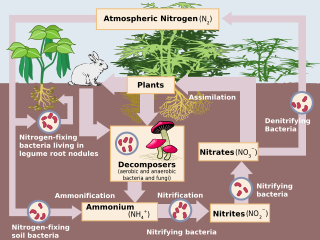

Nitrogen fixation is a chemical process by which molecular dinitrogen is converted into ammonia. It occurs both biologically and abiologically in chemical industries. Biological nitrogen fixation or diazotrophy is catalyzed by enzymes called nitrogenases. These enzyme complexes are encoded by the Nif genes and contain iron, often with a second metal.

A fertilizer or fertiliser is any material of natural or synthetic origin that is applied to soil or to plant tissues to supply plant nutrients. Fertilizers may be distinct from liming materials or other non-nutrient soil amendments. Many sources of fertilizer exist, both natural and industrially produced. For most modern agricultural practices, fertilization focuses on three main macro nutrients: nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) with occasional addition of supplements like rock flour for micronutrients. Farmers apply these fertilizers in a variety of ways: through dry or pelletized or liquid application processes, using large agricultural equipment, or hand-tool methods.

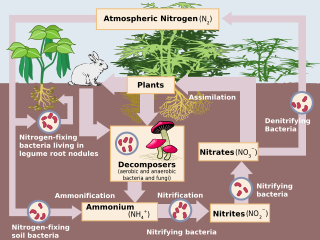

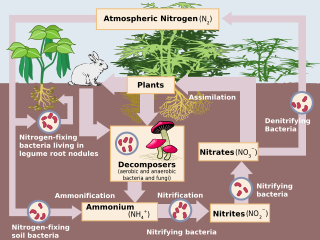

The nitrogen cycle is the biogeochemical cycle by which nitrogen is converted into multiple chemical forms as it circulates among atmospheric, terrestrial, and marine ecosystems. The conversion of nitrogen can be carried out through both biological and physical processes. Important processes in the nitrogen cycle include fixation, ammonification, nitrification, and denitrification. The majority of Earth's atmosphere (78%) is atmospheric nitrogen, making it the largest source of nitrogen. However, atmospheric nitrogen has limited availability for biological use, leading to a scarcity of usable nitrogen in many types of ecosystems.

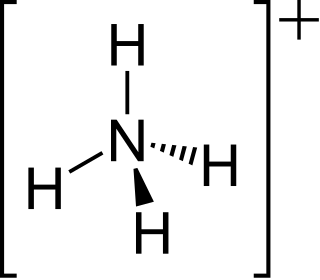

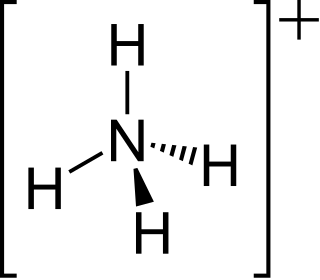

Ammonium is a modified form of ammonia that has an extra hydrogen atom. It is a positively charged (cationic) molecular ion with the chemical formula NH+4 or [NH4]+. It is formed by the addition of a proton to ammonia. Ammonium is also a general name for positively charged (protonated) substituted amines and quaternary ammonium cations, where one or more hydrogen atoms are replaced by organic or other groups. Not only is ammonium a source of nitrogen and a key metabolite for many living organisms, but it is an integral part of the global nitrogen cycle. As such, human impact in recent years could have an effect on the biological communities that depend on it.

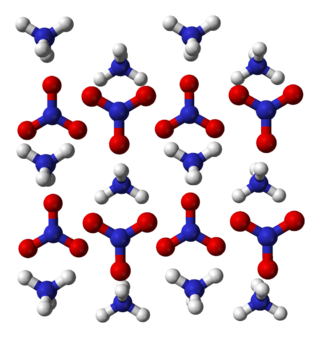

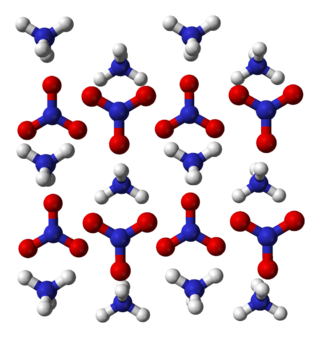

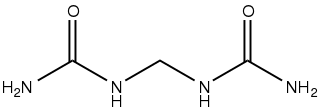

Ammonium nitrate is a chemical compound with the formula NH4NO3. It is a white crystalline salt consisting of ions of ammonium and nitrate. It is highly soluble in water and hygroscopic as a solid, although it does not form hydrates. It is predominantly used in agriculture as a high-nitrogen fertilizer.

Nitrification is the biological oxidation of ammonia to nitrate via the intermediary nitrite. Nitrification is an important step in the nitrogen cycle in soil. The process of complete nitrification may occur through separate organisms or entirely within one organism, as in comammox bacteria. The transformation of ammonia to nitrite is usually the rate limiting step of nitrification. Nitrification is an aerobic process performed by small groups of autotrophic bacteria and archaea.

Denitrification is a microbially facilitated process where nitrate (NO3−) is reduced and ultimately produces molecular nitrogen (N2) through a series of intermediate gaseous nitrogen oxide products. Facultative anaerobic bacteria perform denitrification as a type of respiration that reduces oxidized forms of nitrogen in response to the oxidation of an electron donor such as organic matter. The preferred nitrogen electron acceptors in order of most to least thermodynamically favorable include nitrate (NO3−), nitrite (NO2−), nitric oxide (NO), nitrous oxide (N2O) finally resulting in the production of dinitrogen (N2) completing the nitrogen cycle. Denitrifying microbes require a very low oxygen concentration of less than 10%, as well as organic C for energy. Since denitrification can remove NO3−, reducing its leaching to groundwater, it can be strategically used to treat sewage or animal residues of high nitrogen content. Denitrification can leak N2O, which is an ozone-depleting substance and a greenhouse gas that can have a considerable influence on global warming.

Nitrogen assimilation is the formation of organic nitrogen compounds like amino acids from inorganic nitrogen compounds present in the environment. Organisms like plants, fungi and certain bacteria that can fix nitrogen gas (N2) depend on the ability to assimilate nitrate or ammonia for their needs. Other organisms, like animals, depend entirely on organic nitrogen from their food.

Nitrosomonas is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria, belonging to the Betaproteobacteria. It is one of the five genera of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and, as an obligate chemolithoautotroph, uses ammonia as an energy source and carbon dioxide as a carbon source in the presence of oxygen. Nitrosomonas are important in the global biogeochemical nitrogen cycle, since they increase the bioavailability of nitrogen to plants and in the denitrification, which is important for the release of nitrous oxide, a powerful greenhouse gas. This microbe is photophobic, and usually generate a biofilm matrix, or form clumps with other microbes, to avoid light. Nitrosomonas can be divided into six lineages: the first one includes the species Nitrosomonas europea, Nitrosomonas eutropha, Nitrosomonas halophila, and Nitrosomonas mobilis. The second lineage presents the species Nitrosomonas communis, N. sp. I and N. sp. II. The third lineage includes only Nitrosomonas nitrosa. The fourth lineage includes the species Nitrosomonas ureae and Nitrosomonas oligotropha. The fifth and sixth lineages include the species Nitrosomonas marina, N. sp. III, Nitrosomonas estuarii, and Nitrosomonas cryotolerans.

In atmospheric chemistry, NOx is shorthand for nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide, the nitrogen oxides that are most relevant for air pollution. These gases contribute to the formation of smog and acid rain, as well as affecting tropospheric ozone.

Denitrifying bacteria are a diverse group of bacteria that encompass many different phyla. This group of bacteria, together with denitrifying fungi and archaea, is capable of performing denitrification as part of the nitrogen cycle. Denitrification is performed by a variety of denitrifying bacteria that are widely distributed in soils and sediments and that use oxidized nitrogen compounds such as nitrate and nitrite in the absence of oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor. They metabolize nitrogenous compounds using various enzymes, including nitrate reductase (NAR), nitrite reductase (NIR), nitric oxide reductase (NOR) and nitrous oxide reductase (NOS), turning nitrogen oxides back to nitrogen gas or nitrous oxide.

Ammonia production takes place worldwide, mostly in large-scale manufacturing plants that produce 183 million metric tonnes of ammonia (2021) annually. Leading producers are China (31.9%), Russia (8.7%), India (7.5%), and the United States (7.1%). 80% or more of ammonia is used as fertilizer. Ammonia is also used for the production of plastics, fibres, explosives, nitric acid, and intermediates for dyes and pharmaceuticals. The industry contributes 1% to 2% of global CO

2. Between 18–20 Mt of the gas is transported globally each year.

The chemical element nitrogen is one of the most abundant elements in the universe and can form many compounds. It can take several oxidation states; but the most common oxidation states are -3 and +3. Nitrogen can form nitride and nitrate ions. It also forms a part of nitric acid and nitrate salts. Nitrogen compounds also have an important role in organic chemistry, as nitrogen is part of proteins, amino acids and adenosine triphosphate.

Human impact on the nitrogen cycle is diverse. Agricultural and industrial nitrogen (N) inputs to the environment currently exceed inputs from natural N fixation. As a consequence of anthropogenic inputs, the global nitrogen cycle (Fig. 1) has been significantly altered over the past century. Global atmospheric nitrous oxide (N2O) mole fractions have increased from a pre-industrial value of ~270 nmol/mol to ~319 nmol/mol in 2005. Human activities account for over one-third of N2O emissions, most of which are due to the agricultural sector. This article is intended to give a brief review of the history of anthropogenic N inputs, and reported impacts of nitrogen inputs on selected terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.

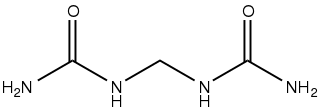

A controlled-release fertiliser (CRF) is a granulated fertiliser that releases nutrients gradually into the soil. Controlled-release fertilizer is also known as controlled-availability fertilizer, delayed-release fertilizer, metered-release fertilizer, or slow-acting fertilizer. Usually CRF refers to nitrogen-based fertilizers. Slow- and controlled-release involve only 0.15% of the fertilizer market (1995).

Nitrogen's effects on agriculture profoundly influence crop growth, soil fertility, and overall agricultural productivity, while also exerting significant impacts on the environment.

Dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA), also known as nitrate/nitrite ammonification, is the result of anaerobic respiration by chemoorganoheterotrophic microbes using nitrate (NO3−) as an electron acceptor for respiration. In anaerobic conditions microbes which undertake DNRA oxidise organic matter and use nitrate (rather than oxygen) as an electron acceptor, reducing it to nitrite, and then to ammonium (NO3− → NO2− → NH4+).

Nitroxylic acid or hydronitrous acid is an unstable reduced oxonitrogen acid. It has formula H4N2O4 containing nitrogen in the +2 oxidation state. The corresponding anion called nitroxylate is N

2O4−

4 or NO2−

2.