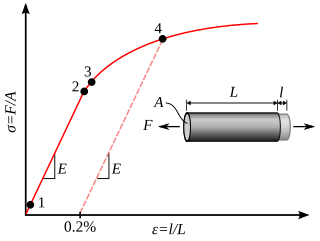

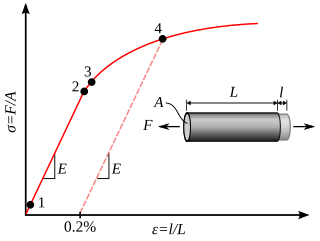

In physics and materials science, plasticity is the ability of a solid material to undergo permanent deformation, a non-reversible change of shape in response to applied forces. For example, a solid piece of metal being bent or pounded into a new shape displays plasticity as permanent changes occur within the material itself. In engineering, the transition from elastic behavior to plastic behavior is known as yielding.

In materials science, a dislocation or Taylor's dislocation is a linear crystallographic defect or irregularity within a crystal structure that contains an abrupt change in the arrangement of atoms. The movement of dislocations allow atoms to slide over each other at low stress levels and is known as glide or slip. The crystalline order is restored on either side of a glide dislocation but the atoms on one side have moved by one position. The crystalline order is not fully restored with a partial dislocation. A dislocation defines the boundary between slipped and unslipped regions of material and as a result, must either form a complete loop, intersect other dislocations or defects, or extend to the edges of the crystal. A dislocation can be characterised by the distance and direction of movement it causes to atoms which is defined by the Burgers vector. Plastic deformation of a material occurs by the creation and movement of many dislocations. The number and arrangement of dislocations influences many of the properties of materials.

In materials science, work hardening, also known as strain hardening, is the strengthening of a metal or polymer by plastic deformation. Work hardening may be desirable, undesirable, or inconsequential, depending on the context.

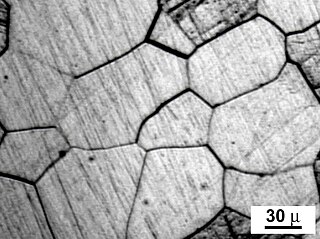

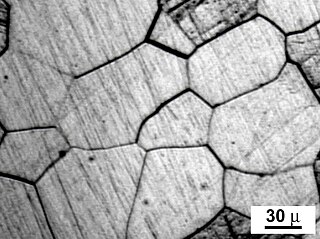

In materials science, a grain boundary is the interface between two grains, or crystallites, in a polycrystalline material. Grain boundaries are two-dimensional defects in the crystal structure, and tend to decrease the electrical and thermal conductivity of the material. Most grain boundaries are preferred sites for the onset of corrosion and for the precipitation of new phases from the solid. They are also important to many of the mechanisms of creep. On the other hand, grain boundaries disrupt the motion of dislocations through a material, so reducing crystallite size is a common way to improve mechanical strength, as described by the Hall–Petch relationship.

Crystal twinning occurs when two or more adjacent crystals of the same mineral are oriented so that they share some of the same crystal lattice points in a symmetrical manner. The result is an intergrowth of two separate crystals that are tightly bonded to each other. The surface along which the lattice points are shared in twinned crystals is called a composition surface or twin plane.

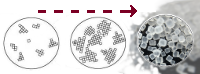

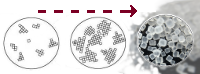

Dynamic recrystallization (DRX) is a type of recrystallization process, found within the fields of metallurgy and geology. In dynamic recrystallization, as opposed to static recrystallization, the nucleation and growth of new grains occurs during deformation rather than afterwards as part of a separate heat treatment. The reduction of grain size increases the risk of grain boundary sliding at elevated temperatures, while also decreasing dislocation mobility within the material. The new grains are less strained, causing a decrease in the hardening of a material. Dynamic recrystallization allows for new grain sizes and orientation, which can prevent crack propagation. Rather than strain causing the material to fracture, strain can initiate the growth of a new grain, consuming atoms from neighboring pre-existing grains. After dynamic recrystallization, the ductility of the material increases.

Mylonite is a fine-grained, compact metamorphic rock produced by dynamic recrystallization of the constituent minerals resulting in a reduction of the grain size of the rock. Mylonites can have many different mineralogical compositions; it is a classification based on the textural appearance of the rock.

In metallurgy and materials science, annealing is a heat treatment that alters the physical and sometimes chemical properties of a material to increase its ductility and reduce its hardness, making it more workable. It involves heating a material above its recrystallization temperature, maintaining a suitable temperature for an appropriate amount of time and then cooling.

In materials science, recrystallization is a process by which deformed grains are replaced by a new set of defect-free grains that nucleate and grow until the original grains have been entirely consumed. Recrystallization is usually accompanied by a reduction in the strength and hardness of a material and a simultaneous increase in the ductility. Thus, the process may be introduced as a deliberate step in metals processing or may be an undesirable byproduct of another processing step. The most important industrial uses are softening of metals previously hardened or rendered brittle by cold work, and control of the grain structure in the final product. Recrystallization temperature is typically 0.3–0.4 times the melting point for pure metals and 0.5 times for alloys.

The stacking-fault energy (SFE) is a materials property on a very small scale. It is noted as γSFE in units of energy per area.

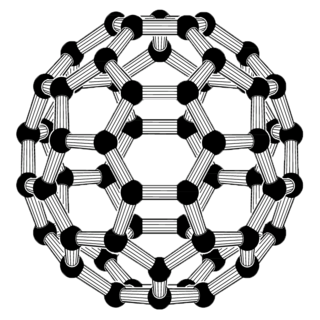

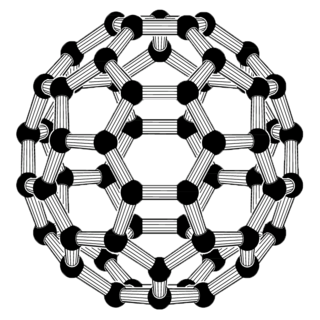

A nanocrystalline (NC) material is a polycrystalline material with a crystallite size of only a few nanometers. These materials fill the gap between amorphous materials without any long range order and conventional coarse-grained materials. Definitions vary, but nanocrystalline material is commonly defined as a crystallite (grain) size below 100 nm. Grain sizes from 100–500 nm are typically considered "ultrafine" grains.

In metallurgy, materials science and structural geology, subgrain rotation recrystallization is recognized as an important mechanism for dynamic recrystallisation. It involves the rotation of initially low-angle sub-grain boundaries until the mismatch between the crystal lattices across the boundary is sufficient for them to be regarded as grain boundaries. This mechanism has been recognized in many minerals and in metals.

A deformation mechanism, in geology, is a process occurring at a microscopic scale that is responsible for changes in a material's internal structure, shape and volume. The process involves planar discontinuity and/or displacement of atoms from their original position within a crystal lattice structure. These small changes are preserved in various microstructures of materials such as rocks, metals and plastics, and can be studied in depth using optical or digital microscopy.

Methods have been devised to modify the yield strength, ductility, and toughness of both crystalline and amorphous materials. These strengthening mechanisms give engineers the ability to tailor the mechanical properties of materials to suit a variety of different applications. For example, the favorable properties of steel result from interstitial incorporation of carbon into the iron lattice. Brass, a binary alloy of copper and zinc, has superior mechanical properties compared to its constituent metals due to solution strengthening. Work hardening has also been used for centuries by blacksmiths to introduce dislocations into materials, increasing their yield strengths.

In materials science, grain-boundary strengthening is a method of strengthening materials by changing their average crystallite (grain) size. It is based on the observation that grain boundaries are insurmountable borders for dislocations and that the number of dislocations within a grain has an effect on how stress builds up in the adjacent grain, which will eventually activate dislocation sources and thus enabling deformation in the neighbouring grain as well. By changing grain size, one can influence the number of dislocations piled up at the grain boundary and yield strength. For example, heat treatment after plastic deformation and changing the rate of solidification are ways to alter grain size.

Severe plastic deformation (SPD) is a generic term describing a group of metalworking techniques involving very large strains typically involving a complex stress state or high shear, resulting in a high defect density and equiaxed "ultrafine" grain (UFG) size or nanocrystalline (NC) structure.

Quartz is the most abundant single mineral in the earth's crust, and as such is present in a very large proportion of rocks both as primary crystals and as detrital grains in sedimentary and metamorphic rocks. Dynamic recrystallization is a process of crystal regrowth under conditions of stress and elevated temperature, commonly applied in the fields of metallurgy and materials science. Dynamic quartz recrystallization happens in a relatively predictable way with relation to temperature, and given its abundance quartz recrystallization can be used to easily determine relative temperature profiles, for example in orogenic belts or near intrusions.

Grain boundary sliding (GBS) is a material deformation mechanism where grains slide against each other. This occurs in polycrystalline material under external stress at high homologous temperature and low strain rate and is intertwined with creep. Homologous temperature describes the operating temperature relative to the melting temperature of the material. There are mainly two types of grain boundary sliding: Rachinger sliding, and Lifshitz sliding. Grain boundary sliding usually occurs as a combination of both types of sliding. Boundary shape often determines the rate and extent of grain boundary sliding.

Paleostress inversion refers to the determination of paleostress history from evidence found in rocks, based on the principle that past tectonic stress should have left traces in the rocks. Such relationships have been discovered from field studies for years: qualitative and quantitative analyses of deformation structures are useful for understanding the distribution and transformation of paleostress fields controlled by sequential tectonic events. Deformation ranges from microscopic to regional scale, and from brittle to ductile behaviour, depending on the rheology of the rock, orientation and magnitude of the stress etc. Therefore, detailed observations in outcrops, as well as in thin sections, are important in reconstructing the paleostress trajectories.

Microstructurally stable nanocrystalline alloys are alloys that are designed to resist microstructural coarsening under various thermo-mechanical loading conditions.