Exile or banishment, is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons and peoples suffer exile, but sometimes social entities like institutions are forced from their homeland.

Gaius Musonius Rufus was a Roman Stoic philosopher of the 1st century AD. He taught philosophy in Rome during the reign of Nero and so was sent into exile in 65 AD, returning to Rome only under Galba. He was allowed to stay in Rome when Vespasian banished all other philosophers from the city in 71 AD although he was eventually banished anyway, returning only after Vespasian's death. A collection of extracts from his lectures still survives. He is also remembered for being the teacher of Epictetus and Dio Chrysostom.

Delator is Latin for a denouncer, one who indicates to a court another as having committed a punishable deed.

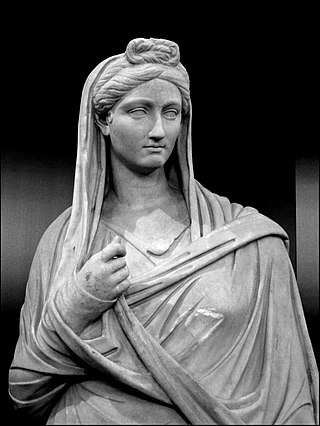

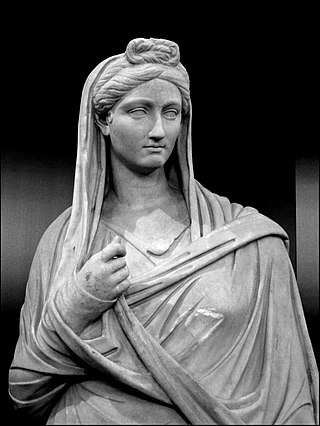

Freeborn women in ancient Rome were citizens (cives), but could not vote or hold political office. Because of their limited public role, women are named less frequently than men by Roman historians. But while Roman women held no direct political power, those from wealthy or powerful families could and did exert influence through private negotiations. Exceptional women who left an undeniable mark on history include Lucretia and Claudia Quinta, whose stories took on mythic significance; fierce Republican-era women such as Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi, and Fulvia, who commanded an army and issued coins bearing her image; women of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, most prominently Livia and Agrippina the Younger, who contributed to the formation of Imperial mores; and the empress Helena, a driving force in promoting Christianity.

Helvidius Priscus, Stoic philosopher and statesman, lived during the reigns of Nero, Galba, Otho, Vitellius and Vespasian.

When Vespasian sent for Helvidius Priscus and commanded him not to go into the senate, he replied, "It is in your power not to allow me to be a member of the senate, but so long as I am, I must go in." "Well, go in then," says the emperor, "but say nothing." "Do not ask my opinion, and I will be silent." "But I must ask your opinion." "And I must say what I think right." "But if you do, I shall put you to death." "When then did I tell you that I am immortal? You will do your part, and I will do mine: it is your part to kill; it is mine to die, but not in fear: yours to banish me; mine to depart without sorrow." Epictetus, Discourses, 1.2.19–21

Pity is a sympathetic sorrow evoked by the suffering of others. The word is comparable to compassion, condolence, or empathy. It derives from the Latin pietas. Self-pity is pity directed towards oneself.

Gyaros, also locally known as Gioura, is an arid, unpopulated, and uninhabited Greek island in the northern Cyclades near the islands of Andros and Tinos, with an area of 23 square kilometres (9 sq mi). It is a part of the municipality of Ano Syros, which lies primarily on the island of Syros. This and other small islands of the Aegean Sea served as places of exile for important persons in the early Roman empire. The extremity of its desolation was proverbial among Roman authors, such as Tacitus and Juvenal. It was a place of exile for left-wing political dissidents in Greece from 1948 until 1974. During that time, at least 22,000 people were exiled or imprisoned on the island. It is an island of great ecological importance as it hosts the largest population of monk seals in the Mediterranean.

Demaratus, frequently called Demaratus of Corinth, was the father of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, the fifth King of Rome, the grandfather or great-grandfather of Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the seventh and last Roman king, and an ancestor of Lucius Junius Brutus and Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, the first consuls of the Roman Republic.

The naval Battle of Giglio or Montecristo was a military clash between a fleet of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II and a fleet of the Republic of Genoa in the Tyrrhenian Sea. It took place on Friday, May 3, 1241 between the islands of Montecristo and Giglio in the Tuscan Archipelago and ended with the victory of the Imperial fleet.

Decimus Junius Juvenalis, known in English as Juvenal, was a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century AD. He is the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the Satires. The details of Juvenal's life are unclear, although references within his text to known persons of the late first and early second centuries AD fix his earliest date of composition. One recent scholar argues that his first book was published in 100 or 101. A reference to a political figure dates his fifth and final surviving book to sometime after 127.

Marcus Aurelius Cotta Maximus Messalinus was a Roman Senator who was a friend of the first two Roman emperors Augustus and Tiberius.

Paullus Fabius Maximus was a Roman senator, active toward the end of the first century BC. He was consul in 11 BC as the colleague of Quintus Aelius Tubero, and a confidant of emperor Augustus.

Ovid, the Latin poet of the Roman Empire, was banished in 8 AD from Rome to Tomis by decree of the emperor Augustus. The reasons for his banishment are uncertain. Ovid's exile is related by the poet himself, and also in brief references to the event by Pliny the Elder and Statius. At the time, Tomis was a remote town on the edge of the civilized world; it was loosely under the authority of the Kingdom of Thrace, and was superficially Hellenized. According to Ovid, none of its citizens spoke Latin, which as an educated Roman, he found trying. Ovid wrote that the cause of his exile was carmen et error, probably the Ars Amatoria and a personal indiscretion or mistake. The council of the city of Rome revoked his exile in December 2017, 2,009 years after his banishment.

Gaius Junius Silanus was a Roman Senator active during the reigns of Augustus and Tiberius. He acceded to the rank of Roman consul in 10 AD as the colleague of Publius Cornelius Dolabella. For the term 20/21 the sortition selected him to be proconsul of Asia. However, upon his return to Rome in 22 he was accused of malversation (misconduct). To this alleged crime his accusers in the senate added the charges of treason (majestas) and sacrilege to the divinity of Augustus.

Publius Suillius Rufus was a Roman senator who was active during the Principate. He was notorious for his prosecutions during the reign of Claudius; and he was the husband of the step-daughter of Ovid. Rufus was suffect consul in the nundinium of November-December 41 as the colleague of Quintus Ostorius Scapula.

The gens Helvidia was a plebeian family at Rome. Members of this gens are first mentioned in the final decades of the Republic. A century later, the Helvidii distinguished themselves by what has been called their "earnest, but fruitless, patriotism."

The gens Paconia was a minor plebeian family at ancient Rome. No members of this gens obtained any of the higher offices of the Roman state in the time of the Republic, but Aulus Paconius Sabinus held the consulship in AD 58, during the reign of Nero.

The Stoic Opposition is the name given to a group of Stoic philosophers who actively opposed the autocratic rule of certain emperors in the 1st-century, particularly Nero and Domitian. Most prominent among them was Thrasea Paetus, an influential Roman senator executed by Nero. They were held in high regard by the later Stoics Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius. Thrasea, Rubellius Plautus and Barea Soranus were reputedly students of the famous Stoic teacher Musonius Rufus and as all three were executed by Nero they became known collectively as the Stoic martyrs.

Baebius Massa, was a governor of Hispania Baetica in 92. He was an equestrian procurator of Africa in 70 and was promoted to the Senate by Vespasian as a reward for his part in the suppression of a revolt.

Pay in the Roman army was defined by the annual stipendium received by a Roman soldier, of whatever rank he was, from the Republican era until the Later Roman Empire. It constituted the main part of the Roman soldier's income, who from the end of the Republic began to receive, in addition to the spoils of war, prize money called donativa. The latter grew to such an extent in the following centuries that by the 4th century, the ancient stipendium constituted only 10–15% of the Roman legionary's entire income.