Hydropower, also known as water power, is the use of falling or fast-running water to produce electricity or to power machines. This is achieved by converting the gravitational potential or kinetic energy of a water source to produce power. Hydropower is a method of sustainable energy production.

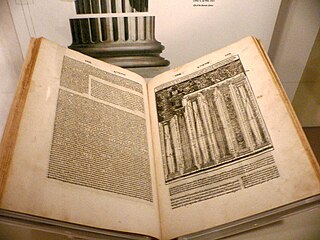

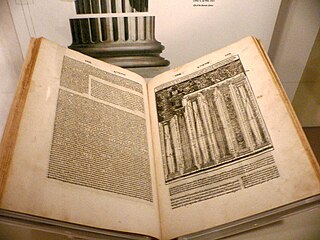

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, commonly known as Vitruvius, was a Roman author, architect, and civil and military engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work entitled De architectura. He originated the idea that all buildings should have three attributes: firmitas, utilitas, and venustas. These principles were later widely adopted in Roman architecture. His discussion of perfect proportion in architecture and the human body led to the famous Renaissance drawing of the Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci.

A watermill or water mill is a mill that uses hydropower. It is a structure that uses a water wheel or water turbine to drive a mechanical process such as milling (grinding), rolling, or hammering. Such processes are needed in the production of many material goods, including flour, lumber, paper, textiles, and many metal products. These watermills may comprise gristmills, sawmills, paper mills, textile mills, hammermills, trip hammering mills, rolling mills, wire drawing mills.

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel, with a number of blades or buckets arranged on the outside rim forming the driving car.

A noria is a hydropowered machine used to lift water into a small aqueduct, either for the purpose of irrigation or to supply water to cities and villages.

A crank is an arm attached at a right angle to a rotating shaft by which circular motion is imparted to or received from the shaft. When combined with a connecting rod, it can be used to convert circular motion into reciprocating motion, or vice versa. The arm may be a bent portion of the shaft, or a separate arm or disk attached to it. Attached to the end of the crank by a pivot is a rod, usually called a connecting rod (conrod).

The chain pump is type of a water pump in which several circular discs are positioned on an endless chain. One part of the chain dips into the water, and the chain runs through a tube, slightly bigger than the diameter of the discs. As the chain is drawn up the tube, water becomes trapped between the discs and is lifted to and discharged at the top. Chain pumps were used for centuries in the ancient Middle East, Europe, and China.

An aeolipile, aeolipyle, or eolipile, also known as a Hero's engine, is a simple, bladeless radial steam turbine which spins when the central water container is heated. Torque is produced by steam jets exiting the turbine. The Greek-Egyptian mathematician and engineer Hero of Alexandria described the device in the 1st century AD, and many sources give him the credit for its invention. However, Vitruvius was the first to describe this appliance in his De architectura.

A trip hammer, also known as a tilt hammer or helve hammer, is a massive powered hammer. Traditional uses of trip hammers include pounding, decorticating and polishing of grain in agriculture. In mining, trip hammers were used for crushing metal ores into small pieces, although a stamp mill was more usual for this. In finery forges they were used for drawing out blooms made from wrought iron into more workable bar iron. They were also used for fabricating various articles of wrought iron, latten, steel and other metals.

The Dolaucothi Gold Mines, also known as the Ogofau Gold Mine, are ancient Roman surface and underground mines located in the valley of the River Cothi, near Pumsaint, Carmarthenshire, Wales. The gold mines are located within the Dolaucothi Estate which is now owned by the National Trust.

De architectura is a treatise on architecture written by the Roman architect and military engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio and dedicated to his patron, the emperor Caesar Augustus, as a guide for building projects. As the only treatise on architecture to survive from antiquity, it has been regarded since the Renaissance as the first book on architectural theory, as well as a major source on the canon of classical architecture. It contains a variety of information on Greek and Roman buildings, as well as prescriptions for the planning and design of military camps, cities, and structures both large and small. Since Vitruvius published before the development of cross vaulting, domes, concrete, and other innovations associated with Imperial Roman architecture, his ten books give no information on these hallmarks of Roman building design and technology.

The ancient Romans were famous for their advanced engineering accomplishments. Technology for bringing running water into cities was developed in the east, but transformed by the Romans into a technology inconceivable in Greece. The architecture used in Rome was strongly influenced by Greek and Etruscan sources.

A stamp mill is a type of mill machine that crushes material by pounding rather than grinding, either for further processing or for extraction of metallic ores. Breaking material down is a type of unit operation.

The technology history of the Roman military covers the development of and application of technologies for use in the armies and navies of Rome from the Roman Republic to the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The rise of Hellenism and the Roman Republic are generally seen as signalling the end of the Iron Age in the Mediterranean. Roman iron-working was enhanced by a process known as carburization. The Romans used the better properties in their armaments, and the 1,300 years of Roman military technology saw radical changes. The Roman armies of the early empire were much better equipped than early republican armies. Metals used for arms and armor primarily included iron, bronze, and brass. For construction, the army used wood, earth, and stone. The later use of concrete in architecture was widely mirrored in Roman military technology, especially in the application of a military workforce to civilian construction projects.

The Barbegal aqueduct and mills is a Roman watermill complex located on the territory of the commune of Fontvieille, near the town of Arles, in southern France. The complex has been referred to as "the greatest known concentration of mechanical power in the ancient world" and the sixteen overshot wheels are considered the biggest ancient mill complex.

Mining was one of the most prosperous activities in Roman Britain. Britain was rich in resources such as copper, gold, iron, lead, salt, silver, and tin, materials in high demand in the Roman Empire. Sufficient supply of metals was needed to fulfill the demand for coinage and luxury artefacts by the elite.The Romans started panning and puddling for gold. The abundance of mineral resources in the British Isles was probably one of the reasons for the Roman conquest of Britain. They were able to use advanced technology to find, develop and extract valuable minerals on a scale unequaled until the Middle ages.

Roman technology is the collection of antiques, skills, methods, processes, and engineering practices which supported Roman civilization and made possible the expansion of the economy and military of ancient Rome.

A sāqiyah or saqiya, also spelled sakia or saqia) is a mechanical water lifting device. It is also called a Persian wheel, tablia, rehat, and in Latin tympanum. It is similar in function to a scoop wheel, which uses buckets, jars, or scoops fastened either directly to a vertical wheel, or to an endless belt activated by such a wheel. The vertical wheel is itself attached by a drive shaft to a horizontal wheel, which is traditionally set in motion by animal power Because it is not using the power of flowing water, the sāqiyah is different from a noria and any other type of water wheel.

Metals and metal working had been known to the people of modern Italy since the Bronze Age. By 53 BC, Rome had expanded to control an immense expanse of the Mediterranean. This included Italy and its islands, Spain, Macedonia, Africa, Asia Minor, Syria and Greece; by the end of the Emperor Trajan's reign, the Roman Empire had grown further to encompass parts of Britain, Egypt, all of modern Germany west of the Rhine, Dacia, Noricum, Judea, Armenia, Illyria, and Thrace. As the empire grew, so did its need for metals.

De Skarrenmolen is a smock mill in Scharsterbrug, Friesland, Netherlands which was built in 1888. The mill has been restored to working order. It is listed as a Rijksmonument.