The French Revolution was a period of political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789, and ended with the coup of 18 Brumaire in November 1799 and the formation of the French Consulate. Many of its ideas are considered fundamental principles of liberal democracy, while its values and institutions remain central to modern French political discourse.

In the history of France, the First Republic, sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic, was founded on 21 September 1792 during the French Revolution. The First Republic lasted until the declaration of the First Empire on 18 May 1804 under Napoléon Bonaparte, although the form of government changed several times.

The Society of the Friends of the Constitution, renamed the Society of the Jacobins, Friends of Freedom and Equality after 1792 and commonly known as the Jacobin Club or simply the Jacobins, was the most influential political club during the French Revolution of 1789. The period of its political ascendancy includes the Reign of Terror, during which well over 10,000 people were put on trial and executed in France, many for political crimes.

Claude Antoine, comte Prieur-Duvernois (1763–1832), commonly known as Prieur de la Côte-d'Or after his native département, was a French engineer and a politician during and after the French Revolution.

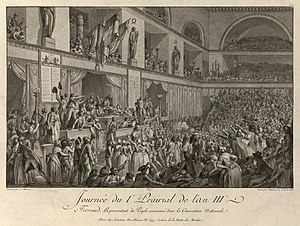

The National Convention was the constituent assembly of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for its first three years during the French Revolution, following the two-year National Constituent Assembly and the one-year Legislative Assembly. Created after the great insurrection of 10 August 1792, it was the first French government organized as a republic, abandoning the monarchy altogether. The Convention sat as a single-chamber assembly from 20 September 1792 to 26 October 1795.

In the historiography of the French Revolution, the Thermidorian Reaction is the common term for the period between the ousting of Maximilien Robespierre on 9 Thermidor II, or 27 July 1794, and the inauguration of the French Directory on 2 November 1795.

Jean-Lambert Tallien was a French politician of the revolutionary period. Though initially an active agent of the Reign of Terror, he eventually clashed with its leader, Maximilien Robespierre, and is best known as one of the key figures of the Thermidorian Reaction that led to the fall of Robespierre and the end of the Terror.

The historiography of the French Revolution stretches back over two hundred years.

The Coup of 18 Brumaire brought Napoleon Bonaparte to power as First Consul of the French First Republic. In the view of most historians, it ended the French Revolution and would soon lead to the coronation of Napoleon as Emperor of the French. This bloodless coup d'état overthrew the Directory, replacing it with the French Consulate. This occurred on 9 November 1799, which was 18 Brumaire, Year VIII, under the short-lived French Republican calendar system.

The War of the Second Coalition was the second war targeting revolutionary France by many European monarchies, led by Britain, Austria, and Russia and including the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, Naples and various German monarchies. Prussia did not join the coalition, while Spain supported France.

The Great Fear was a general panic that took place between 22 July to 6 August 1789, at the start of the French Revolution. Rural unrest had been present in France since the worsening grain shortage of the spring. Fuelled by rumours of an aristocrats' "famine plot" to starve or burn out the population, both peasants and townspeople mobilised in many regions.

Georges Lefebvre was a French historian, best known for his work on the French Revolution and peasant life. He is considered one of the pioneers of "history from below". He coined the phrase the "death certificate of the old order" to describe the Great Fear of 1789. Among his most significant works was the 1924 book Les Paysans du Nord pendant la Révolution française, which was the result of 20 years of research into the role of the peasantry during the revolutionary period.

The Revolutionary Tribunal was a court instituted by the National Convention during the French Revolution for the trial of political offenders. In October 1793, it became one of the most powerful engines of the period often called the Reign of Terror.

George Frederick Elliot Rudé was a British Marxist historian, specializing in the French Revolution and "history from below", especially the importance of crowds in history.

Alfred Bert Carter Cobban was an English historian and Professor of French History at University College, London, who along with prominent French historian François Furet advocated a classical liberal view of the French Revolution.

Legislative elections were held in France between 9 and 18 April 1798 to elect one-third of the members of the Council of Five Hundred and the Council of Ancients, the lower and upper houses of the legislature, as well as 201 vacant seats. They marked the beginning of the end of the French far-left and rise of the anti-Montagnard and anti-Jacobin groupings. The 1798 elections were partially invalidated by the passage of the Law of 22 Floréal Year VI which saw 106 Montagnards lose their seats by decree of the Council of Five Hundred.

Legislative elections were held in France between 12 and 21 October 1795 to elect one-third of the members of the Council of Five Hundred and the Council of Ancients, the lower and upper houses of the legislature. The elections were held in accordance with the Constitution of the Year III and the first under the French Directory.

The White Terror was a period during the French Revolution in 1795 when a wave of violent attacks swept across much of France. The victims of this violence were people identified as being associated with the Reign of Terror – followers of Robespierre and Marat, and members of local Jacobin clubs. The violence was perpetrated primarily by those whose relatives or associates had been victims of the Great Terror, or whose lives and livelihoods had been threatened by the government and its supporters before the Thermidorean Reaction. Principally, these were, in Paris, the Muscadins, and in the countryside, monarchists, supporters of the Girondins, those who opposed the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and those otherwise hostile to the Jacobin political agenda.

The insurrection of 12 Germinal Year III was a popular revolt in Paris on 1 April 1795 against the policies of the Thermidorian Convention. It was provoked by poverty and hunger resulting from the abandonment of the controlled economy after the dismantling of the Revolutionary Government during Thermidorian Reaction.