Related Research Articles

William Stukeley was an English antiquarian, physician and Anglican clergyman. A significant influence on the later development of archaeology, he pioneered the scholarly investigation of the prehistoric monuments of Stonehenge and Avebury in Wiltshire. He published over twenty books on archaeology and other subjects during his lifetime. Born in Holbeach, Lincolnshire, as the son of a lawyer, Stukeley worked in his father's law business before attending Saint Benet's College, Cambridge. In 1709, he began studying medicine at St Thomas' Hospital, Southwark, before working as a general practitioner in Boston, Lincolnshire.

George Vertue was an English engraver and antiquary, whose notebooks on British art of the first half of the 18th century are a valuable source for the period.

Charles Francis Christopher Hawkes, FBA, FSA was an English archaeologist specialising in European prehistory. He was Professor of European Archaeology at the University of Oxford from 1946 to 1972.

St Pancras Old Church is a Church of England parish church on Pancras Road, Somers Town, in the London Borough of Camden. Somers Town is an area of the ancient parish and later Metropolitan Borough of St Pancras.

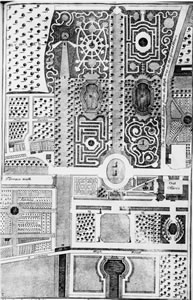

Batty Langley was an English garden designer, and prolific writer who produced a number of engraved designs for "Gothick" structures, summerhouses and garden seats in the years before the mid-18th century.

Sir Charles Leonard Woolley was a British archaeologist best known for his excavations at Ur in Mesopotamia. He is recognized as one of the first "modern" archaeologists who excavated in a methodical way, keeping careful records, and using them to reconstruct ancient life and history. Woolley was knighted in 1935 for his contributions to the discipline of archaeology. He was married to the British archaeologist Katharine Woolley.

Risley Hall is a country house used as a hotel set in 17 acres (69,000 m2) of private landscaped grounds in the Derbyshire countryside, near the village of Risley, England. It has 35 bedrooms, function rooms and caters for weddings, which take place in the 16th-century Great Hall. A Spa closed down in 2016 as is yet to be reopened.

Samuel Pegge "the Elder" was an English antiquary and clergyman.

Shaun Greenhalgh is a British artist and former art forger. Over a seventeen-year period, between 1989 and 2006, he produced a large number of forgeries. With the assistance of his brother and elderly parents, who fronted the sales side of the operation, he successfully sold his fakes internationally to museums, auction houses, and private buyers, accruing nearly £1 million.

The Amarna Princess, sometimes referred to as the "Bolton Amarna Princess," is a statue forged by British art forger Shaun Greenhalgh and sold by his father George Sr. to Bolton Museum for £440,000 in 2003. Based on the Amarna art-style of ancient Egypt, the purchase of the Amarna Princess was feted as a "coup" by the museum and it remained on display for three years. However, in November 2005, Greenhalgh was brought under suspicion by Scotland Yard's Arts and Antiquities Unit, and the statue was impounded for further examination in March 2006. It is now displayed as a part of an exhibition of fakes and forgeries.

Bolton Art Gallery, Library & Museum is a public museum, art gallery, library and aquarium in the town of Bolton, England, owned by Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council. The museum, Bolton Museum, is housed within the grade II listed Le Mans Crescent near Bolton Town Hall and shares its main entrance with the library, Bolton Central Library, in a purpose-built civic centre.

A lanx was a large ancient Roman serving platter. Particularly ornamented ones were used to make offerings or sacrifices. Indeed, the silver Corbridge Lanx, the second discovered in Britain, has depicted on it a lanx itself, set beside various gods and goddesses: Minerva, Diana, Juno, Vesta and Apollo.

The Faun is a sculpture by British forger Shaun Greenhalgh. He successfully passed it off as a work by Paul Gauguin, selling it at Sotheby's for £20,700 in 1994. Three years later, in 1997, it was bought by the Art Institute of Chicago for an undisclosed sum, thought to be about $125,000. It was hailed by them as "one of its most important acquisitions in the last twenty years."

The Description of Britain, also known by its Latin name De Situ Britanniae, was a literary forgery perpetrated by Charles Bertram on the historians of England. It purported to be a 15th-century manuscript by the English monk Richard of Westminster, including information from a lost contemporary account of Britain by a Roman general, new details of the Roman roads in Britain in the style of the Antonine Itinerary, and "an antient map" as detailed as the works of Ptolemy. Bertram disclosed the existence of the work through his correspondence with the antiquarian William Stukeley by 1748, provided him "a copy" which was made available in London by 1749, and published it in Latin in 1757. By this point, his Richard had become conflated with the historical Richard of Cirencester. The text was treated as a legitimate and major source of information on Roman Britain from the 1750s through the 19th century, when it was progressively debunked by John Hodgson, Karl Wex, B. B. Woodward, and John E. B. Mayor. Effects from the forgery can still be found in works on British history and it is generally credited with having named the Pennine Mountains.

Alexander Gordon was a Scottish antiquary and singer. His survey of Roman sites, the Itinerarium Septentrionale, was considered an essential reference by all Roman antiquaries of his time.

The Eadred Reliquary was one of the wide-ranging art forgeries produced by Shaun Greenhalgh and his family, of Bolton, Greater Manchester.

Sir Charles James Jackson was a British businessman, collector, barrister, newspaper executive, politician, and writer, who was an authority on antique gold and silver plate.

The following outline is provided as an overview and topical guide to forgery:

The Esquiline Treasure is an ancient Roman silver treasure that was found in 1793 on the Esquiline Hill in Rome. The hoard is considered an important example of late antique silver work from the 4th century AD, probably about 380 for the major pieces. Since 1866, 57 objects, representing the great majority of the treasure, have been in the British Museum.

The Corbridge Lanx is the name of a Roman silver dish found near Corbridge, Northern England in 1735. Once part of a large Roman treasure, only the silver lanx remains from the original find. The British Museum eventually purchased it in 1993.

References

- 1 2 3 Lysons, Daniel; Lysons, Samuel (1817). "Antiquities: British and Roman". Magna Britannia Volume 5. pp. CCIII-CCXVIII. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- ↑ Dunlop, John Colin (1827). History of Roman Literature from its Earliest Periods to the Augustan Age. Eve Littel. New York. p. 233.

- ↑ Johns, Catherine; Painter, Kenneth (1991). "The Risley Park Lanx 'rediscovered'". Minerva2(6). pp. 6–13.

- 1 2 3 4 "The artful codgers: pensioners who conned British museums with £10m forgeries". London Evening Standard. 16 November 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Piggot, Stuart (1985). William Stukeley: an eighteenth-century antiquary. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 110.

- 1 2 Stukeley, William (1736). An account of a large silver plate, of antique basso relievo, Roman workmanship, found in Derbyshire, 1729. Read before the Antiquarian Society of London.

- 1 2 3 Henig, Martin (1996). The Art of Roman Britain. Routledge. p. 167. ISBN 0-415-15136-8

- ↑ Johns, Catherine. (1981). "The Risley Park Silver Lanx: A Lost Antiquity from Roman Britain". Antiquaries Journal Vol 61, Issue 1. pp. 53-72. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003581500029012

- 1 2 3 Flynn, Tom (Summer 2007). "Faking It" Archived 2 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine . Art Quarterly. Retrieved on 23 November 2007.

- 1 2 Middleton, Andrew; Lang, Janet (2005). Radiography of Cultural Material (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 181. ISBN 0-7506-6347-2

- ↑ Chadwick, Edward (17 November 2007). "Antiques rogues show: update 3". The Bolton News. Retrieved on 30 November 2007.

- ↑ Pallister, David (27 January 2008). "'The Antiques Rogue Show'". The Guardian.

- ↑ Kelly, James (16 November 2007). "Fraudsters who resented the art market". BBC News. Retrieved on 17 November 2007.