Related Research Articles

Turlough O'Carolan was a blind Celtic harper, composer and singer in Ireland whose great fame is due to his gift for melodic composition.

Irish music is music that has been created in various genres on the island of Ireland.

Granard is a town in the north of County Longford, Ireland, and has a traceable history going back to 236 CE. It is situated just south of the boundary between the watersheds of the Shannon and the Erne, at the point where the N55 national secondary road and the R194 regional road meet. It is 20 km north-east of Longford town. The barony of Granard is named for the town. The town is also in the civil parish of Granard.

Alice Letitia Milligan [pseud. Iris Olkyrn] was an Irish writer and activist in Ireland's Celtic Revival; an advocate for the political and cultural participation of women; and a Protestant-unionist convert to the cause of Irish independence. She was at the height of her renown at the turn of the 20th century when in Belfast, with Anna Johnston, she produced the political and literary monthly The Shan Van Vocht (1896–1899), and when in Dublin the Irish Literary Theatre's performed "The Last Feast of the Fianna” (1900), Milligan's interpretation of Celtic legend as national drama.

Prince of Wales was a transport ship in the First Fleet, assigned to transport convicts for the European colonisation of Australia. Accounts differ regarding her origins; she may have been built and launched in 1779 at Sidmouth, or in 1786 on the River Thames. Her First Fleet voyage commenced in 1787, with 47 female convicts aboard, and she arrived at Botany Bay in January 1788. On a difficult return voyage in 1788–1789 she became separated from her convoy and was found drifting helplessly off Rio de Janeiro with her crew incapacitated by scurvy.

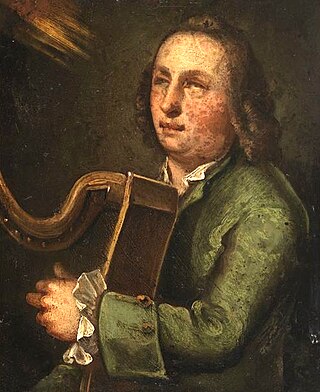

Thomas Connellan was an Irish harp player and composer.

"Give Me Your Hand" is a tune from early 17th century Ireland by Rory Dall O'Cahan. It is one of the most widely recorded pieces of Irish traditional music.

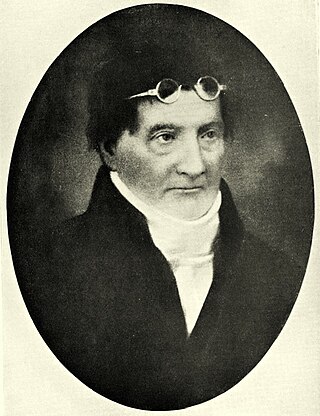

Edward Bunting was an Irish musician and folk music collector active in Belfast.

The Belfast Harp Festival, called by contemporary writers The Belfast Harpers Assembly, 11–14 July 1792, was a three-day musical and patriotic event organised in Belfast, Ireland, by leading members of the local Society for Promoting Knowledge : Dr. James MacDonnell, Robert Bradshaw, Henry Joy, and Robert Simms. Edward Bunting, a young classically trained organist, was commissioned to notate the forty tunes performed by ten harpists attending, work that was to form the major part of his General Collection of the Ancient Irish Music (1796). The venue of the contest was in The Assembly Room on Waring Street in Belfast which was opened as a market house in 1769.

Dominic Ó Mongáin, or Dominic Mungan, was an Irish harper and poet, born around 1715 in County Tyrone. The poem and air An raibh tú ag an gCarraig?, translated by Walsh as Have you been at Carrick?, has been attributed to him.

Patrick Byrne or Pádraig Dall Ó Beirn was the last noted exponent in Ireland of the historical Gaelic harp and the first Irish traditional musician to be photographed.

Charles Mongan Warburton was a 19th-century Anglican bishop who served two Irish Dioceses.

Hugh Higgins of Tyrawley was a blind Irish harper, 1737-after 1791.

Ruairí Dall Ó Catháin may have been an Irish harper and composer. Recent research, however, raises the question whether he ever really existed. He is said to have been born circa 1580 in County Antrim and to have died circa 1653 at Eglinton Castle.

Charles Fanning, Irish harper, born Foxford, County Mayo, 1736, died after 1792.

Arthur O'Neill was an Irish harper, a virtuoso player of the Irish harp or cláirseach: he was active during the final decades of its unbroken instrumental tradition in the later 18th and very early 19th century. He was closely associated with Edward Bunting, and the Belfast Harp Society's ultimately unsuccessful attempt to preserve the instrument, attending the Belfast Harper's Assembly and serving as the Society's harp tutor until 1813. He is best known for his lively and humorous memoir, collected by Bunting, which contained many reminiscences of famous harpers and of the environment in which they played.

The Coolin, or The Coolun, is an Irish air often characterised as one of the most beautiful in the traditional repertoire.

Charlotte Olivia Milligan Fox was an Irish composer, folk music collector and writer.

The Belfast Harp Society (1808-1813) and its successor, the Irish Harp Society (1819-1839), were philanthropic associations formed in the town of Belfast, Ireland, for the purpose of sustaining the music and tradition of itinerant Irish harpists, and secondarily, of promoting the study of the Irish language, history, and antiquities. For its patronage, the original society drew upon a diminishing circle of veterans of the patriotic and reform politics of the 1780s and '90s, among them several unrepentant United Irishmen. In its sectarian division, Belfast became increasingly hostile to Protestant interest in distinctive Irish culture. The society reconvened as the Irish Harp Society in 1819 only as a result of a large and belated subscription raised from expatriates in India. Once that source was exhausted, the new society ceased its activity.

References

- 1 2 Fox, Charlotte Milligan (1913). Annals of the Irish harpers. New York: E. P. Dutton & co. p. 125. hdl:2027/mdp.39015005067072. OCLC 3581446.

- 1 2 Flood, William H. Grattan (1905). "Harp Festivals and Harp Societies". A History of Irish Music. Browne and Nolan. OCLC 3557419.

- ↑ Fox, Charlotte Milligan (1913). Annals of the Irish harpers. New York: E. P. Dutton & co. p. 185. hdl:2027/mdp.39015005067072. OCLC 3581446.

- 1 2 3 Lanier, S.C. (1999). "'It is New-Strung and Shan't be Heard': Nationalism and Memory in the Irish Harp Tradition". British Journal of Ethnomusicology. 8: 1–26. doi:10.1080/09681229908567279. JSTOR 3060850.

- ↑ O'Neill, Francis (1913). "Harpers at the Granard and Belfast Meetings". Irish Minstrels and Musicians. The Regan Printing House. OCLC 4836421.

- 1 2 3 Fox, Charlotte Milligan (1913). Annals of the Irish harpers. New York: E. P. Dutton & co. p. 188. hdl:2027/mdp.39015005067072. OCLC 3581446.

- 1 2 Fox, Charlotte Milligan (1913). Annals of the Irish harpers. New York: E. P. Dutton & co. p. 131. hdl:2027/mdp.39015005067072. OCLC 3581446.