Related Research Articles

A medicine man or medicine woman is a traditional healer and spiritual leader who serves a community of Indigenous people of the Americas. Each culture has its own name in its language for spiritual healers and ceremonial leaders.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), Pub. L. 101-601, 25 U.S.C. 3001 et seq., 104 Stat. 3048, is a United States federal law enacted on November 16, 1990.

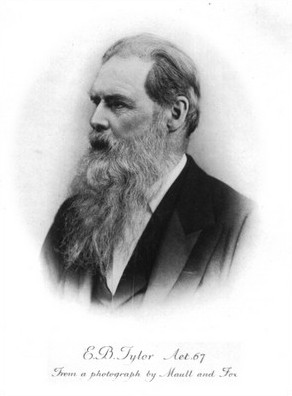

Anthropology of religion is the study of religion in relation to other social institutions, and the comparison of religious beliefs and practices across cultures. The anthropology of religion, as a field, overlaps with but is distinct from the field of Religious Studies. The history of anthropology of religion is a history of striving to understand how other people view and navigate the world. This history involves deciding what religion is, what it does, and how it functions. Today, one of the main concerns of anthropologists of religion is defining religion, which is a theoretical undertaking in and of itself. Scholars such as Edward Tylor, Emile Durkheim, E.E. Evans Pritchard, Mary Douglas, Victor Turner, Clifford Geertz, and Talal Asad have all grappled with defining and characterizing religion anthropologically.

Frank Hamilton Cushing was an American anthropologist and ethnologist. He made pioneering studies of the Zuni Indians of New Mexico by entering into their culture; his work helped establish participant observation as a common anthropological research strategy. In recent years, however, questions have emerged about Cushing's activities among the Zuni. Consequently, Frank Cushing's work provides an important case study for considering the ethics of both ethnographic research and the generation of museum collections.

Sir Edward Burnett Tylor was an English anthropologist, and professor of anthropology.

Economic anthropology is a field that attempts to explain human economic behavior in its widest historic, geographic and cultural scope. It is an amalgamation of economics and anthropology. It is practiced by anthropologists and has a complex relationship with the discipline of economics, of which it is highly critical. Its origins as a sub-field of anthropology began with work by the Polish founder of anthropology Bronislaw Malinowski and the French Marcel Mauss on the nature of reciprocity as an alternative to market exchange. For the most part, studies in economic anthropology focus on exchange.

Material culture is the aspect of culture manifested by the physical objects and architecture of a society. The term is primarily used in archaeology and anthropology, but is also of interest to sociology, geography and history. The field considers artifacts in relation to their specific cultural and historic contexts, communities and belief systems. It includes the usage, consumption, creation and trade of objects as well as the behaviors, norms and rituals that the objects create or take part in.

Morris Edward Opler, American anthropologist and advocate of Japanese American civil rights, was born in Buffalo, New York. He was the brother of Marvin Opler, an anthropologist and social psychiatrist.

History of anthropology in this article refers primarily to the 18th- and 19th-century precursors of modern anthropology. The term anthropology itself, innovated as a Neo-Latin scientific word during the Renaissance, has always meant "the study of man". The topics to be included and the terminology have varied historically. At present they are more elaborate than they were during the development of anthropology. For a presentation of modern social and cultural anthropology as they have developed in Britain, France, and North America since approximately 1900, see the relevant sections under Anthropology.

Salvage ethnography is the recording of the practices and folklore of cultures threatened with extinction, including as a result of modernization and assimilation. It is generally associated with the American anthropologist Franz Boas; he and his students aimed to record vanishing Native American cultures. Since the 1960s, anthropologists have used the term as part of a critique of 19th-century ethnography and early modern anthropology.

Spiro Mounds is an Indigenous archaeological site located in present-day eastern Oklahoma. The site was built by people from the Arkansas Valley Caddoan culture. that remains from an American Indian culture that was part of the major northern Caddoan Mississippian culture. The 80-acre site is located within a floodplain on the southern side of the Arkansas River. The modern town of Spiro developed approximately seven miles to the south.

The Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology is a museum affiliated with Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1866, the Peabody Museum is one of the oldest and largest museums focusing on anthropological material, with particular focus on the ethnography and archaeology of the Americas. The museum is caretaker to over 1.2 million objects, some 900 feet (270 m) of documents, 2,000 maps and site plans, and about 500,000 photographs. The museum is located at Divinity Avenue on the Harvard University campus. The museum is one of the four Harvard Museums of Science and Culture open to the public.

The Native American Church (NAC), also known as Peyotism and Peyote Religion, is a syncretic Native American religion that teaches a combination of traditional Native American beliefs and elements of Christianity, especially pertaining to the Ten Commandments, with sacramental use of the entheogen peyote. The religion originated in the Oklahoma Territory (1890–1907) in the late nineteenth century, after peyote was introduced to the southern Great Plains from Mexico. Today, it is the most widespread indigenous religion among Native Americans in the United States, Canada, and Mexico, with an estimated 300,000 adherents.

Indigenous archaeology is a sub-discipline of Western archaeological theory that seeks to engage and empower indigenous people in the preservation of their heritage and to correct perceived inequalities in modern archaeology. It also attempts to incorporate non-material elements of cultures, like oral traditions, into the wider historical narrative. This methodology came out of the global anti-colonial movements of the 1970s and 1980s led by aboriginal and indigenous people in settler-colonial nations, like the United States, Canada, and Australia. Major issues the sub-discipline attempts to address include the repatriation of indigenous remains to their respective peoples, the perceived biases that western archaeology's imperialistic roots have imparted into its modern practices, and the stewardship and preservation of indigenous people's cultures and heritage sites. This has encouraged the development of more collaborative relationships between archaeologists and indigenous people and has increased the involvement of indigenous people in archaeology and its related policies.

Two-spirit is a contemporary pan-Indian umbrella term used by some Indigenous North Americans to describe Native people who fulfill a traditional third-gender social role in their communities.

Ethnoscience has been defined as an attempt "to reconstitute what serves as science for others, their practices of looking after themselves and their bodies, their botanical knowledge, but also their forms of classification, of making connections, etc.".

The Yuquot Whalers' Shrine, previously located on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, was a site of purification rituals, passed down through the family of a Yuquot chief. It contained a collection of 88 carved human figures, four carved whale figures, and sixteen human skulls. Since the early twentieth century, it has been in the possession of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, but is rarely displayed. Talks are underway regarding repatriation.

Felix M. Keesing was a New Zealand-born anthropologist who specialized in the study of the Philippine Islands and the South Pacific. He came to the United States in the 1940s and taught at Stanford University, California, 1942–1961.

Florence Scundoo Shotridge was an Alaska Native ethnographer, museum educator, and weaver. From 1911 to 1917, she worked for the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. In 1905, she demonstrated Chilkat weaving at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon. In 1916, she co-directed with her husband Louis Shotridge a collecting expedition to Southeast Alaska that was funded by the retail magnate and Penn Museum trustee John Wanamaker.

The Indian burial ground trope is frequently used to explain supernatural events and hauntings in American popular culture. The trope gained popularity in the 1980s, making multiple appearances in horror film and television after its debut in The Amityville Horror (1979). Over time the Indian burial ground trope has become viewed as a cliche and in its current usage it commonly functions as a satirical element.

References

- 1 2 Hester, James J. (1968). "Pioneer Methods in Salvage Anthropology". Anthropological Quarterly. 41 (3): 132–146. doi:10.2307/3316788. JSTOR 3316788.

- ↑ Deloria, Philip Joseph (1998). Playing Indian. Yale University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-300-08067-4.

- 1 2 Beck, David R. M. (2010). "Collecting among the Menomini: Cultural Assault in Twentieth-Century Wisconsin". American Indian Quarterly. 34 (2): 157–193. doi:10.1353/aiq.0.0103. JSTOR 10.5250/amerindiquar.34.2.157. S2CID 161926576. Gale A224167268 Project MUSE 377359 ProQuest 216860994.

- ↑ Gulliford, Andrew (1992). "Curation and Repatriation of Sacred and Tribal Objects". The Public Historian. 14 (3): 23–38. doi:10.2307/3378225. JSTOR 3378225.

- 1 2 Niezen, Ronald (2000). "Bones and Spirits". Spirit Wars: Native North American Religions in the Age of Nation Building. University of California Press. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-0-520-21987-8.

- ↑ Weaver, Jace (1997). "Indian Presence with No Indians Present: NAGPRA and Its Discontents". Wíčazo Ša Review. 12 (2): 13–30. doi:10.2307/1409204. JSTOR 1409204.