The civil rights movement was a social movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement in the country. The movement had its origins in the Reconstruction era during the late 19th century and had its modern roots in the 1940s, although the movement made its largest legislative gains in the 1960s after years of direct actions and grassroots protests. The social movement's major nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience campaigns eventually secured new protections in federal law for the civil rights of all Americans.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Greensboro, North Carolina, and Nashville, Tennessee, the Committee sought to coordinate and assist direct-action challenges to the civic segregation and political exclusion of African Americans. From 1962, with the support of the Voter Education Project, SNCC committed to the registration and mobilization of black voters in the Deep South. Affiliates such as the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the Lowndes County Freedom Organization in Alabama also worked to increase the pressure on federal and state government to enforce constitutional protections.

Guy Hughes Carawan Jr. was an American folk musician and musicologist. He served as music director and song leader for the Highlander Research and Education Center in New Market, Tennessee.

James Morris Lawson Jr. is an American activist and university professor. He was a leading theoretician and tactician of nonviolence within the Civil Rights Movement. During the 1960s, he served as a mentor to the Nashville Student Movement and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He was expelled from Vanderbilt University for his civil rights activism in 1960, and later served as a pastor in Los Angeles for 25 years.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civil rights movement.

Lawrence Guyot Jr. was an American civil rights activist and the director of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in 1964.

Diane Judith Nash is an American civil rights activist, and a leader and strategist of the student wing of the Civil Rights Movement.

James Luther Bevel was an American minister and leader of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement in the United States. As a member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and then as its Director of Direct Action and Nonviolent Education, Bevel initiated, strategized, and developed SCLC's three major successes of the era: the 1963 Birmingham Children's Crusade, the 1965 Selma voting rights movement, and the 1966 Chicago open housing movement. He suggested that SCLC call for and join a March on Washington in 1963. Bevel strategized the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches, which contributed to Congressional passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Doris Adelaide Derby was an American activist and documentary photographer. She was the adjunct associate professor of anthropology at Georgia State University and the founding director of their Office of African-American Student Services and Programs. She was active in the Mississippi civil rights movement, and her work discusses the themes of race and African-American identity. She was a working member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and co-founder of the Free Southern Theater. Her photography has been exhibited internationally. Two of her photographs were published in Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, to which she also contributed an essay about her experiences in the Mississippi civil rights movement.

The Freedom Singers originated as a quartet formed in 1962 at Albany State College in Albany, Georgia. After folk singer Pete Seeger witnessed the power of their congregational-style of singing, which fused black Baptist a cappella church singing with popular music at the time, as well as protest songs and chants. Churches were considered to be safe spaces, acting as a shelter from the racism of the outside world. As a result, churches paved the way for the creation of the freedom song. After witnessing the influence of freedom songs, Seeger suggested The Freedom Singers as a touring group to the SNCC executive secretary James Forman as a way to fuel future campaigns. Intrinsically connected, their performances drew aid and support to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the emerging civil rights movement. As a result, communal song became essential to empowering and educating audiences about civil rights issues and a powerful social weapon of influence in the fight against Jim Crow segregation. Rutha Mae Harris, a former freedom singer, speculated that without the music force of broad communal singing, the civil rights movement may not have resonated beyond of the struggles of the Jim Crow South. Their most notable song “We Shall Not Be Moved” translated from the original Freedom Singers to the second generation of Freedom Singers, and finally to the Freedom Voices, made up of field secretaries from SNCC. "We Shall Not Be Moved" is considered by many to be the "face" of the Civil Rights movement. Rutha Mae Harris, a former freedom singer, speculated that without the music force of broad communal singing, the civil rights movement may not have resonated beyond of the struggles of the Jim Crow South. Since the Freedom Singers were so successful, a second group was created called the Freedom Voices.

Bernard Lafayette, Jr. is an American civil rights activist and organizer, who was a leader in the Civil Rights Movement. He played a leading role in early organizing of the Selma Voting Rights Movement; was a member of the Nashville Student Movement; and worked closely throughout the 1960s movements with groups such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the American Friends Service Committee.

Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions Morgan v. Virginia (1946) and Boynton v. Virginia (1960), which ruled that segregated public buses were unconstitutional. The Southern states had ignored the rulings and the federal government did nothing to enforce them. The first Freedom Ride left Washington, D.C., on May 4, 1961, and was scheduled to arrive in New Orleans on May 17.

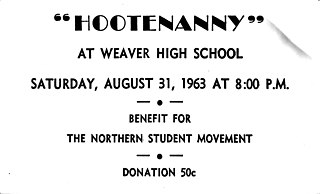

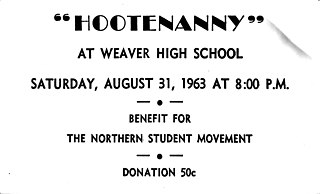

The Northern Student Movement (NSM) was an American civil rights organization that drew inspiration from sit-ins and lunch counter protests led by students in the south. NSM was founded at Yale University in 1961 by Peter J. Countryman, which grew out of the work of a committee formed by the New England Student Christian Movement, and was affiliated with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Countryman began NSM's work by collecting books for a predominantly African-American college and raising funds for SNCC. He then turned to organizing tutoring programs for inner city youth in northeastern cities. By 1963, NSM was reported to be helping as many as 3,500 children using 2,200 student volunteers from 50 colleges and universities. NSM also encouraged direct-action protests, sending volunteers to sit-ins in the South and organizing rent strikes in the North. In the early 60's, NSM's work was divided into three areas which were each headed by an executive committee: "the campus, the community, and the south."

James Zwerg is an American retired minister who was involved with the Freedom Riders in the early 1960s.

William E. Harbour was an American civil rights activist who participated in the Freedom Rides. He was one of several youth activists involved in the latter actions, along with John Lewis, William Barbee, Paul Brooks, Charles Butler, Allen Cason, Catherine Burks, and Lucretia Collins.

Judy Richardson is an American documentary filmmaker and civil rights activist. She was Distinguished Visiting Lecturer of Africana Studies at Brown University.

The Mississippi Freedom Project (MFP) is an archive of oral histories collected by the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at the University of Florida. The ongoing project contains 100+ interviews online and focuses on interviews with civil rights veterans and notable residents of the Mississippi Delta. The collection centers on activism and organizing in partnership with the Sunflower County Civil Rights Organization in Sunflower, Mississippi.

This is a timeline of the civil rights movement in the United States, a nonviolent mid-20th century freedom movement to gain legal equality and the enforcement of constitutional rights for people of color. The goals of the movement included securing equal protection under the law, ending legally institutionalized racial discrimination, and gaining equal access to public facilities, education reform, fair housing, and the ability to vote.

Oretha Castle Haley was an American civil rights activist in New Orleans where she challenged the segregation of facilities and promoted voter registration. She came from a working-class background, yet was able to enroll in the Southern University of New Orleans, SUNO, then a center of student activism. She joined the protest marches and went on to become a prominent activist in the Civil Rights Movement.

Carolanne Marie "Candie" Carawan (née Anderson) is an American civil rights activist, singer and author known for popularizing the protest song "We Shall Overcome" to the American Civil Rights Movement with her husband Guy Carawan in the 1960s.