In organic chemistry, an alkane, or paraffin, is an acyclic saturated hydrocarbon. In other words, an alkane consists of hydrogen and carbon atoms arranged in a tree structure in which all the carbon–carbon bonds are single. Alkanes have the general chemical formula CnH2n+2. The alkanes range in complexity from the simplest case of methane, where n = 1, to arbitrarily large and complex molecules, like pentacontane or 6-ethyl-2-methyl-5-(1-methylethyl) octane, an isomer of tetradecane.

In organic chemistry, an alkene, or olefin, is a hydrocarbon containing a carbon–carbon double bond. The double bond may be internal or in the terminal position. Terminal alkenes are also known as α-olefins.

In organic chemistry, an alkyne is an unsaturated hydrocarbon containing at least one carbon—carbon triple bond. The simplest acyclic alkynes with only one triple bond and no other functional groups form a homologous series with the general chemical formula CnH2n−2. Alkynes are traditionally known as acetylenes, although the name acetylene also refers specifically to C2H2, known formally as ethyne using IUPAC nomenclature. Like other hydrocarbons, alkynes are generally hydrophobic.

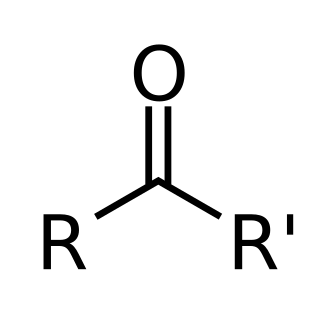

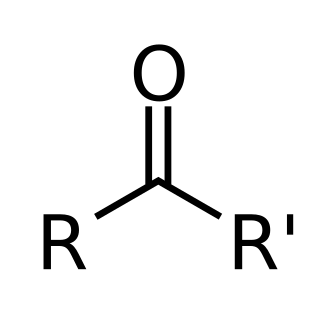

In organic chemistry, a ketone is an organic compound with the structure R−C(=O)−R', where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group −C(=O)−. The simplest ketone is acetone, with the formula (CH3)2CO. Many ketones are of great importance in biology and in industry. Examples include many sugars (ketoses), many steroids, and the solvent acetone.

The haloalkanes are alkanes containing one or more halogen substituents. They are a subset of the general class of halocarbons, although the distinction is not often made. Haloalkanes are widely used commercially. They are used as flame retardants, fire extinguishants, refrigerants, propellants, solvents, and pharmaceuticals. Subsequent to the widespread use in commerce, many halocarbons have also been shown to be serious pollutants and toxins. For example, the chlorofluorocarbons have been shown to lead to ozone depletion. Methyl bromide is a controversial fumigant. Only haloalkanes that contain chlorine, bromine, and iodine are a threat to the ozone layer, but fluorinated volatile haloalkanes in theory may have activity as greenhouse gases. Methyl iodide, a naturally occurring substance, however, does not have ozone-depleting properties and the United States Environmental Protection Agency has designated the compound a non-ozone layer depleter. For more information, see Halomethane. Haloalkane or alkyl halides are the compounds which have the general formula "RX" where R is an alkyl or substituted alkyl group and X is a halogen.

In organic chemistry, the cycloalkanes are the monocyclic saturated hydrocarbons. In other words, a cycloalkane consists only of hydrogen and carbon atoms arranged in a structure containing a single ring, and all of the carbon-carbon bonds are single. The larger cycloalkanes, with more than 20 carbon atoms are typically called cycloparaffins. All cycloalkanes are isomers of alkenes.

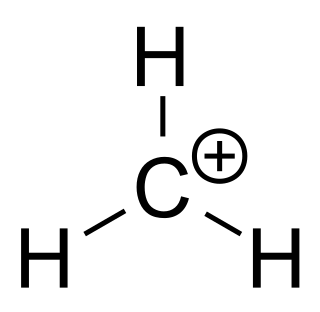

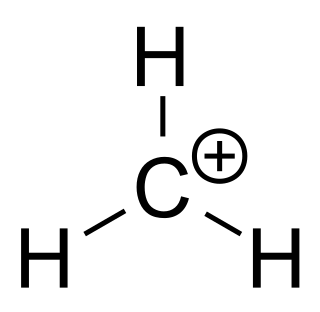

A carbocation is an ion with a positively charged carbon atom. Among the simplest examples are the methenium CH+

3, methanium CH+

5 and vinyl C

2H+

3 cations. Occasionally, carbocations that bear more than one positively charged carbon atom are also encountered.

In organic chemistry, an alkyl group is an alkane missing one hydrogen. The term alkyl is intentionally unspecific to include many possible substitutions. An acyclic alkyl has the general formula of −CnH2n+1. A cycloalkyl group is derived from a cycloalkane by removal of a hydrogen atom from a ring and has the general formula −CnH2n−1. Typically an alkyl is a part of a larger molecule. In structural formulae, the symbol R is used to designate a generic (unspecified) alkyl group. The smallest alkyl group is methyl, with the formula −CH3.

Cyclopropane is the cycloalkane with the molecular formula (CH2)3, consisting of three methylene groups (CH2) linked to each other to form a triangular ring. The small size of the ring creates substantial ring strain in the structure. Cyclopropane itself is mainly of theoretical interest but many of its derivatives - cyclopropanes - are of commercial or biological significance.

In organic chemistry, an alicyclic compound contains one or more all-carbon rings which may be either saturated or unsaturated, but do not have aromatic character. Alicyclic compounds may have one or more aliphatic side chains attached.

In chemical nomenclature, the IUPAC nomenclature of organic chemistry is a method of naming organic chemical compounds as recommended by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC). It is published in the Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry. Ideally, every possible organic compound should have a name from which an unambiguous structural formula can be created. There is also an IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry.

In chemistry, conformational isomerism is a form of stereoisomerism in which the isomers can be interconverted just by rotations about formally single bonds. While any two arrangements of atoms in a molecule that differ by rotation about single bonds can be referred to as different conformations, conformations that correspond to local minima on the potential energy surface are specifically called conformational isomers or conformers. Conformations that correspond to local maxima on the energy surface are the transition states between the local-minimum conformational isomers. Rotations about single bonds involve overcoming a rotational energy barrier to interconvert one conformer to another. If the energy barrier is low, there is free rotation and a sample of the compound exists as a rapidly equilibrating mixture of multiple conformers; if the energy barrier is high enough then there is restricted rotation, a molecule may exist for a relatively long time period as a stable rotational isomer or rotamer. When the time scale for interconversion is long enough for isolation of individual rotamers, the isomers are termed atropisomers. The ring-flip of substituted cyclohexanes constitutes another common form of conformational isomerism.

In organic chemistry, a rearrangement reaction is a broad class of organic reactions where the carbon skeleton of a molecule is rearranged to give a structural isomer of the original molecule. Often a substituent moves from one atom to another atom in the same molecule, hence these reactions are usually intramolecular. In the example below, the substituent R moves from carbon atom 1 to carbon atom 2:

Magic acid (FSO3H·SbF5) is a superacid consisting of a mixture, most commonly in a 1:1 molar ratio, of fluorosulfuric acid (HSO3F) and antimony pentafluoride (SbF5). This conjugate Brønsted–Lewis superacid system was developed in the 1960s by the George Olah lab at Case Western Reserve University, and has been used to stabilize carbocations and hypercoordinated carbonium ions in liquid media. Magic acid and other superacids are also used to catalyze isomerization of saturated hydrocarbons, and have been shown to protonate even weak bases, including methane, xenon, halogens, and molecular hydrogen.

Higher alkanes are alkanes having nine or more carbon atoms. Nonane is the lightest alkane to have a flash point above 25 °C, and is not classified as dangerously flammable.

A quaternary carbon is a carbon atom bound to four other carbon atoms. For this reason, quaternary carbon atoms are found only in hydrocarbons having at least five carbon atoms. Quaternary carbon atoms can occur in branched alkanes, but not in linear alkanes.

A tertiary carbon atom is a carbon atom bound to three other carbon atoms. For this reason, tertiary carbon atoms are found only in hydrocarbons containing at least four carbon atoms. They are called saturated hydrocarbons because they only contain carbon-carbon single bonds. Tertiary carbons have a hybridization of sp3. Tertiary carbon atoms can occur, for example, in branched alkanes, but not in linear alkanes.

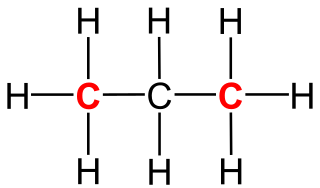

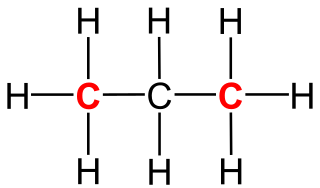

In organic chemistry, a primary carbon is a carbon atom which is bound to only one other carbon atom. It is thus at the end of a carbon chain. In case of an alkane, three hydrogen atoms are bound to a primary carbon. A hydrogen atom could also be replaced by a hydroxy group, which would make the molecule a primary alcohol.

Group 14 hydrides are chemical compounds composed of hydrogen atoms and group 14 atoms.

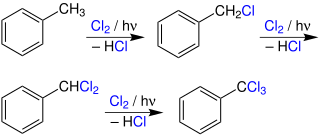

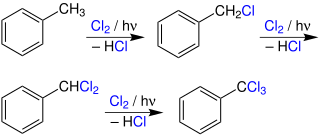

Photochlorination is a chlorination reaction that is initiated by light. Usually a C-H bond is converted to a C-Cl bond. Photochlorination is carried out on an industrial scale. The process is exothermic and proceeds as a chain reaction initiated by the homolytic cleavage of molecular chlorine into chlorine radicals by ultraviolet radiation. Many chlorinated solvents are produced in this way.