Related Research Articles

An appropriation bill, also known as supply bill or spending bill, is a proposed law that authorizes the expenditure of government funds. It is a bill that sets money aside for specific spending. In some democracies, approval of the legislature is necessary for the government to spend money.

The welfare state of the United Kingdom began to evolve in the 1900s and early 1910s, and comprises expenditures by the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland intended to improve health, education, employment and social security. The British system has been classified as a liberal welfare state system.

Welfare spending is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifically to social insurance programs which provide support only to those who have previously contributed, as opposed to social assistance programs which provide support on the basis of need alone. The International Labour Organization defines social security as covering support for those in old age, support for the maintenance of children, medical treatment, parental and sick leave, unemployment and disability benefits, and support for sufferers of occupational injury.

The Fair Deal was a set of proposals put forward by U.S. President Harry S. Truman to Congress in 1945 and in his January 1949 State of the Union Address. More generally, the term characterizes the entire domestic agenda of the Truman administration, from 1945 to 1953. It offered new proposals to continue New Deal liberalism, but with a conservative coalition controlling Congress, only a few of its major initiatives became law and then only if they had considerable Republican Party support. As Richard Neustadt concludes, the most important proposals were aid to education, national health insurance, the Fair Employment Practices Commission, and repeal of the Taft–Hartley Act. They were all debated at length, then voted down. Nevertheless, enough smaller and less controversial items passed that liberals could claim some success.

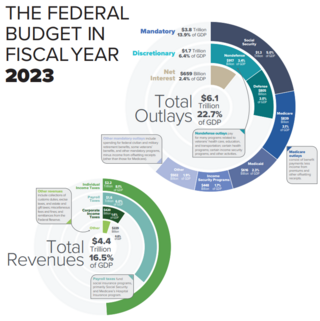

The United States budget comprises the spending and revenues of the U.S. federal government. The budget is the financial representation of the priorities of the government, reflecting historical debates and competing economic philosophies. The government primarily spends on healthcare, retirement, and defense programs. The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office provides extensive analysis of the budget and its economic effects. CBO estimated in February 2024 that Federal debt held by the public is projected to rise from 99 percent of GDP in 2024 to 116 percent in 2034 and would continue to grow if current laws generally remained unchanged. Over that period, the growth of interest costs and mandatory spending outpaces the growth of revenues and the economy, driving up debt. Those factors persist beyond 2034, pushing federal debt higher still, to 172 percent of GDP in 2054.

It's Time was a political campaign run by the Australian Labor Party (ALP) under Gough Whitlam during the 1972 federal election in Australia. Campaigning on the perceived need for change after 23 years of conservative government, Labor put forward a raft of major policy proposals, accompanied by a television advertising campaign of prominent celebrities singing a jingle entitled It's Time. It was ultimately successful, as Labor picked up eight seats and won a majority. This was the first time Labor had been in government since it lost the 1949 federal election to the Liberal Party.

The Fourth Labour Government of New Zealand governed New Zealand from 26 July 1984 to 2 November 1990. It was the first Labour government to win a second consecutive term since the First Labour Government of 1935 to 1949. The policy agenda of the Fourth Labour Government differed significantly from that of previous Labour governments: it enacted major social reforms and economic reforms.

The Third Labour Government of New Zealand was the government of New Zealand from 1972 to 1975. During its time in office, it carried out a wide range of reforms in areas such as overseas trade, farming, public works, energy generation, local government, health, the arts, sport and recreation, regional development, environmental protection, education, housing, and social welfare. Māori also benefited from revisions to the laws relating to land, together with a significant increase in a Māori and Island Affairs building programme. In addition, the government encouraged biculturalism and a sense of New Zealand identity. However, the government damaged relations between Pākehā and Pasifika New Zealanders by instituting the Dawn Raids on alleged overstayers from the Pacific Islands; the raids have been described as "the most blatantly racist attack on Pacific peoples by the New Zealand government in New Zealand’s history". The government lasted for one term before being defeated a year after the death of its popular leader, Norman Kirk.

The United States federal budget is divided into three categories: mandatory spending, discretionary spending, and interest on debt. Also known as entitlement spending, in US fiscal policy, mandatory spending is government spending on certain programs that are required by law. Congress established mandatory programs under authorization laws. Congress legislates spending for mandatory programs outside of the annual appropriations bill process. Congress can only reduce the funding for programs by changing the authorization law itself. This normally requires a 60-vote majority in the Senate to pass. Discretionary spending on the other hand will not occur unless Congress acts each year to provide the funding through an appropriations bill. Expenditure is often influenced by Federal Reserve advisory.

Social security, in Australia, refers to a system of social welfare payments provided by Australian Government to eligible Australian citizens, permanent residents, and limited international visitors. These payments are almost always administered by Centrelink, a program of Services Australia. In Australia, most payments are means tested.

India has a robust social security legislative framework governing social security, encompassing multiple labour laws and regulations. These laws govern various aspects of social security, particularly focusing on the welfare of the workforce. The primary objective of these measures is to foster sound industrial relations, cultivate a high-quality work environment, ensure legislative compliance, and mitigate risks such as accidents and health concerns. Moreover, social security initiatives aim to safeguard against social risks such as retirement, maternity, healthcare and unemployment while tax-funded social assistance aims to reduce inequalities and poverty. The Directive Principles of State Policy, enshrined in Part IV of the Indian Constitution reflects that India is a welfare state. Food security to all Indians are guaranteed under the National Food Security Act, 2013 where the government provides highly subsidised food grains or a food security allowance to economically vulnerable people. The system has since been universalised with the passing of The Code on Social Security, 2020. These cover most of the Indian population with social protection in various situations in their lives.

Social security is divided by the French government into five branches: illness; old age/retirement; family; work accident; and occupational disease. From an institutional point of view, French social security is made up of diverse organismes. The system is divided into three main Regimes: the General Regime, the Farm Regime, and the Self-employed Regime. In addition there are numerous special regimes dating from prior to the creation of the state system in the mid-to-late 1940s.

Welfare in France includes all systems whose purpose is to protect people against the financial consequences of social risks.

In the United States, the federal and state social programs including cash assistance, health insurance, food assistance, housing subsidies, energy and utilities subsidies, and education and childcare assistance. Similar benefits are sometimes provided by the private sector either through policy mandates or on a voluntary basis. Employer-sponsored health insurance is an example of this.

Social security or welfare in Finland is very comprehensive compared to what almost all other countries provide. In the late 1980s, Finland had one of the world's most advanced welfare systems, which guaranteed decent living conditions to all Finns. Created almost entirely during the first three decades after World War II, the social security system was an outgrowth of the traditional Nordic belief that the state is not inherently hostile to the well-being of its citizens and can intervene benevolently on their behalf. According to some social historians, the basis of this belief was a relatively benign history that had allowed the gradual emergence of a free and independent peasantry in the Nordic countries and had curtailed the dominance of the nobility and the subsequent formation of a powerful right wing. Finland's history was harsher than the histories of the other Nordic countries but didn't prevent the country from following their path of social development.

The United States federal budget consists of mandatory expenditures, discretionary spending for defense, Cabinet departments and agencies, and interest payments on debt. This is currently over half of U.S. government spending, the remainder coming from state and local governments.

The Welfare Reform Act 2012 is an Act of Parliament in the United Kingdom which makes changes to the rules concerning a number of benefits offered within the British social security system. It was enacted by the Parliament of the United Kingdom on 8 March 2012.

The Essential Living Fund (ELF) is a local welfare assistance scheme in Essex, England that was introduced in April 2013 following the abolition of the discretionary element of the Social Fund. It replaces two discretionary elements of the Social Fund - crisis loans and community care grants. Under the old system these payments were administered by the Department for Work and Pensions but ELFs are now administered by local government. According to Citizens Advice literature ELFs are "designed to ease exceptional pressure on people and their families". However, these benefits are not in the form of currency and are distributed using indirect methods such as: Use of food vouchers or supermarket vouchers, use of AllPay cards, provision of recycled furniture from reputable charity, and provision of white goods from a reputable local dealer. These indirect methods reduce the control participating individuals have over what they buy.

Social Security Scotland is an executive agency of the Scottish Government with responsibility for social security provision.

The Minister for Work and Pensions, or Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Work and Pensions in the House of Lords, is a junior position in the Department for Work and Pensions in the British government. It is currently held by The Viscount Younger of Leckie, who took the office on 1 January 2023.

References

- ↑ Welfare Reform Act 2012, ss.70-73.

- ↑ House of Commons Library (2012) Localisation of the Social Fund, Standard Note: SN06413, Steven Kennedy, Social policy section. Available at: Parliament website (accessed 7 November 2012).

- ↑ The Office of Social Fund Commissioner is also abolished in April 2013. See Welfare Reform Act 2012, s.70.

- ↑ See Buck,T et al (2009) The Social Fund: Law and Practice, third edition (London: Sweet & Maxwell), which contains comprehensive annotations to all the social fund directions.

- ↑ Green Paper: Vol.1, Reform of Social Security, HMSO, 1985. Cmnd.9517; Vol.2, Programme for Change, HMSO, 1985. Cmnd.9518; Vol.3, Background Papers, HMSO, 1985. Cmnd.9519.

- ↑ Reform of Social Security — Programme for Action, HMSO, 1985. Cmnd.9691.

- ↑ ss. 32-35.

- ↑ Council on Tribunals, Special Report, Social Security - Abolition of independent appeals under the proposed Social Fund, HMSO, 1986, Cmnd.9722.

- ↑ Social Security Act 1986, s.35.

- ↑ SSAC, Report on the Draft Social Fund Manual (1987).

- ↑ See Social Fund Direction 4

- ↑ The Social Fund Guide contains all the relevant Social Fund Directions and Guidance. See: http://www.dwp.gov.uk/docs/social-fund-guide.pdf (accessed 30 November 2012).

- ↑ Social Fund Direction 2.

- ↑ See Buck,T et al. (2009) The Social Fund: Law and Practice, third edition (London: Sweet & Maxwell), pp. 126-134.

- ↑ Direction 3

- ↑ See Buck T (2009) The Social Fund: Law & Practice (London: Sweet & Maxwell), pp. 88-89.

- ↑ House of Commons Library (2012) Localisation of the Social Fund, Standard Note: SN06413, Steven Kennedy, Social policy section. Available at: Parliament website (accessed 7 November 2012).

- ↑ See < "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-15. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)> (accessed 27 November 2012). - ↑ IRS website: <http://www.irs-review.org.uk/sfreform/sfreform.htm> (accessed 27 November 2012).

- ↑ House of Commons Library (2012) Localisation of the Social Fund, Standard Note: SN06413, Steven Kennedy, Social policy section. Available at: Parliament website (accessed 7 November 2012).

Bibliography

Buck,T et al. (2009) The Social Fund: Law and Practice, third edition (London: Sweet & Maxwell).

Grover, C (2011) The social fund 20 years on: historical and policy aspects of loaning social security (Farnham: Ashgate).

Grover, C (2012) Abolishing the discretionary Social Fund: continuity and change in relieving ‘special expenses’. Journal of Social Security Law, 19 (1). pp. 12–28.

House of Commons Library (2012) Localisation of the Social Fund, Standard Note: SN06413, Steven Kennedy, Social policy section. Available at: Parliament website (accessed 7 November 2012).