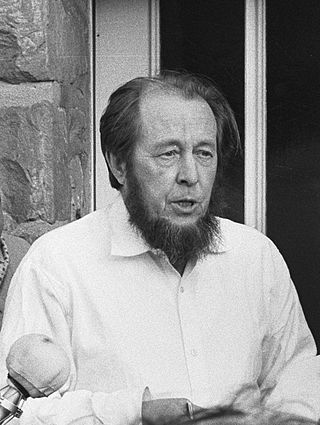

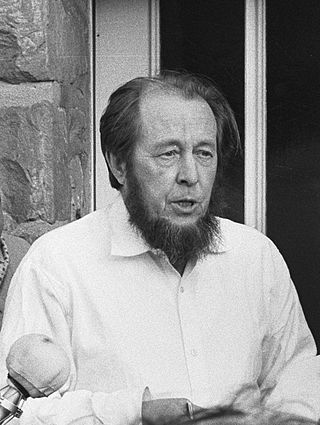

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn was a Russian writer and prominent Soviet dissident who helped to raise global awareness of political repression in the Soviet Union, especially the Gulag prison system.

The Gulag was a system of forced labor camps in the Soviet Union. The word Gulag originally referred only to the division of the Soviet secret police that was in charge of running the forced labor camps from the 1930s to the early 1950s during Joseph Stalin's rule, but in English literature the term is popularly used for the system of forced labor throughout the Soviet era. The abbreviation GULAG (ГУЛАГ) stands for "Гла́вное Управле́ние исправи́тельно-трудовы́х ЛАГере́й", but the full official name of the agency changed several times.

Samizdat was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the documents from reader to reader. The practice of manual reproduction was widespread, because typewriters and printing devices required official registration and permission to access. This was a grassroots practice used to evade official Soviet censorship.

The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation is a three-volume non-fiction series written between 1958 and 1968 by Russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, a Soviet dissident. It was first published in 1973 by the Parisian publisher YMCA-Press, and it was translated into English and French the following year. It explores a vision of life in what is often known as the Gulag, the Soviet labour camp system. Solzhenitsyn constructed his highly detailed narrative from various sources including reports, interviews, statements, diaries, legal documents, and his own experience as a Gulag prisoner.

Butyrskaya prison, usually known simply as Butyrka, is a prison in the Tverskoy District of central Moscow, Russia. In Imperial Russia it served as the central transit prison. During the Soviet Union era (1917–1991) it held many political prisoners. As of 2022 Butyrka remains the largest of Moscow's remand prisons. Overcrowding is an ongoing problem.

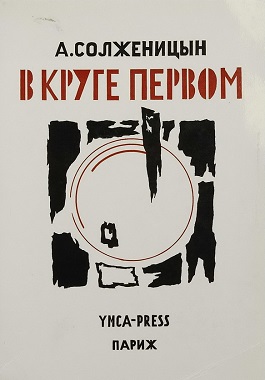

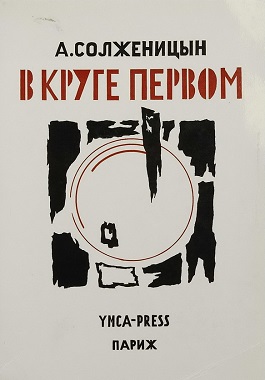

In the First Circle is a novel by Russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, released in 1968. A more complete version of the book was published in English in 2009.

Katorga was a system of penal labor in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union.

Lev Zalmanovich (Zinovyevich) Kopelev was a Soviet author and dissident.

Yevgenia Solomonovna Ginzburg was a Soviet writer who served an 18-year sentence in the Kolyma Gulag. Her given name is often Latinized to Eugenia.

Alexander "Alik" Ilyich Ginzburg, was a Russian journalist, poet, human rights activist and dissident. Between 1961 and 1969 he was sentenced three times to labor camps. In 1979, Ginzburg was released and expelled to the United States, along with four other political prisoners and their families, as part of a prisoner exchange.

Soviet dissidents were people who disagreed with certain features of Soviet ideology or with its entirety and who were willing to speak out against them. The term dissident was used in the Soviet Union (USSR) in the period from the mid-1960s until the Fall of Communism. It was used to refer to small groups of marginalized intellectuals whose challenges, from modest to radical to the Soviet regime, met protection and encouragement from correspondents, and typically criminal prosecution or other forms of silencing by the authorities. Following the etymology of the term, a dissident is considered to "sit apart" from the regime. As dissenters began self-identifying as dissidents, the term came to refer to an individual whose non-conformism was perceived to be for the good of a society. The most influential subset of the dissidents is known as the Soviet human rights movement.

The Vorkuta Uprising was a major uprising of forced labor camp inmates at the Rechlag Gulag special labor camp in Vorkuta, Russian SFSR, USSR from 19 July to 1 August 1953, shortly after the arrest of Lavrentiy Beria. The uprising was violently stopped by the camp administration after two weeks of bloodless standoff.

Nikolai Ivanovich Getman or Mykola Ivanovich Hetman, an artist, was born in 1917 in Kharkiv, Ukraine, and died at his home in Orel, Russia, in August 2004. He was a prisoner from 1946 to 1953 in forced labor camps in Siberia and Kolyma, where he survived as a result of his ability to sketch for the propaganda requirements of the authorities. He is remembered as one of few artists who has recorded the life of prisoners in the Gulag in the form of paintings.

Sukhanovka, short for Sukhanovskaya osoborezhimnaya tyur'ma 'Sukhanovo special-regime prison,' was a prison established by the NKVD under N. I. Yezhov in 1938 for "particularly dangerous enemies of the people" on the grounds of the old Ekaterinskaia Pustyn' Monastery near Vidnoye, just south of Moscow. Known officially as Special Object 110, it was said to be worse than the Lubyanka, Lefortovo, or Butyrka prisons in Moscow itself. From 1958 it was a jail hospital. During 1992 the prison was returned to the church as a monastery and on November 17, 1992, the first vows were made within its walls.

Art and culture took on a variety of forms in the forced labor camps of the Gulag system that existed across the Soviet Union during the first half of the twentieth century. Theater, music, visual art, and literature played a role in camp life for many of the millions of prisoners who passed through the Gulag system. Some creative endeavors were initiated and executed by prisoners themselves, while others were overseen by the camp administration. Some projects benefited from prisoners who had been professional artists; others were organized by amateurs. The robust presence of the arts in the Gulag camps is a testament to the resourcefulness and resilience of prisoners there, many of whom derived material benefits and psychological comfort from their involvement in artistic projects.

Alexander Pavlovich Lavut was a mathematician, dissident and a key figure in the civil rights movement in the Soviet Union.

The Initiative or Action Group for the Defense of Human Rights in the USSR was the first civic organization of the Soviet human rights movement. Founded in 1969 by 15 dissidents, the unsanctioned group functioned for over six years as a public platform for Soviet dissidents concerned with violations of human rights in the Soviet Union.

In 1965 a human rights movement emerged in the USSR. Those actively involved did not share a single set of beliefs. Many wanted a variety of civil rights — freedom of expression, of religious belief, of national self-determination. To some it was crucial to provide a truthful record of what was happening in the country, not the heavily censored version provided in official media outlets. Others still were "reform Communists" who thought it possible to change the Soviet system for the better.

Alexey Gennadievich Nechayev is a Russian entrepreneur and politician, president of the Russian cosmetics company Faberlic, a member of the All-Russia People's Front, chairman of the New People political party since 8 August 2020.

The 1970 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to the Russian novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008) "for the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature." For political reasons he would not receive the prize until 1974. Solzhenitsyn is the fourth Russian recipient of the prize after Ivan Bunin in 1933, Boris Pasternak in 1958 and Mikhail Sholokhov in 1965.