Hang gliding is an air sport or recreational activity in which a pilot flies a light, non-motorised, heavier-than-air aircraft called a hang glider. Most modern hang gliders are made of an aluminium alloy or composite frame covered with synthetic sailcloth to form a wing. Typically the pilot is in a harness suspended from the airframe, and controls the aircraft by shifting body weight in opposition to a control frame.

Paragliding is the recreational and competitive adventure sport of flying paragliders: lightweight, free-flying, foot-launched glider aircraft with no rigid primary structure. The pilot sits in a harness or in a cocoon-like 'pod' suspended below a fabric wing. Wing shape is maintained by the suspension lines, the pressure of air entering vents in the front of the wing, and the aerodynamic forces of the air flowing over the outside.

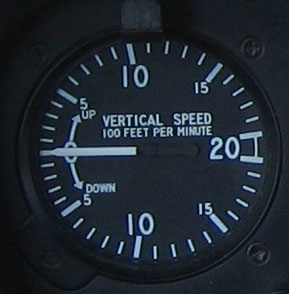

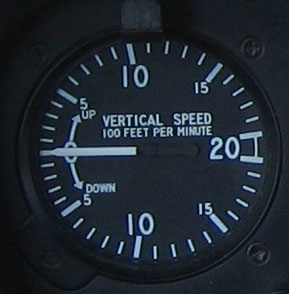

In aviation, a variometer – also known as a rate of climb and descent indicator (RCDI), rate-of-climb indicator, vertical speed indicator (VSI), or vertical velocity indicator (VVI) – is one of the flight instruments in an aircraft used to inform the pilot of the rate of descent or climb. It can be calibrated in metres per second, feet per minute or knots, depending on country and type of aircraft. It is typically connected to the aircraft's external static pressure source.

In aerodynamics, the lift-to-drag ratio is the lift generated by an aerodynamic body such as an aerofoil or aircraft, divided by the aerodynamic drag caused by moving through air. It describes the aerodynamic efficiency under given flight conditions. The L/D ratio for any given body will vary according to these flight conditions.

Dynamic soaring is a flying technique used to gain energy by repeatedly crossing the boundary between air masses of different velocity. Such zones of wind gradient are generally found close to obstacles and close to the surface, so the technique is mainly of use to birds and operators of radio-controlled gliders, but glider pilots are sometimes able to soar dynamically in meteorological wind shears at higher altitudes.

In aeronautics, the rate of climb (RoC) is an aircraft's vertical speed, that is the positive or negative rate of altitude change with respect to time. In most ICAO member countries, even in otherwise metric countries, this is usually expressed in feet per minute (ft/min); elsewhere, it is commonly expressed in metres per second (m/s). The RoC in an aircraft is indicated with a vertical speed indicator (VSI) or instantaneous vertical speed indicator (IVSI).

Some of the pilots in the sport of gliding take part in gliding competitions. These are usually racing competitions, but there are also aerobatic contests and on-line league tables.

The Schempp-Hirth Mini Nimbus is a 15 Metre-class glider designed and built by Schempp-Hirth GmbH in the late 1970s.

The ASK 21 is a glass-reinforced plastic (GRP) two-seat glider aircraft with a T-tail. The ASK 21 is designed primarily for beginner instruction, but is also suitable for cross-country flying and aerobatic instruction.

Gliding flight is heavier-than-air flight without the use of thrust; the term volplaning also refers to this mode of flight in animals. It is employed by gliding animals and by aircraft such as gliders. This mode of flight involves flying a significant distance horizontally compared to its descent and therefore can be distinguished from a mostly straight downward descent like a round parachute.

A glider is a fixed-wing aircraft that is supported in flight by the dynamic reaction of the air against its lifting surfaces, and whose free flight does not depend on an engine. Most gliders do not have an engine, although motor-gliders have small engines for extending their flight when necessary by sustaining the altitude with some being powerful enough to take off by self-launch.

The Schweizer SGS 1-23 is a United States Open and Standard Class, single-seat, mid-wing glider built by Schweizer Aircraft of Elmira, New York.

Lift is a meteorological phenomenon used as an energy source by soaring aircraft and soaring birds. The most common human application of lift is in sport and recreation. The three air sports that use soaring flight are: gliding, hang gliding and paragliding.

Gliding is a recreational activity and competitive air sport in which pilots fly unpowered aircraft known as gliders or sailplanes using naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmosphere to remain airborne. The word soaring is also used for the sport.

A glider or sailplane is a type of glider aircraft used in the leisure activity and sport of gliding. This unpowered aircraft can use naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmosphere to gain altitude. Sailplanes are aerodynamically streamlined and so can fly a significant distance forward for a small decrease in altitude.

In aviation, and particularly in the sport of gliding, a stick thermal is an illusion that the glider is climbing in a thermal when, in fact, the upward movement of the glider is caused by nothing more than the pilot pulling backwards on the control stick, causing the aircraft to climb, but lose airspeed.

The Akaflieg Braunschweig SB-11 is an experimental, single seat, variable geometry sailplane designed by aeronautical students in Germany. It won the 15 m span class at the World Gliding Championships of 1978 but its advances over the best, more conventional, opposition were not sufficient to lead to widespread imitation.

The drag curve or drag polar is the relationship between the drag on an aircraft and other variables, such as lift, the coefficient of lift, angle-of-attack or speed. It may be described by an equation or displayed as a graph. Drag may be expressed as actual drag or the coefficient of drag.

This is a glossary of acronyms, initialisms and terms used for gliding and soaring. This is a specialized subset of broader aviation, aerospace, and aeronautical terminology. Additional definitions can be found in the FAA Glider Flying Handbook.

Geoffrey Leonard Huson Stephenson was a radar engineer who developed weapon-locating radar and was the first person the cross the English Channel unaided in a glider.