Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the Court ruled that the Sixth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution requires U.S. states to provide attorneys to criminal defendants who are unable to afford their own. The case extended the right to counsel, which had been found under the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to impose requirements on the federal government, by imposing those requirements upon the states as well.

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that law enforcement in the United States must warn a person of their constitutional rights before interrogating them, or else the person's statements cannot be used as evidence at their trial. Specifically, the Court held that under the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the government cannot use a person's statements made in response to an interrogation while in police custody as evidence at the person's criminal trial unless they can show that the person was informed of the right to consult with a lawyer before and during questioning, and of the right against self-incrimination before police questioning, and that the defendant not only understood these rights but also voluntarily waived them before answering questions.

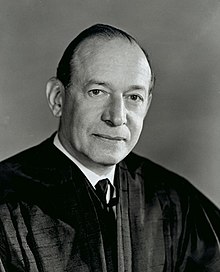

Abraham Fortas was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1965 to 1969. Born and raised in Memphis, Tennessee, Fortas graduated from Rhodes College and Yale Law School. He later became a law professor at Yale Law School and then an advisor for the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Fortas worked at the Department of the Interior under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and was appointed by President Harry S. Truman to delegations that helped set up the United Nations in 1945.

Epperson v. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97 (1968), was a unanimous landmark United States Supreme Court case that invalidated an Arkansas statute prohibiting the teaching of human evolution in the public schools. The Court held that the First Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits a state from requiring, in the words of the majority opinion, "that teaching and learning must be tailored to the principles or prohibitions of any religious sect or dogma." The Supreme Court declared the Arkansas statute unconstitutional because it violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. After this decision, some jurisdictions passed laws that required the teaching of creation science alongside evolution when evolution was taught. The Court also ruled these laws were unconstitutional in the 1987 case, Edwards v. Aguillard.

Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971), was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court holding that the First Amendment prevented the conviction of Paul Robert Cohen for the crime of disturbing the peace by wearing a jacket displaying "Fuck the Draft" in the public corridors of a California courthouse.

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970), is a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution requires an evidentiary hearing before a recipient of certain government welfare benefits can be deprived of such benefits.

Stanley v. Georgia, 394 U.S. 557 (1969), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States that helped to establish an implied "right to privacy" in U.S. law in the form of mere possession of obscene materials.

Brown v. Louisiana, 383 U.S. 131 (1966), was a United States Supreme Court case based on the First Amendment in the U.S. Constitution. It held that protesters have a First and Fourteenth Amendment right to engage in a peaceful sit-in at a public library. Justice Fortas wrote the plurality opinion and was joined by Justice Douglas and Justice Warren. Justices Brennan and Byron White concurred. Justices Black, Clark, Harlan and Stewart dissented.

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States that invalidated state durational residency requirements for public assistance and helped establish a fundamental "right to travel" in U.S. law. Shapiro was a part of a set of three welfare cases all heard during the 1968–69 term by the Supreme Court, alongside Harrell v. Tobriner and Smith v. Reynolds. Additionally, Shapiro, King v. Smith (1968), and Goldberg v. Kelly (1970) comprise the "Welfare Cases", a set of successful Supreme Court cases that dealt with welfare.

Garrity v. New Jersey, 385 U.S. 493 (1967), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that law enforcement officers and other public employees have the right to be free from compulsory self-incrimination. It gave birth to the Garrity warning, which is administered by investigators to suspects in internal and administrative investigations in a similar manner as the Miranda warning is administered to suspects in criminal investigations.

Adderley v. Florida, 385 U.S. 39 (1966), was a United States Supreme Court case regarding whether arrests for protesting in front of a jail were constitutional.

Schmerber v. California, 384 U.S. 757 (1966), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case in which the Court clarified the application of the Fourth Amendment's protection against warrantless searches and the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination for searches that intrude into the human body. Until Schmerber, the Supreme Court had not yet clarified whether state police officers must procure a search warrant before taking blood samples from criminal suspects. Likewise, the Court had not yet clarified whether blood evidence taken against the wishes of a criminal suspect may be used against that suspect in the course of a criminal prosecution.

Farmer v. Brennan, 511 U.S. 825 (1994), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that a prison official's "deliberate indifference" to a substantial risk of serious harm to an inmate violates the cruel and unusual punishment clause of the Eighth Amendment. Farmer built on two previous Supreme Court decisions addressing prison conditions, Estelle v. Gamble and Wilson v. Seiter. The decision marked the first time the Supreme Court directly addressed sexual assault in prisons.

United States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218 (1967), was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States that held that a criminal defendant has a Sixth Amendment right to counsel at a lineup held after indictment.

Time, Inc. v. Hill, 385 U.S. 374 (1967), is a United States Supreme Court case involving issues of privacy in balance with the First Amendment to the United States Constitution and principles of freedom of speech. The Court held 6–3 that the latter requires that merely negligent intrusions into the former by the media not be civilly actionable. It expanded that principle from its landmark defamation holding in New York Times v. Sullivan.

Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S. 589 (1967), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that states cannot prohibit employees from being members of the Communist Party and that this law was overbroad and too vague.

Hale v. Henkel, 201 U.S. 43 (1906), was a major United States Supreme Court case in which the Court established the power of a federal grand jury engaged in an investigation into corporate malfeasance to require the corporation in question to surrender its records.

Elrod v. Burns, 427 U.S. 347 (1976), is a United States Supreme Court decision regarding political speech of public employees. The Court ruled in this case that public employees may be active members in a political party, but cannot allow patronage to be a deciding factor in work related decisions. The court upheld the decision by the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals ruling in favor of the respondent.

Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, Council 31, No. 16-1466, 585 U.S. ___ (2018), abbreviated Janus v. AFSCME, is a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court on US labor law, concerning the power of labor unions to collect fees from non-union members. Under the Taft–Hartley Act of 1947, which applies to most of the private sector, union security agreements can be allowed by state law. The Supreme Court ruled that such union fees in the public sector violate the First Amendment right to free speech, overruling the 1977 decision in Abood v. Detroit Board of Education that had previously allowed such fees.

Edwards v. Vannoy, 593 U.S. ___ (2021), was a United States Supreme Court case involving the Court's prior decision in Ramos v. Louisiana, 590 U.S. ___ (2020), which had ruled that jury verdicts in criminal trials must be unanimous under the Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Supreme Court ruled 6–3 that Ramos did not apply retroactively to earlier cases prior to their verdict in Ramos.