Related Research Articles

Classical elements typically refer to water, earth, fire, air, and (later) aether, which were proposed to explain the nature and complexity of all matter in terms of simpler substances. Ancient cultures in Greece, Ancient Egypt, Persia, Babylonia, Japan, Tibet, and India had all similar lists, sometimes referring in local languages to "air" as "wind" and the fifth element as "void". The Chinese Wu Xing system lists Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water, though these are described more as energies or transitions rather than as types of material.

Air is one of the four classical elements along with water, earth and fire in ancient Greek philosophy and in Western alchemy.

Water is one of the classical elements in ancient Greek philosophy, in the Asian Indian system Panchamahabhuta, and in the Chinese cosmological and physiological system Wu Xing. In contemporary esoteric traditions, it is commonly associated with the qualities of emotion and intuition.

Earth is one of the classical elements, in some systems being one of the four along with air, fire, and water.

The flat Earth model is an archaic conception of Earth's shape as a plane or disk. Many ancient cultures subscribed to a flat Earth cosmography, including Greece until the classical period, the Bronze Age and Iron Age civilizations of the Near East until the Hellenistic period, India until the Gupta period, and China until the 17th century.

The cosmos is the Universe. Using the word cosmos rather than the word universe implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity; the opposite of chaos. The cosmos, and our understanding of the reasons for its existence and significance, are studied in cosmology – a very broad discipline covering any scientific, religious, or philosophical contemplation of the cosmos and its nature, or reasons for existing. Religious and philosophical approaches may include in their concepts of the cosmos various spiritual entities or other matters deemed to exist outside our physical universe.

In astronomy and navigation, the celestial sphere is an abstract sphere that has an arbitrarily large radius and is concentric to Earth. All objects in the sky can be conceived as being projected upon the inner surface of the celestial sphere, which may be centered on Earth or the observer. If centered on the observer, half of the sphere would resemble a hemispherical screen over the observing location.

Aristarchus of Samos was an ancient Greek astronomer and mathematician who presented the first known heliocentric model that placed the Sun at the center of the known universe, with the Earth revolving around the Sun once a year and rotating about its axis once a day. He was influenced by Philolaus of Croton, but Aristarchus identified the "central fire" with the Sun, and he put the other planets in their correct order of distance around the Sun. Like Anaxagoras before him, he suspected that the stars were just other bodies like the Sun, albeit farther away from Earth. His astronomical ideas were often rejected in favor of the geocentric theories of Aristotle and Ptolemy. Nicolaus Copernicus attributed the heliocentric theory to Aristarchus. Aristarchus also estimated the sizes of the Sun and Moon as compared to Earth's size, and the distances to the Sun and Moon.

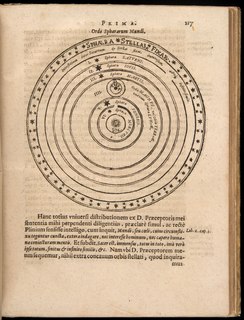

In astronomy, the geocentric model is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under the geocentric model, the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets all orbited Earth. The geocentric model was the predominant description of the cosmos in many ancient civilizations, such as those of Aristotle in Classical Greece and Ptolemy in Roman Egypt.

The earliest documented mention of the spherical Earth concept dates from around the 5th century BC, when it was mentioned by ancient Greek philosophers. In the 3rd century BC, Hellenistic astronomy established the roughly spherical shape of the Earth as a physical fact and calculated the Earth's circumference. This knowledge was gradually adopted throughout the Old World during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. A practical demonstration of Earth's sphericity was achieved by Ferdinand Magellan and Juan Sebastián Elcano's circumnavigation (1519–1522).

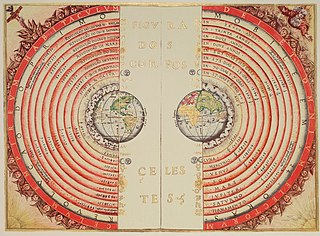

The celestial spheres, or celestial orbs, were the fundamental entities of the cosmological models developed by Plato, Eudoxus, Aristotle, Ptolemy, Copernicus, and others. In these celestial models, the apparent motions of the fixed stars and planets are accounted for by treating them as embedded in rotating spheres made of an aetherial, transparent fifth element (quintessence), like jewels set in orbs. Since it was believed that the fixed stars did not change their positions relative to one another, it was argued that they must be on the surface of a single starry sphere.

The fixed stars compose the background of astronomical objects that appear to not move relative to each other in the night sky compared to the foreground of Solar System objects that do. Generally, the fixed stars are taken to include all stars other than the Sun. Nebulae and other deep-sky objects may also be counted among the fixed stars.

Meteorology is a treatise by Aristotle. The text discusses what Aristotle believed to have been all the affections common to air and water, and the kinds and parts of the earth and the affections of its parts. It includes early accounts of water evaporation, earthquakes, and other weather phenomena.

In Aristotelian physics and Greek astronomy, the sublunary sphere is the region of the geocentric cosmos below the Moon, consisting of the four classical elements: earth, water, air, and fire.

Greek astronomy is astronomy written in the Greek language in classical antiquity. Greek astronomy is understood to include the ancient Greek, Hellenistic, Greco-Roman, and Late Antiquity eras. It is not limited geographically to Greece or to ethnic Greeks, as the Greek language had become the language of scholarship throughout the Hellenistic world following the conquests of Alexander. This phase of Greek astronomy is also known as Hellenistic astronomy, while the pre-Hellenistic phase is known as Classical Greek astronomy. During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, much of the Greek and non-Greek astronomers working in the Greek tradition studied at the Musaeum and the Library of Alexandria in Ptolemaic Egypt.

Celestial Matters is a science fantasy novel by American writer Richard Garfinkle, set in an alternate universe with different laws of physics. Published by Tor Books in 1996, it is a work of alternate history and elaborated "alternate science", as the physics of this world and its surrounding cosmos are based on the physics of Aristotle and ancient Chinese Taoist alchemy.

Aristotelian physics is the form of natural science described in the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle. In his work Physics, Aristotle intended to establish general principles of change that govern all natural bodies, both living and inanimate, celestial and terrestrial – including all motion, quantitative change, qualitative change, and substantial change. To Aristotle, 'physics' was a broad field that included subjects that would now be called the philosophy of mind, sensory experience, memory, anatomy and biology. It constitutes the foundation of the thought underlying many of his works.

Ancient, medieval and Renaissance astronomers and philosophers developed many different theories about the dynamics of the celestial spheres. They explained the motions of the various nested spheres in terms of the materials of which they were made, external movers such as celestial intelligences, and internal movers such as motive souls or impressed forces. Most of these models were qualitative, although a few of them incorporated quantitative analyses that related speed, motive force and resistance.

An astronomical system positing that the Earth, Moon, Sun and planets revolve around an unseen "Central Fire" was developed in the 5th century BC and has been attributed to the Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus. The system has been called "the first coherent system in which celestial bodies move in circles", anticipating Copernicus in moving "the earth from the center of the cosmos [and] making it a planet". Although its concepts of a Central Fire distinct from the Sun, and a nonexistent "Counter-Earth" were erroneous, the system contained the insight that "the apparent motion of the heavenly bodies" was due to "the real motion of the observer". How much of the system was intended to explain observed phenomena and how much was based on myth and religion is disputed. While the departure from traditional reasoning is impressive, other than the inclusion of the 5 visible planets, very little of the Pythagorean system is based on genuine observation. In retrospect, Philolaus's views are "less like scientific astronomy than like symbolical speculation."

The historical models of the Solar System began during prehistoric periods and is updated to this day. The models of the Solar System throughout history were first represented in the early form of cave markings and drawings, calendars and astronomical symbols. Then books and written records then became the main source of information that expressed the way the people of the time thought of the Solar System.

References

- ↑ Stephen Toulmin, Night Sky at Rhodes (1963) p. 37

- ↑ Helge Kragh, Conceptions of Cosmos (2007) p. 31

- ↑ J. B. Bury, The Cambridge Medieval History Vol VIII (1936) p. 669

- ↑ I. Rivers, Classical and Christian Ideas in English Renaissance Poetry (1994) p. 69 and p. 79

- ↑ Dante, Paradiso (Penguin 1975) p. 61

- ↑ G. Bull transl., the Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini (Penguin 1956) p. 345

- ↑ B. Stephenson, The Music of the Heavens (2014) p. 60

- ↑ Stephen Toulmin, Night Sky at Rhodes (1963) p. 100

- ↑ M. Ashley, England in the Seventeenth Century (1960) p. 35

- ↑ Helge Kragh, Conceptions of Cosmos (2007) p. 61