Related Research Articles

The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, was a secret revolutionary society founded in the Ottoman territories in Europe, that operated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Hristo Tatarchev was a Macedonian Bulgarian doctor, revolutionary and one of the founders of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO). Tatarchev authored several political journalistic works between the First and Second World War.

Nikola Yanakiev Karev was a Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary. He was born in Kruševo and died in the village of Rajčani both today in North Macedonia. Karev was a local leader of what later became known as the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO). He was also a teacher in the Bulgarian Exarchate school system in his native area, and a member of the Bulgarian Workers' Social Democratic Party. Today he is considered a hero in Bulgaria and in North Macedonia.

The Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia was the supreme legislative and executive people's representative body of the communist Macedonian state from August 1944 until the end of World War II. The body was set up by the Macedonian Partisans during the final stages of the World War II in Yugoslav Macedonia. That occurred clandestinely in August 1944, in the Bulgarian occupation zone of Yugoslavia. Simultaneously another state was declared by pro-Nazi Germany Macedonian right-wing nationalists.

Panko Brashnarov was a revolutionary and member of the left wing of the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO) and IMRO (United) later. As with many other IMARO members of the time, historians from North Macedonia consider him an ethnic Macedonian, whereas historians in Bulgaria consider him a Bulgarian. The name of Brashnarov was a taboo in Yugoslav Macedonia, but he was rehabilitated during the 1990s, after the country gained its independence.

Dimitar Vlahov was a politician from the region of Macedonia and member of the left wing of the Macedonian-Adrianople revolutionary movement. As with many other IMRO members of the time, historians from North Macedonia consider him an ethnic Macedonian and in Bulgaria he is considered a Bulgarian. According to Dimitar Bechev, Vlahov declared himself until the early 1930s as a Bulgarian and afterwards as an ethnic Macedonian.

Mihailo Apostolski was a Macedonian general, partisan, military theoretician, politician, academic and historian. He was the commander of the General Staff of the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Macedonia, colonel general of the Yugoslav People's Army, and was declared a People's Hero of Yugoslavia.

The Independent State of Macedonia was a proposed puppet state of Nazi Germany during the Second World War in the territory of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia that had been occupied by the Kingdom of Bulgaria following the invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941.

The Macedonian Youth Secret Revolutionary Organization or MMTRO was a secret pro-Bulgarian youth organization established by the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, active in Macedonia between 1922 and 1941. The statue of MMTRO was approved personally by the leader of the IMRO, Todor Alexandrov. The aim of MMTRO was in concordance with the statue of IMRO – unification of all of Macedonia in an autonomous unit within Greater Bulgaria.

The resolution of the Comintern of January 11, 1934, was an official political document, in which for the first time, an authoritative international organization has recognized the existence of a separate Macedonian nation and Macedonian language.

Dimitar Gyuzelov was a Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary and philosopher. He is the father of Macedonian writer Bogomil Gyuzel and artist Liljana Gyuzelova, who between 1996 and 2006 worked on an art installation titled The Perpetual Return, dedicated to her father, his murder, and the stigma that the children of prominent Bulgarians who had been persecuted by the Yugoslav authorities after 1945 had to endure.

Trenko Rujanović, known as Vojvoda Trenko, was a Macedonian Serb Chetnik and Bulgarian apostate.

Nikola Kirov was a Bulgarian teacher, revolutionary and public figure, a member of IMRO.

Day of the Macedonian Uprising is a public holiday in North Macedonia, commemorating what is considered there as the beginning of the communist resistance against fascism during World War II in Yugoslav Macedonia, on October 11.

"Gotse Delchev" Brigade was a military unit composed of conscripts and volunteers from the region of Macedonia. The brigade was named after the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization revolutionary Gotse Delchev.

Dimitar Chkatrov was Bulgarian activist in Vardar Macedonia. He was born in Prilep, then in the Ottoman Empire in 1900. Chkatrov began to study at the Bulgarian primary school in his hometown, but after the establishment of Serbian rule following the First World War, he completed his education in a Serbian school. In the first half of the 1920s, Chkatrov studied civil engineering at the University of Belgrade. He took an active part in the resistance against the policy of Serbianization in Yugoslav Macedonia. In 1927, a trial was organized in Skopje against a group of Bulgarian students. They were arrested after a failure in the Macedonian Youth Secret Revolutionary Organization. Dimitar Chkatrov was sentenced to 10 years in prison. In an unsuccessful attempt to escape, he was shot in the chest, and was returned to prison to serve his sentence. Chkatrov participated in the establishment of the Bulgarian Action Committees in Prilep in 1941. After the accession of most of Vardar Macedonia to Bulgaria in the same year he was closely involved in the establishment of civic Bulgarian national clubs. In 1945 Dimitar Chkatrov was arrested by the new Yugoslav communist authorities and accused of being pro-Bulgarian fascist collaborator. He was sentenced to death by firing squad. Chkatrov was shot in 1945 near Skopje, together with his friend Dimitar Gyuzelov.

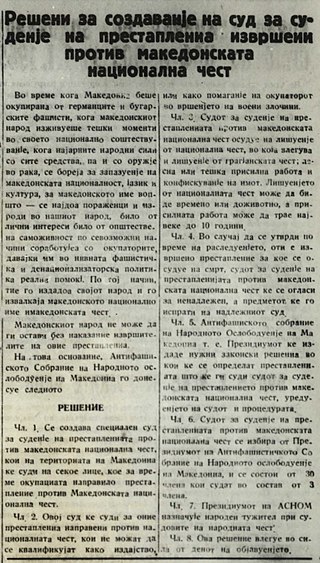

The Law for the Protection of Macedonian National Honour was a statute passed by the government of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia at the end of 1944. The Presidium of Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM) established a special court for the implementation of this law, which came into effect on 3 January 1945. This decision was taken at the second session of this assembly on 28–31 December 1944.

Vasil Atanasov Ivanovski also known by his pseudonym Bistrishki, was a Bulgarian communist activist, publicist, theoretician of the Macedonian nation within the IMRO (United). According to the historiography in North Macedonia, Ivanovski is its founder and a prominent "fighter for the affirmation of the Macedonian national identity", and according to the Bulgarian historiography, he is known "for his wanderings on the Macedonian question". Per the Macedonian historian Ivan Katardžiev, such activists of the IMRO (United) and the Bulgarian Communist Party never managed to break with their pro-Bulgarian aspirations.

Alekso Martulkov, born as Aleksandar Onchev Martulkov, was a publicist and one of the first socialist revolutionaries from the region of Macedonia. He was a member of the Bulgarian Workers' Social Democratic Party and later the People's Federative Party and the Bulgarian Communist Party. Simultaneously, he was a member of the IMRO and subsequently the IMRO (United). He advocated for the independence of Macedonia. Martulkov was also a member of the Bulgarian Parliament, as well as the Presidium of ASNOM and the parliament of SR Macedonia. He is considered a Macedonian in the Macedonian historiography and a Bulgarian in the Bulgarian historiography.

Božidar "Božo" Vidoeski was a Macedonian linguist and the founder of Macedonian dialectology.

References

- ↑ Ivan Katardžiev, Macedonia and its neighbours: past, present, future, Menora, 2001, p. 178.

- ↑ Hristo Adonov-Poljanski, Documents on the Struggle of the Macedonian People for Independence and a Nation-state: From the end of World War One to the creation of a nation-state, Volume 2, Univerzitet "Kiril i Metodij", Skopje. Kultura, 1985, p. 476.

- ↑ Николов, Борис Й. Вътрешна македоно-одринска революционна организация. Войводи и ръководители (1893-1934). Биографично-библиографски справочник, София, 2001, стр. 78.

- ↑ Минчев, Димитър. Българските акционни комитети в Македония - 1941 г. София, Македонски научен институт, 1995. с. 26.

- ↑ Николов, Борис. ВМОРО – псевдоними и шифри 1893-1934, Звезди, 1999, стр.88.

- ↑ Църнушанов, Коста. Македонизмът и съпротивата на Македония срещу него. Университетско издателство „Св. Климент Охридски“, София, 1992, стр. 152.

- ↑ Михайлов, Иван. Спомени, том III, Луврен, 1967, стр. 363-376, в: Билярски, Цочо. Подвигът на Мара Бунева (съкратено издание), Анико, София, 2010, стр.28.

- ↑ Zielonka, Jan; Pravda, Alex (2001). Democratic consolidation in Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-19-924409-6.

Unlike the Slovene and Croatian identities, which existed independently for a long period before the emergence of SFRY, Macedonian identity and language were themselves a product federal Yugoslavia, and took shape only after 1944. Again unlike Slovenia and Croatia, the very existence of a separate Macedonian identity was questioned—albeit to a different degree—by both the governments and the public of all the neighboring nations (Greece being the most intransigent)

- ↑ Kaufman, Stuart J. (2001). Modern hatreds: the symbolic politics of ethnic war. New York: Cornell University Press. p. 193. ISBN 0-8014-8736-6.

The key fact about Macedonian nationalism is that it is new: in the early twentieth century, Macedonian villagers defined their identity religiously—they were either "Bulgarian," "Serbian," or "Greek" depending on the affiliation of the village priest. While Bulgarian was most common affiliation then, mistreatment by occupying Bulgarian troops during WWII cured most Macedonians from their pro-Bulgarian sympathies, leaving them embracing the new Macedonian identity promoted by the Tito regime after the war.

- ↑ "At the end of the WWI there were very few historians or ethnographers, who claimed that a separate Macedonian nation existed.... Of those Slavs who had developed some sense of national identity, the majority probably considered themselves to be Bulgarians, although they were aware of differences between themselves and the inhabitants of Bulgaria.... The question as of whether a Macedonian nation actually existed in the 1940s when a Communist Yugoslavia decided to recognize one is difficult to answer. Some observers argue that even at this time it was doubtful whether the Slavs from Macedonia considered themselves to be a nationality separate from the Bulgarians.The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world, Loring M. Danforth, Princeton University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-691-04356-6, pp. 65-66.

- ↑ "Most of the Slavophone inhabitants in all parts of divided Macedonia, perhaps a million and a half in all – had a Bulgarian national consciousness at the beginning of the Occupation; and most Bulgarians, whether they supported the Communists, VMRO, or the collaborating government, assumed that all Macedonia would fall to Bulgaria after the WWII. Tito was determined that this should not happen. The first Congress of AVNOJ in November 1942 had paranteed equal rights to all the 'peoples of Yugoslavia', and specified the Macedonians among them...The Communist Party of Macedonia, which had passed through a troubled time, first under a pro-Bulgarian leadership and then under pro-Yugoslav Macedonians, was taken in hand early in 1943 by Tempo, who formed a new Central Committee and informed it that it was now an integral part of the Yugoslav CP. "The struggle for Greece, 1941-1949, Christopher Montague Woodhouse, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2002, ISBN 1-85065-492-1, p. 67.

- ↑ "Despite the slight change of the younger generation in the 1930s, reflected in the slogan "Macedonia for the Macedonians", anti-Serbian and pro-Bulgarian sentiment still prevailed. Even "Macedonia for the Macedonians" signalled in many ways an acceptance of the state of Yugoslavia and an attempt to gain autonomy within it. The collapse of Yugoslavia changed all this. There is a little doubt that the initial reaction among large sections of the population of Vardar Macedonia who had suffered so much under the Serbian repression was to greet the Bulgarians as liberators." Who are the Macedonians? Hugh Poulton, Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1995, ISBN 978-1-85065-238-0, p. 101.

- ↑ Todor Chepreganov et al., History of the Macedonian People, Institute of National History, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University, Skopje,(2008) p. 254.

- ↑ Macedonia and the Macedonians: A History, Andrew Rossos, Hoover Press, 2008, ISBN 9780817948832, p. 189.

- ↑ Stephen E. Palmer, Robert R. King, Yugoslav communism and the Macedonian question, Archon Books, 1971, ISBN 0208008217, Chapter 9: The encouragement of Macedonian culture.In 1945

- ↑ Michael Palairet, Macedonia: A Voyage through History, Volume 2, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016, ISBN 1443888494, p. 293.

- ↑ Гоцев, Димитър. Новата национално-освободителна борба във Вардарска Македония 1944-1991 г., Македонски научен институт, София, 1998, глава Първите политически процеси.