Æthelred was king of Mercia from 675 until 704. He was the son of Penda of Mercia and came to the throne in 675, when his brother, Wulfhere of Mercia, died from an illness. Within a year of his accession he invaded Kent, where his armies destroyed the city of Rochester. In 679 he defeated his brother-in-law, Ecgfrith of Northumbria, at the Battle of the Trent: the battle was a major setback for the Northumbrians, and effectively ended their military involvement in English affairs south of the Humber. It also permanently returned the kingdom of Lindsey to Mercia's possession. However, Æthelred was unable to re-establish his predecessors' domination of southern Britain.

Scandinavian York or Viking York is a term used by historians for what is now Yorkshire during the period of Scandinavian domination from late 9th century until it was annexed and integrated into England after the Norman Conquest; in particular, it is used to refer to York, the city controlled by these kings and earls. The Kingdom of Jórvíc was closely associated with the much longer-lived Kingdom of Dublin throughout this period.

Hexham Abbey is a Grade I listed church dedicated to St Andrew, in the town of Hexham, Northumberland, in the North East of England. Originally built in AD 674, the Abbey was built up during the 12th century into its current form, with additions around the turn of the 20th century. Since the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1537, the Abbey has been the parish church of Hexham. In 2014 the Abbey regained ownership of its former monastic buildings, which had been used as Hexham magistrates' court, and subsequently developed them into a permanent exhibition and visitor centre, telling the story of the Abbey's history.

Eanred was king of Northumbria in the early ninth century.

Eanbald II was an eighth century Archbishop of York and correspondent of Alcuin.

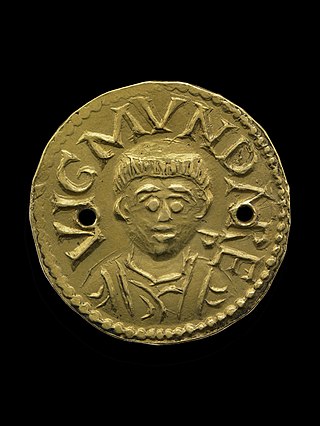

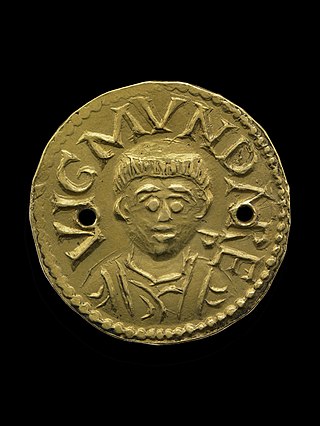

Wigmund was a medieval Archbishop of York, who was consecrated in 837 and died in 854.

Wulfhere was Archbishop of York between 854 and 900.

Eardwulf was king of Northumbria from 796 to 806, when he was deposed and went into exile. He may have had a second reign from 808 until perhaps 811 or 830. Northumbria in the last years of the eighth century was the scene of dynastic strife between several noble families: in 790, king Æthelred I attempted to have Eardwulf assassinated. Eardwulf's survival may have been viewed as a sign of divine favour. A group of nobles conspired to assassinate Æthelred in April 796 and he was succeeded by Osbald: Osbald's reign lasted only twenty-seven days before he was deposed and Eardwulf became king on 14 May 796.

Æthelred was king of Northumbria in the middle of the ninth century, but his dates are uncertain. N. J. Higham gives 840 to 848, when he was killed, with an interruption in 844 when Rædwulf usurped the throne, but was killed the same year fighting against the Vikings. Barbara Yorke agrees, and adds that Æthelred was the son of his predecessor, Eanred, but dates his death 848 or 849. D. P. Kirby thinks that an accession date of 844 is more likely, but notes that a coin of Eanred dated stylistically no earlier than 850 may require a more radical revision of dates. David Rollason accepts the coin evidence, and dates Æthelred's reign from c.854 to c. 862, with Rædwulf's usurpation in 858.

Rædwulf was king of Northumbria for a short time. His ancestry is not known, but it is possible that he was a kinsman of Osberht and Ælla.

The history of the English penny can be traced back to the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of the 7th century: to the small, thick silver coins known to contemporaries as pæningas or denarii, though now often referred to as sceattas by numismatists. Broader, thinner pennies inscribed with the name of the king were introduced to Southern England in the middle of the 8th century. Coins of this format remained the foundation of the English currency until the 14th century.

The Yorkshire Museum is a museum in York, England. It was opened in 1830, and has five permanent collections, covering biology, geology, archaeology, numismatics and astronomy.

Events from the 10th century in the Kingdom of England.

Events from the 9th century in England.

Events from the 7th century in England.

The styca was a small coin minted in pre-Viking Northumbria, originally in base silver and subsequently in a copper alloy. Production began in the 790s and continued until the 850s, though the coin remained in circulation until the Viking conquest of Northumbria in 867.

Elizabeth Jean Elphinstone Pirie was a British numismatist specialising in ninth-century Northumbrian coinage, and museum curator, latterly as Keeper of Archaeology at Leeds City Museum from 1960 to 1991. She wrote eight books and dozens of articles throughout her career. She was a fellow of the Royal Numismatic Society, president of the Yorkshire Numismatic Society and a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London.

St Leonard's Place is a street in the city centre of York, in England.

The Hexham hoard is a 9th-century hoard of eight thousand copper-alloy coins of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria, which were discovered whilst a grave was being dug close to Hexham Abbey in 1832.

The Kirkoswald Hoard is a ninth-century hoard of 542 copper alloy coins of the Kingdom of Northumbria and a silver trefoil ornament, which were discovered amongst tree roots in 1808 within the parish of Kirkoswald in Cumbria, UK.