Related Research Articles

In English church history,Nonconformists were Protestant Christians who did not "conform" to the governance and usages of the state church,the Church of England.

Scottish literature is literature written in Scotland or by Scottish writers. It includes works in English,Scottish Gaelic,Scots,Brythonic,French,Latin,Norn or other languages written within the modern boundaries of Scotland.

Scotland in the Middle Ages concerns the history of Scotland from the departure of the Romans to the adoption of major aspects of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century.

David William Bebbington is a British historian who is a professor of history at the University of Stirling in Scotland and a distinguished visiting professor of history at Baylor University. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and the Royal Historical Society.

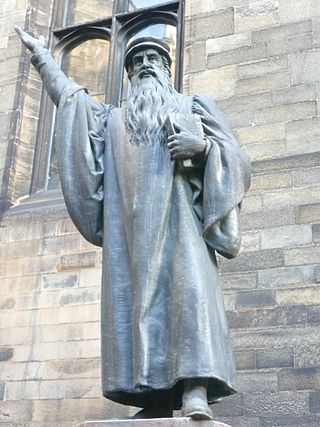

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Scotland broke with the Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Kirk (church),which was strongly Presbyterian in its outlook. It was part of the wider European Protestant Reformation that took place from the sixteenth century.

A conventicle originally signified no more than an assembly and was frequently used by ancient writers for a church. At a semantic level conventicle is only a good Latinized synonym of the Greek word for church,and points to Jesus' promise in Matthew 18:20,"Where two or three are met together in my name."

Theatre in Scotland refers to the history of the performing arts in Scotland,or those written,acted and produced by Scots. Scottish theatre generally falls into the Western theatre tradition,although many performances and plays have investigated other cultural areas. The main influences are from North America,England,Ireland and from Continental Europe. Scotland's theatrical arts were generally linked to the broader traditions of Scottish and English-language literature and to British and Irish theatre,American literature and theatrical artists. As a result of mass migration,both to and from Scotland,in the modern period,Scottish literature has been introduced to a global audience,and has also created an increasingly multicultural Scottish theatre.

The Toleration Act 1688,also referred to as the Act of Toleration,was an Act of the Parliament of England. Passed in the aftermath of the Glorious Revolution,it received royal assent on 24 May 1689.

The Renaissance in Scotland was a cultural,intellectual and artistic movement in Scotland,from the late fifteenth century to the beginning of the seventeenth century. It is associated with the pan-European Renaissance that is usually regarded as beginning in Italy in the late fourteenth century and reaching northern Europe as a Northern Renaissance in the fifteenth century. It involved an attempt to revive the principles of the classical era,including humanism,a spirit of scholarly enquiry,scepticism,and concepts of balance and proportion. Since the twentieth century,the uniqueness and unity of the Renaissance has been challenged by historians,but significant changes in Scotland can be seen to have taken place in education,intellectual life,literature,art,architecture,music,science and politics.

Romanticism in Scotland was an artistic,literary and intellectual movement that developed between the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth centuries. It was part of the wider European Romantic movement,which was partly a reaction against the Age of Enlightenment,emphasising individual,national and emotional responses,moving beyond Renaissance and Classicist models,particularly into nostalgia for the Middle Ages. The concept of a separate national Scottish Romanticism was first articulated by the critics Ian Duncan and Murray Pittock in the Scottish Romanticism in World Literatures Conference held at UC Berkeley in 2006 and in the latter's Scottish and Irish Romanticism (2008),which argued for a national Romanticism based on the concepts of a distinct national public sphere and differentiated inflection of literary genres;the use of Scots language;the creation of a heroic national history through an Ossianic or Scottian 'taxonomy of glory' and the performance of a distinct national self in diaspora.

Scottish religion in the eighteenth century includes all forms of religious organisation and belief in Scotland in the eighteenth century. This period saw the beginnings of a fragmentation of the Church of Scotland that had been created in the Reformation and established on a fully Presbyterian basis after the Glorious Revolution. These fractures were prompted by issues of government and patronage,but reflected a wider division between the Evangelicals and the Moderate Party. The legal right of lay patrons to present clergymen of their choice to local ecclesiastical livings led to minor schisms from the church. The first in 1733,known as the First Secession and headed by figures including Ebenezer Erskine,led to the creation of a series of secessionist churches. The second in 1761 led to the foundation of the independent Relief Church.

Scottish religion in the nineteenth century includes all forms of religious organisation and belief in Scotland in the 19th century. This period saw a reaction to the population growth and urbanisation of the Industrial Revolution that had undermined traditional parochial structures and religious loyalties. The established Church of Scotland reacted with a programme of church building from the 1820s. Beginning in 1834 the "Ten Years' Conflict" ended in a schism from the established Church of Scotland led by Dr Thomas Chalmers known as the Great Disruption of 1843. Roughly a third of the clergy,mainly from the North and Highlands,formed the separate Free Church of Scotland. The evangelical Free Church and other secessionist churches grew rapidly in the Highlands and Islands and urban centres. There were further schisms and divisions,particularly between those who attempted to maintain the principles of Calvinism and those that took a more personal and flexible view of salvation. However,there were also mergers that cumulated in the creation of a United Free Church in 1900 that incorporated most of the secessionist churches.

Music in Medieval Scotland includes all forms of musical production in what is now Scotland between the fifth century and the adoption of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century. The sources for Scottish Medieval music are extremely limited. There are no major musical manuscripts for Scotland from before the twelfth century. There are occasional indications that there was a flourishing musical culture. Instruments included the cithara,tympanum,and chorus. Visual representations and written sources demonstrate the existence of harps in the Early Middle Ages and bagpipes and pipe organs in the Late Middle Ages. As in Ireland,there were probably filidh in Scotland,who acted as poets,musicians and historians. After this "de-gallicisation" of the Scottish court in the twelfth century,a less highly regarded order of bards took over the functions of the filidh and they would continue to act in a similar role in the Scottish Highlands and Islands into the eighteenth century.

Church music in Scotland includes all musical composition and performance of music in the context of Christian worship in Scotland,from the beginnings of Christianisation in the fifth century,to the present day. The sources for Scottish Medieval music are extremely limited due to factors including a turbulent political history,the destructive practices of the Scottish Reformation,the climate and the relatively late arrival of music printing. In the early Middle Ages,ecclesiastical music was dominated by monophonic plainchant,which led to the development of a distinct form of liturgical Celtic chant. It was superseded from the eleventh century by more complex Gregorian chant. In the High Middle Ages,the need for large numbers of singing priests to fulfill the obligations of church services led to the foundation of a system of song schools,to train boys as choristers and priests. From the thirteenth century,Scottish church music was increasingly influenced by continental developments. Monophony was replaced from the fourteenth century by the Ars Nova consisting of complex polyphony. Survivals of works from the first half of the sixteenth century indicate the quality and scope of music that was undertaken at the end of the Medieval period. The outstanding Scottish composer of the first half of the sixteenth century was Robert Carver,who produced complex polyphonic music.

The history of popular religion in Scotland includes all forms of the formal theology and structures of institutional religion,between the earliest times of human occupation of what is now Scotland and the present day. Very little is known about religion in Scotland before the arrival of Christianity. It is generally presumed to have resembled Celtic polytheism and there is evidence of the worship of spirits and wells. The Christianisation of Scotland was carried out by Irish-Scots missionaries and to a lesser extent those from Rome and England,from the sixth century. Elements of paganism survived into the Christian era. The earliest evidence of religious practice is heavily biased toward monastic life. Priests carried out baptisms,masses and burials,prayed for the dead and offered sermons. The church dictated moral and legal matters and impinged on other elements of everyday life through its rules on fasting,diet,the slaughter of animals and rules on purity and ritual cleansing. One of the main features of Medieval Scotland was the Cult of Saints,with shrines devoted to local and national figures,including St Andrew,and the establishment of pilgrimage routes. Scots also played a major role in the Crusades. Historians have discerned a decline of monastic life in the late medieval period. In contrast,the burghs saw the flourishing of mendicant orders of friars in the later fifteenth century. As the doctrine of Purgatory gained importance the number of chapelries,priests and masses for the dead within parish churches grew rapidly. New "international" cults of devotion connected with Jesus and the Virgin Mary began to reach Scotland in the fifteenth century. Heresy,in the form of Lollardry,began to reach Scotland from England and Bohemia in the early fifteenth century,but did not achieve a significant following.

The evangelical revival in Scotland was a series of religious movements in Scotland from the eighteenth century,with periodic revivals into the twentieth century. It began in the later 1730s as congregations experienced intense "awakenings" of enthusiasm,renewed commitment and rapid expansion. This was first seen at Easter Ross in the Highlands in 1739 and most famously in the Cambuslang Wark near Glasgow in 1742. Most of the new converts were relatively young and from the lower groups in society. Unlike awakenings elsewhere,the early revival in Scotland did not give rise to a major religious movement,but mainly benefited the secession churches,who had broken away from the Church of Scotland. In the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century the revival entered a second wave,known in the US as the Second Great Awakening. In Scotland this was reflected in events like the Kilsyth Revival in 1839. The early revival mainly spread in the Central Belt,but it became active in the Highlands and Islands,peaking towards the middle of the nineteenth century. Scotland gained many of the organisations associated with the revival in England,including Sunday Schools,mission schools,ragged schools,Bible societies and improvement classes.

The history of Christianity in Britain covers the religious organisations,policies,theology and popular religiosity since ancient times.

The Liberation Society was an organisation in Victorian England that campaigned for disestablishment of the Church of England. It was founded in 1844 by Edward Miall as the British Anti-State Church Association and was renamed in 1853 as the Society for the Liberation of Religion from State Patronage and Control,from which the shortened common name of Liberation Society derived.

Scottish Protestant missions are organised programmes of outreach and conversion undertaken by Protestant denominations within Scotland,or by Scottish people. Long after the triumph of the Church of Scotland in the Lowlands,Highlanders and Islanders clung to a form of Christianity infused with animistic folk beliefs and practices. From 1708 the Scottish Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SSPCK) began working in the area. In 1797 James Haldane founded the non-denominational Society for the Propagation of the Gospel at Home. Dozens of lay preachers,divinity students and English preachers were sent to the region. In the early nineteenth century a variety of organisations were formed to support evangelism to the region.

The British Weekly:A Journal of Social and Christian Progress was a significant publication from its founding in 1886 well into the 20th century. One of the most successful religious newspapers of its time,it was published by Hodder &Stoughton. It was "a central force in shaping and promoting the 'Nonconformist conscience'",according to the Dictionary of Nineteenth-century Journalism in Great Britain and Ireland.

References

- ↑ "W T Stead: Nonconformist and Newspaper Prophet". The University of Edinburgh. 25 September 2019.

- ↑ Talbot, Brian (April 2021). "Stewart J. Brown, W. T. Stead: Nonconformist and Newspaper Prophet". Scottish Church History. pp. 70–73. doi:10.3366/sch.2021.0048.