Alfred Habdank Skarbek Korzybski was a Polish-American independent scholar who developed a field called general semantics, which he viewed as both distinct from, and more encompassing than, the field of semantics. He argued that human knowledge of the world is limited both by the human nervous system and the languages humans have developed, and thus no one can have direct access to reality, given that the most we can know is that which is filtered through the brain's responses to reality. His best known dictum is "The map is not the territory".

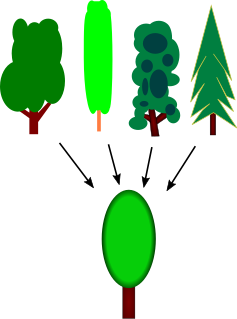

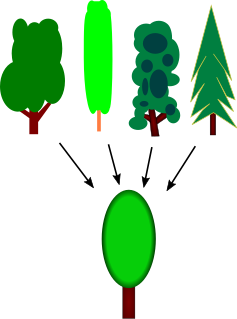

Abstraction in its main sense is a conceptual process wherein general rules and concepts are derived from the usage and classification of specific examples, literal signifiers, first principles, or other methods.

Concepts are defined as abstract ideas. They are understood to be the fundamental building blocks of the concept behind principles, thoughts and beliefs. They play an important role in all aspects of cognition. As such, concepts are studied by several disciplines, such as linguistics, psychology, and philosophy, and these disciplines are interested in the logical and psychological structure of concepts, and how they are put together to form thoughts and sentences. The study of concepts has served as an important flagship of an emerging interdisciplinary approach called cognitive science.

E-Prime is a restricted form of English in which all forms of the verb to be are to be excluded by authors.

The hypothesis of linguistic relativity, also known as the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, the Whorf hypothesis, or Whorfianism, is a principle suggesting that the structure of a language affects its speakers' worldview or cognition, and thus people's perceptions are relative to their spoken language.

Sanity refers to the soundness, rationality, and health of the human mind, as opposed to insanity. A person is sane if they are rational. In modern society, the term has become exclusively synonymous with compos mentis, in contrast with non compos mentis, or insanity, meaning troubled conscience. A sane mind is nowadays considered healthy both from its analytical - once called rational - and emotional aspects. According to the writer G. K. Chesterton, sanity involves wholeness, whereas insanity implies narrowness and brokenness.

Semantics is the study of reference, meaning, or truth. The term can be used to refer to subfields of several distinct disciplines, including philosophy, linguistics and computer science.

In computer science, denotational semantics is an approach of formalizing the meanings of programming languages by constructing mathematical objects that describe the meanings of expressions from the languages. Other approaches providing formal semantics of programming languages include axiomatic semantics and operational semantics.

In computer science, abstract interpretation is a theory of sound approximation of the semantics of computer programs, based on monotonic functions over ordered sets, especially lattices. It can be viewed as a partial execution of a computer program which gains information about its semantics without performing all the calculations.

In software engineering and computer science, abstraction is:

General semantics is concerned with how events translate to perceptions, how they are further modified by the names and labels we apply to them, and how we might gain a measure of control over our own responses, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral. Proponents characterize general semantics as an antidote to certain kinds of delusional thought patterns in which incomplete and possibly warped mental constructs are projected onto the world and treated as reality itself. After partial launches under the names human engineering and humanology, Polish-American originator Alfred Korzybski (1879–1950) fully launched the program as general semantics in 1933 with the publication of Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics.

In the context of hardware and software systems, formal verification is the act of proving or disproving the correctness of intended algorithms underlying a system with respect to a certain formal specification or property, using formal methods of mathematics.

The map–territory relation is the relationship between an object and a representation of that object, as in the relation between a geographical territory and a map of it. Polish-American scientist and philosopher Alfred Korzybski remarked that "the map is not the territory" and that "the word is not the thing", encapsulating his view that an abstraction derived from something, or a reaction to it, is not the thing itself. Korzybski held that many people do confuse maps with territories, that is, confuse conceptual models of reality with reality itself. These ideas are crucial to general semantics, a system Korzybski originated.

Samuel Ichiye Hayakawa was a Canadian-born American academic and politician of Japanese ancestry. A professor of English, he served as president of San Francisco State University and then as U.S. Senator from California from 1977 to 1983.

The study of how language influences thought has a long history in a variety of fields. There are two bodies of thought forming around this debate. One body of thought stems from linguistics and is known as the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis. There is a strong and a weak version of the hypothesis which argue for more or less influence of language on thought. The strong version, linguistic determinism, argues that without language there is and can be no thought while the weak version, linguistic relativity, supports the idea that there are some influences from language on thought. And on the opposing side, there are 'language of thought' theories (LOTH) which believe that public language is inessential to private thought. LOTH theories address the debate of whether thought is possible without language which is related to the question of whether language evolved for thought. These ideas are difficult to study because it proves challenging to parse the effects of culture versus thought versus language in all academic fields.

Linguistic determinism is the concept that language and its structures limit and determine human knowledge or thought, as well as thought processes such as categorization, memory, and perception. The term implies that people's native languages will affect their thought process and therefore people will have different thought processes based on their mother tongues.

Cognitive semantics is part of the cognitive linguistics movement. Semantics is the study of linguistic meaning. Cognitive semantics holds that language is part of a more general human cognitive ability, and can therefore only describe the world as people conceive of it. It is implicit that different linguistic communities conceive of simple things and processes in the world differently, not necessarily some difference between a person's conceptual world and the real world.

The semantic differential (SD) is a measurement scale designed to measure a person's subjective perception of, and affective reactions to, the properties of concepts, objects, and events by making use of a set of bipolar scales. The SD is used to assess one's opinions, attitudes, and values regarding these concepts, objects, and events in a controlled and valid way. Respondents are asked to choose where their position lies, on a set of scales with polar adjectives. Compared to other measurement scaling techniques such as Likert scaling, the SD can be assumed to be relatively reliable, valid, and robust.

Levels of Knowing and Existence: Studies in General Semantics is a textbook written by Professor Harry L. Weinberg that provides a broad overview of general semantics in language accessible to the layman.

Neo-Piagetian theories of cognitive development criticize and build upon Jean Piaget's theory of cognitive development.