Winemaking, wine-making, or vinification is the production of wine, starting with the selection of the fruit, its fermentation into alcohol, and the bottling of the finished liquid. The history of wine-making stretches over millennia. There is evidence that suggests that the earliest wine production took place in Georgia and Iran around 6000 to 5000 B.C. The science of wine and winemaking is known as oenology. A winemaker may also be called a vintner. The growing of grapes is viticulture and there are many varieties of grapes.

Fruit wines are fermented alcoholic beverages made from a variety of base ingredients ; they may also have additional flavors taken from fruits, flowers, and herbs. This definition is sometimes broadened to include any alcoholic fermented beverage except beer. For historical reasons, mead, cider, and perry are also excluded from the definition of fruit wine.

Red wine is a type of wine made from dark-colored grape varieties - The color of the wine can range from intense violet, typical of young wines, through to brick red for mature wines and brown for older red wines. The juice from most purple grapes is greenish-white, the red color coming from anthocyan pigments present in the skin of the grape. Much of the red wine production process involves extraction of color and flavor components from the grape skin.

Malolactic conversion is a process in winemaking in which tart-tasting malic acid, naturally present in grape must, is converted to softer-tasting lactic acid. Malolactic fermentation is most often performed as a secondary fermentation shortly after the end of the primary fermentation, but can sometimes run concurrently with it. The process is standard for most red wine production and common for some white grape varieties such as Chardonnay, where it can impart a "buttery" flavor from diacetyl, a byproduct of the reaction.

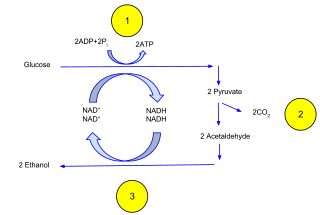

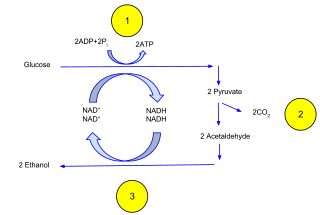

Ethanol fermentation, also called alcoholic fermentation, is a biological process which converts sugars such as glucose, fructose, and sucrose into cellular energy, producing ethanol and carbon dioxide as by-products. Because yeasts perform this conversion in the absence of oxygen, alcoholic fermentation is considered an anaerobic process. It also takes place in some species of fish where it provides energy when oxygen is scarce.

Kilju is the Finnish word for a mead-like homemade alcoholic beverage made from a source of carbohydrates, yeast, and water, making it both affordable and cheap to produce. The ABV is around 15–17%, and since it does not contain a sweet reserve it is completely dry. Crude product may be distilled into moonshine. Kilju intended for direct consumption is usually clarified and stabilized to avoid wine faults. It is a flax-colored alcoholic beverage with no discernible taste other than that of ethanol. It can be used as an ethanol base for drink mixers.

Maceration is the winemaking process where the phenolic materials of the grape—tannins, coloring agents (anthocyanins) and flavor compounds—are leached from the grape skins, seeds and stems into the must. To macerate is to soften by soaking, and maceration is the process by which the red wine receives its red color, since raw grape juice is clear-grayish in color. In the production of white wines, maceration is either avoided or allowed only in very limited manner in the form of a short amount of skin contact with the juice prior to pressing. This is more common in the production of varietals with less natural flavor and body structure like Sauvignon blanc and Sémillon. For Rosé, red wine grapes are allowed some maceration between the skins and must, but not to the extent of red wine production.

A wine fault is a sensory-associated (organoleptic) characteristic of a wine that is unpleasant, and may include elements of taste, smell, or appearance, elements that may arise from a "chemical or a microbial origin", where particular sensory experiences might arise from more than one wine fault. Wine faults may result from poor winemaking practices or storage conditions that lead to wine spoilage.

Secondary fermentation is a process commonly associated with winemaking, which entails a second period of fermentation in a different vessel than the one used to start the fermentation process. An example of this would be starting fermentation in a carboy or stainless steel tank and then moving it over to oak barrels. Rather than being a separate, second fermentation, this is most often one single fermentation period that is conducted in multiple vessels. However, the term does also apply to procedures that could be described as a second and distinct fermentation period.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to wine:

Sparkling wine production is the method of winemaking used to produce sparkling wine. The oldest known production of sparkling wine took place in 1531 with the ancestral method.

The process of fermentation in winemaking turns grape juice into an alcoholic beverage. During fermentation, yeasts transform sugars present in the juice into ethanol and carbon dioxide. In winemaking, the temperature and speed of fermentation are important considerations as well as the levels of oxygen present in the must at the start of the fermentation. The risk of stuck fermentation and the development of several wine faults can also occur during this stage, which can last anywhere from 5 to 14 days for primary fermentation and potentially another 5 to 10 days for a secondary fermentation. Fermentation may be done in stainless steel tanks, which is common with many white wines like Riesling, in an open wooden vat, inside a wine barrel and inside the wine bottle itself as in the production of many sparkling wines.

Sugars in wine are at the heart of what makes winemaking possible. During the process of fermentation, sugars from wine grapes are broken down and converted by yeast into alcohol (ethanol) and carbon dioxide. Grapes accumulate sugars as they grow on the grapevine through the translocation of sucrose molecules that are produced by photosynthesis from the leaves. During ripening the sucrose molecules are hydrolyzed (separated) by the enzyme invertase into glucose and fructose. By the time of harvest, between 15 and 25% of the grape will be composed of simple sugars. Both glucose and fructose are six-carbon sugars but three-, four-, five- and seven-carbon sugars are also present in the grape. Not all sugars are fermentable, with sugars like the five-carbon arabinose, rhamnose and xylose still being present in the wine after fermentation. Very high sugar content will effectively kill the yeast once a certain (high) alcohol content is reached. For these reasons, no wine is ever fermented completely "dry". Sugar's role in dictating the final alcohol content of the wine sometimes encourages winemakers to add sugar during winemaking in a process known as chaptalization solely in order to boost the alcohol content – chaptalization does not increase the sweetness of a wine.

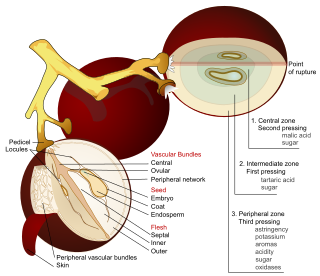

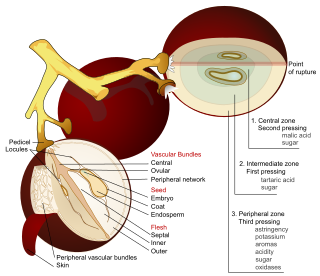

The acids in wine are an important component in both winemaking and the finished product of wine. They are present in both grapes and wine, having direct influences on the color, balance and taste of the wine as well as the growth and vitality of yeast during fermentation and protecting the wine from bacteria. The measure of the amount of acidity in wine is known as the “titratable acidity” or “total acidity”, which refers to the test that yields the total of all acids present, while strength of acidity is measured according to pH, with most wines having a pH between 2.9 and 3.9. Generally, the lower the pH, the higher the acidity in the wine. There is no direct connection between total acidity and pH. In wine tasting, the term “acidity” refers to the fresh, tart and sour attributes of the wine which are evaluated in relation to how well the acidity balances out the sweetness and bitter components of the wine such as tannins. Three primary acids are found in wine grapes: tartaric, malic, and citric acids. During the course of winemaking and in the finished wines, acetic, butyric, lactic, and succinic acids can play significant roles. Most of the acids involved with wine are fixed acids with the notable exception of acetic acid, mostly found in vinegar, which is volatile and can contribute to the wine fault known as volatile acidity. Sometimes, additional acids, such as ascorbic, sorbic and sulfurous acids, are used in winemaking.

This glossary of winemaking terms lists some of terms and definitions involved in making wine, fruit wine, and mead.

In winemaking, pressing is the process where juice is extracted from the grapes with the aid of a wine-press, by hand, or even by the weight of the grape berries and clusters. Historically, intact grape clusters were trodden by feet but in most wineries today the grapes are sent through a crusher/destemmer, which removes the individual grape berries from the stems and breaks the skins, releasing some juice, prior to being pressed. There are exceptions, such as the case of sparkling wine production in regions such as Champagne where grapes are traditionally whole-cluster pressed with stems included to produce a lighter must that is low in phenolics.

In winemaking, clarification and stabilization are the processes by which insoluble matter suspended in the wine is removed before bottling. This matter may include dead yeast cells (lees), bacteria, tartrates, proteins, pectins, various tannins and other phenolic compounds, as well as pieces of grape skin, pulp, stems and gums. Clarification and stabilization may involve fining, filtration, centrifugation, flotation, refrigeration, pasteurization, and/or barrel maturation and racking.

In viticulture, ripeness is the completion of the ripening process of wine grapes on the vine which signals the beginning of harvest. What exactly constitutes ripeness will vary depending on what style of wine is being produced and what the winemaker and viticulturist personally believe constitutes ripeness. Once the grapes are harvested, the physical and chemical components of the grape which will influence a wine's quality are essentially set so determining the optimal moment of ripeness for harvest may be considered the most crucial decision in winemaking.

The role of yeast in winemaking is the most important element that distinguishes wine from fruit juice. In the absence of oxygen, yeast converts the sugars of the fruit into alcohol and carbon dioxide through the process of fermentation. The more sugars in the grapes, the higher the potential alcohol level of the wine if the yeast are allowed to carry out fermentation to dryness. Sometimes winemakers will stop fermentation early in order to leave some residual sugars and sweetness in the wine such as with dessert wines. This can be achieved by dropping fermentation temperatures to the point where the yeast are inactive, sterile filtering the wine to remove the yeast or fortification with brandy or neutral spirits to kill off the yeast cells. If fermentation is unintentionally stopped, such as when the yeasts become exhausted of available nutrients and the wine has not yet reached dryness, this is considered a stuck fermentation.

Yeast assimilable nitrogen or YAN is the combination of free amino nitrogen (FAN), ammonia (NH3) and ammonium (NH4+) that is available for a yeast, e.g. the wine yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, to use during fermentation. Outside of the fermentable sugars glucose and fructose, nitrogen is the most important nutrient needed to carry out a successful fermentation that doesn't end prior to the intended point of dryness or sees the development of off-odors and related wine faults. To this extent winemakers will often supplement the available YAN resources with nitrogen additives such as diammonium phosphate (DAP).