Related Research Articles

An omen is a phenomenon that is believed to foretell the future, often signifying the advent of change. It was commonly believed in ancient times, and still believed by some today, that omens bring divine messages from the gods.

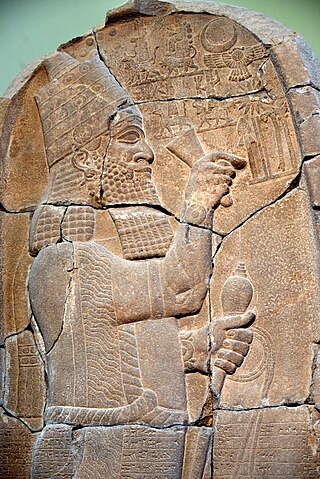

Esarhaddon, also spelled Essarhaddon, Assarhaddon and Ashurhaddon was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 681 BC to 669 BC. The third king of the Sargonid dynasty, Esarhaddon is most famous for his conquest of Egypt in 671 BC, which made his empire the largest the world had ever seen, and for his reconstruction of Babylon, which had been destroyed by his father.

Ashurbanipal was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BC to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king of Assyria. Ashurbanipal inherited the throne as the favored heir of his father Esarhaddon; his 38-year reign was among the longest of any Assyrian king. Though sometimes regarded as the apogee of ancient Assyria, his reign also marked the last time Assyrian armies waged war throughout the ancient Near East and the beginning of the end of Assyrian dominion over the region.

Sîn-šar-iškun was the penultimate king of Assyria, reigning from the death of his brother and predecessor Aššur-etil-ilāni in 627 BC to his own death at the Fall of Nineveh in 612 BC.

Šamaš-šuma-ukin, was king of Babylon as a vassal of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 668 BC to his death in 648. Born into the Assyrian royal family, Šamaš-šuma-ukin was the son of the Neo-Assyrian king Esarhaddon and the elder brother of Esarhaddon's successor Ashurbanipal.

Aššur-etil-ilāni, also spelled Ashur-etel-ilani and Ashuretillilani, was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 631 BC to 627 BC. Aššur-etil-ilāni is an obscure figure with a brief reign from which few inscriptions survive. Because of this lack of sources, very little concrete information about the king and his reign can be deduced.

Babylonian astrology was the first known organized system of astrology, arising in the second millennium BC.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, North Africa and East Mediterranean throughout much of the 9th to 7th centuries BC, becoming the largest empire in history up to that point. Because of its geopolitical dominance and ideology based in world domination, the Neo-Assyrian Empire has been described as the first world empire in history. It influenced other empires of the ancient world culturally, administratively, and militarily, including the Neo-Babylonians, the Achaemenids, and the Seleucids. At its height, the empire was the strongest military power in the world and ruled over all of Mesopotamia, the Levant and Egypt, as well as parts of Anatolia, Arabia and modern-day Iran and Armenia.

Adad-apla-iddina, typically inscribed in cuneiform mdIM-DUMU.UŠ-SUM-na, mdIM-A-SUM-na or dIM-ap-lam-i-din-[nam] meaning the storm god “Adad has given me an heir”, was the 8th king of the 2nd Dynasty of Isin and the 4th Dynasty of Babylon and ruled c. 1064–1043. He was a contemporary of the Assyrian King Aššur-bêl-kala and his reign was a golden age for scholarship.

The NAM-BÚR-BI are magical texts which take the form of incantations. They were named for a series of prophylactic Babylonian and Assyrian rituals to avert inauspicious portents before they took on tangible form. At the core of these rituals was an appeal by the subject of the sinister omen to the divine judicial court to obtain a change to his impending fate. From the corpus of Babylonian-Assyrian religious texts that has survived, there are approximately one hundred and forty texts, many preserved in several copies, to which this label may be applied.

Akkad was the capital of the Akkadian Empire, which was the dominant political force in Mesopotamia during a period of about 150 years in the last third of the 3rd millennium BC.

Naqiʾa or Naqia (Akkadian: Naqīʾa, also known as Zakūtu, was a wife of the Assyrian king Sennacherib and the mother of his son and successor Esarhaddon. Naqiʾa is the best documented woman in the history of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and she reached an unprecedented level of prominence and public visibility; she was perhaps the most influential woman in Assyrian history. She is one of the few ancient Assyrian women to be depicted in artwork, to commission her own building projects, and to be granted laudatory epithets in letters by courtiers. She is also the only known ancient Assyrian figure other than kings to write and issue a treaty.

The timeline of ancient Assyria can be broken down into three main eras: the Old Assyrian period, Middle Assyrian Empire, and Neo-Assyrian Empire. Modern scholars typically also recognize an Early period preceding the Old Assyrian period and a post-imperial period succeeding the Neo-Assyrian period.

The Sargonid dynasty was the final ruling dynasty of Assyria, ruling as kings of Assyria during the Neo-Assyrian Empire for just over a century from the ascent of Sargon II in 722 BC to the fall of Assyria in 609 BC. Although Assyria would ultimately fall during their rule, the Sargonid dynasty ruled the country during the apex of its power and Sargon II's three immediate successors Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal are generally regarded as three of the greatest Assyrian monarchs. Though the dynasty encompasses seven Assyrian kings, two vassal kings in Babylonia and numerous princes and princesses, the term Sargonids is sometimes used solely for Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal.

Šērūʾa-ēṭirat, called Saritrah in later Aramaic texts), was an ancient Assyrian princess of the Sargonid dynasty, the eldest daughter of Esarhaddon and the older sister of his son and successor Ashurbanipal. She is the only one of Esarhaddon's daughters to be known by name and inscriptions listing the royal children suggest that she outranked several of her brothers, such as her younger brother Aššur-mukin-paleʾa, but ranked below the crown princes Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin. Her importance could be explained by her possibly being the oldest of all Esarhaddon's children.

Ešarra-ḫammat was a queen of the Neo-Assyrian Empire as the primary consort of Esarhaddon. Ešarra-ḫammat had been married to Esarhaddon for over a decade by the time he became king, having married him c. 695 BC. Few sources from Ešarra-ḫammat's lifetime that mention her are known and she is thus chiefly known from sources dating to after her death in February 672 BC, an event which deeply affected Esarhaddon. Esarhaddon had a great mausoleum constructed for her, unusual for burials of Assyrian queens, and had her death recorded in the Babylonian Chronicles. Ešarra-ḫammat might have been the mother of Esarhaddon's most prominent children, i.e. the daughter Šērūʾa-ēṭirat and the sons Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin.

The Assyrian conquest of Egypt covered a relatively short period of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 673 to 663 BCE. The conquest of Egypt not only placed a land of great cultural prestige under Assyrian rule but also brought the Neo-Assyrian Empire to its greatest extent.

Šarru-lu-dari, meaning "May the king be everlasting") was a king of Ascalon during the reign of the Neo-Assyrian emperors Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanipal. His father was named Rukibtu, who ruled Ascalon before Šarru-lu-dari's predecessor, the rebellious king Sidqa. Though he was implicitly a Philistine, his name is uniquely Assyrian.

The Sasî movement was a set of conspiracies and plots directed against the Assyrian king Esarhaddon in 671–670 BCE, each in some way involving Sasî, a high-ranking official of dubious loyalty. Aimed at dethroning Esarhaddon, the conspiracies involved the simultaneous proclamation of perhaps as many as three rival contenders for the throne, including Sasî himself. Conspirators were active throughout the Assyrian Empire, apparently concentrated around the city of Harran but also operating in Babylonia and even in central Assyria.

Ishtar of Arbela or the Lady of Arbela was a prominent goddess of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. She was the tutelary goddess of the city of Arbela as well as a patron goddess of the king. She was clearly distinct from other 'Ishtar' goddesses in religious worship. For example, in the city of Assur, she had a shrine separate from Ishtar of Assur, and Ishtar of Nineveh had a separate cult from either deity in Assur as well as a presence in Arbela. Similarly, they are usually distinguished from each other in hymns, prophetic texts, and treaties. In his Hymn to the Ištars of Nineveh and Arbela, King Ashurbanipal refers to the pair as 'my Ishtars' and uses plural language throughout, as well as ascribing them different functions in supporting the king. However, some poetic and prophetic texts appear to not draw sharp lines between their identities and refer to an unspecified "Ishtar".

References

- ↑ Radner, Karen. The Trials of Esarhaddon: The Conspiracy of 670 BC. University College London, 2004.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Parpola, Simo. Letters from Assyrian Scholars to the Kings Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal. Verlag Butzon & Bercker Kevelaer, 1983.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Jones, Christopher W. Power and Elite Competition in the Neo-Assyrian Empire 745-612 BC. Columbia University, 2021