Related Research Articles

Martin Luther King Jr. was an American Baptist minister, activist, and political philosopher who was one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968. A black church leader and a son of early civil rights activist and minister Martin Luther King Sr., King advanced civil rights for people of color in the United States through the use of nonviolent resistance and nonviolent civil disobedience against Jim Crow laws and other forms of legalized discrimination.

The University of California, Davis School of Law is the professional graduate law school of the University of California, Davis. The school received ABA approval in 1968. It joined the Association of American Law Schools (AALS) in 1968.

James Morris Lawson Jr. was an American activist and university professor. He was a leading theoretician and tactician of nonviolence within the Civil Rights Movement. During the 1960s, he served as a mentor to the Nashville Student Movement and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He was expelled from Vanderbilt University for his civil rights activism in 1960, and later served as a pastor in Los Angeles for 25 years.

Morehouse College is a private historically Black, men's, liberal arts college in Atlanta, Georgia. Anchored by its main campus of 61 acres (25 ha) near Downtown Atlanta, the college has a variety of residential dorms and academic buildings east of Ashview Heights. Along with Spelman College, Clark Atlanta University, and the Morehouse School of Medicine, the college is a member of the Atlanta University Center consortium.

Albert Anderson Raby was a teacher at Chicago's Hess Upper Grade Center who secured the support of Martin Luther King Jr. to desegregate schools and housing in Chicago between 1965 and 1967. Raby was a part of the civil rights movement and helped create the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations (CCCO), the mission of the CCCO was to end segregation in Chicago schools. Raby tried to stay out of the media and public eye, which limited information known about him.

Alberta Christine Williams King was an American civil rights organizer best known as the wife of Martin Luther King Sr., and as the mother of Martin Luther King Jr. She was the choir director of the Ebenezer Baptist Church. She was shot and killed in the church by 23-year-old Marcus Wayne Chenault six years after the assassination of her eldest son Martin Luther King Jr.

The Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park covers about 35 acres (0.14 km2) and includes several sites in Atlanta, Georgia related to the life and work of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. Within the park is his boyhood home, and Ebenezer Baptist Church — the church where King was baptized and both he and his father, Martin Luther King Sr., were pastors — as well as, the grave site of King, Jr., and his wife, civil rights activist Coretta Scott King.

Emeritus Professor Stuart Rees AM is an Australian academic, human rights activist and author who is the founder of the Sydney Peace Foundation and Emeritus Professor at the Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Sydney in Australia.

Jack O'Dell was an African-American activist writer and communist, best known for his role in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. During World War II, he was an organizer for the National Maritime Union. He was also involved with the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) as well as working with Martin Luther King Jr.

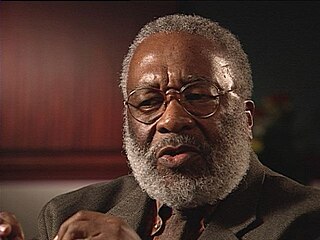

Vincent Gordon Harding was an African-American pastor, historian, and scholar of various topics with a focus on American religion and society. A social activist, he was perhaps best known for his work with and writings about Martin Luther King Jr., whom Harding knew personally. Besides having authored numerous books such as There Is A River, Hope and History, and Martin Luther King: The Inconvenient Hero, he served as co-chairperson of the social unity group Veterans of Hope Project and as Professor of Religion and Social Transformation at Iliff School of Theology in Denver, Colorado. When Harding died on May 19, 2014, his daughter, Rachel Elizabeth Harding, publicly eulogized him on the Veterans of Hope Project website.

Clayborne Carson is an American academic who was a professor of history at Stanford University and director of the Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute. Since 1985, he has directed the Martin Luther King Papers Project, a long-term project to edit and publish the papers of Martin Luther King Jr.

Willie Christine King Farris was an American teacher and civil rights activist. King was the sister of Martin Luther King Jr. She taught at Spelman College and was the author of several books and was a public speaker on various topics, including the King family, multicultural education, and teaching.

The National Gandhi Memorial Trust also called the Gandhi Qaumi Yaadgar Fund, is a memorial trust run by the Central Government of India established to commemorate the life of Mahatma Gandhi. It funds the maintenance of various places associated with Mahatma Gandhi's activities during India's freedom movement, and is also a leading producer of literature on Gandhi and Gandhian thought in India.

Clarence Benjamin Jones is an American lawyer and the former personal counsel, advisor, draft speech writer and close friend of Martin Luther King Jr. He is a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor. Jones is a scholar in residence at the Martin Luther King Jr. Institute at Stanford University. He is the author of What Would Martin Say? and Behind the Dream: The Making of the Speech that Transformed a Nation. His book Last of the Lions was released on August 1, 2023. Jones currently serves as Chairman of the non-profit Spill the Honey Foundation.

Ravindra Kumar is a Political Scientist, Peace Educator, an Indologist, a Humanist, Cultural Anthropologist and a former Vice-Chancellor of CCS University, Meerut (India).

The sermons and speeches of Martin Luther King Jr., comprise an extensive catalog of American writing and oratory – some of which are internationally well-known, while others remain unheralded and await rediscovery.

Samuel DeWitt Proctor was an American minister, educator, and humanitarian. An African-American church and higher education leader, he was active in the Civil Rights Movement and is perhaps best known as a mentor and friend of Martin Luther King Jr.

Michael K. Honey is an American historian, Guggenheim Fellow and Haley Professor of Humanities at the University of Washington Tacoma in the United States, where he teaches African-American, civil rights and labor history.

Lawrence Edward Carter, Sr. is an American historian, professor, author, and civil rights expert. He is Professor of Religion, College Archivist and Curator at Morehouse College as well as the Dean of the Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel at Morehouse. Carter is also the founder of the Martin Luther King Jr. Chapel Assistants Pre-seminarians Program, and director of the Martin Luther King Jr. College of Pastoral Leadership.

Professor Emmanuel Gyimah-Boadi is a Ghanaian political scientist and the co-founder of the Afrobarometer, a pan-African research project that surveys public attitude on political, social and economic reforms across African countries. He was the CEO of Afrobarometer from 2008 to 2021. He is now the chair of its board of directors.

References

- King R. & Ed. Inst. (2019) King's India trip, Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University. Accessed 2021-05-16.

- King R. & Ed. Inst. (2019), Kapoor biography, The M. L. King Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University. Accessed 2021-04-30.