Harold Godwinson, also called Harold II, was the last crowned Anglo-Saxon English king. Harold reigned from 6 January 1066 until his death at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066, the decisive battle of the Norman Conquest. Harold's death marked the end of Anglo-Saxon rule over England. He was succeeded by William the Conqueror.

Edward the Confessor was an Anglo-Saxon English king and saint. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 until his death in 1066.

Eadburh was the daughter of King Edward the Elder of England and his third wife, Eadgifu of Kent. She lived most of her life as a nun known for her singing ability. Most of the information about her comes from hagiographies written several centuries after her life. She was canonised twelve years after her death and there are a small number of churches dedicated to her, most of which are located near Worcestershire, where she lived.

Theobald of Bec was a Norman archbishop of Canterbury from 1139 to 1161. His exact birth date is unknown. Some time in the late 11th or early 12th century Theobald became a monk at the Abbey of Bec, rising to the position of abbot in 1137. King Stephen of England chose him to be Archbishop of Canterbury in 1138. Canterbury's claim to primacy over the Welsh ecclesiastics was resolved during Theobald's term of office when Pope Eugene III decided in 1148 in Canterbury's favour. Theobald faced challenges to his authority from a subordinate bishop, Henry of Blois, Bishop of Winchester and King Stephen's younger brother, and his relationship with King Stephen was turbulent. On one occasion Stephen forbade him from attending a papal council, but Theobald defied the king, which resulted in the confiscation of his property and temporary exile. Theobald's relations with his cathedral clergy and the monastic houses in his archdiocese were also difficult.

Thurstan or Turstin of Bayeux was a medieval Archbishop of York, the son of a priest. He served kings William II and Henry I of England before his election to the see of York in 1114. Once elected, his consecration was delayed for five years while he fought attempts by the Archbishop of Canterbury to assert primacy over York. Eventually, he was consecrated by the pope instead and allowed to return to England. While archbishop, he secured two new suffragan bishops for his province. When Henry I died, Thurstan supported Henry's nephew Stephen of Blois as king. Thurstan also defended the northern part of England from invasion by the Scots, taking a leading part in organising the English forces at the Battle of the Standard (1138). Shortly before his death, Thurstan resigned from his see and took the habit of a Cluniac monk.

Edith of Wessex was Queen of England through her marriage to Edward the Confessor from 1045 until Edward's death in 1066. Unlike most English queens in the 10th and 11th centuries, she was crowned. The principal source on her life is a work she herself commissioned, the Vita Ædwardi Regis or the Life of King Edward who rests at Westminster, which is inevitably biased.

Siward or Sigurd was an important earl of 11th-century northern England. The Old Norse nickname Digri and its Latin translation Grossus are given to him by near-contemporary texts. It is possible Siward may have been of Scandinavian or Anglo-Scandinavian origin, perhaps a relative of Earl Ulf, although this is speculative. He emerged as a regional strongman in England during the reign of Cnut. Cnut was a Scandinavian ruler who conquered most of England in the 1010s, and Siward was one of many Scandinavians who came to England in the aftermath, rising to become sub-ruler of most of northern England. From 1033 at the latest, he was in control of southern Northumbria, present-day Yorkshire, governing as earl on Cnut's behalf.

Gilbert Crispin was a Christian author and Anglo-Norman monk, appointed by Archbishop Lanfranc in 1085 to be the abbot, proctor and servant of Westminster Abbey, England. Gilbert became the third Norman Abbot of Westminster to be appointed after the Norman Conquest, succeeding Abbot Vitalis of Bernay.

Gyrth Godwinson was the fourth son of Earl Godwin, and thus a younger brother of Harold Godwinson. He went with his eldest brother Sweyn into exile to Flanders in 1051, but unlike Sweyn he was able to return with the rest of the clan the following year. Along with his brothers Harold and Tostig, Gyrth was present at his father's death-bed.

Sweyn Godwinson, also spelled Swein, was the eldest son of Earl Godwin of Wessex, and brother of Harold II of England.

Vitalis of Savigny was the canonized founder of Savigny Abbey and of the Congregation of Savigny (1112).

David Scotus or David the Scot was a Gaelic chronicler who died in 1139. He was a Welsh or Irish cleric who was Bishop of Bangor from 1120 to 1138.

John Flete was an English monk and ecclesiastical historian who documented the history and abbots of Westminster Abbey.

Goscelin of Saint-Bertin was a Benedictine hagiographical writer. He was a Fleming or Brabantian by birth and became a monk of St Bertin's at Saint-Omer before travelling to England to take up a position in the household of Herman, Bishop of Ramsbury in Wiltshire (1058–78). During his time in England, he stayed at many monasteries and wherever he went collected materials for his numerous hagiographies of English saints.

Ælfgifu of York was the first wife of Æthelred the Unready, King of the English; as such, she was Queen of the English from their marriage in the 980s until her death in 1002. They had many children together, including Edmund Ironside. It is most probable that Ælfgifu was a daughter of Thored, Earl of southern Northumbria and his wife, Hilda.

Osbert of Clare was a monk, elected prior of Westminster Abbey and briefly abbot. He was a prolific writer of letters, and hagiographer.

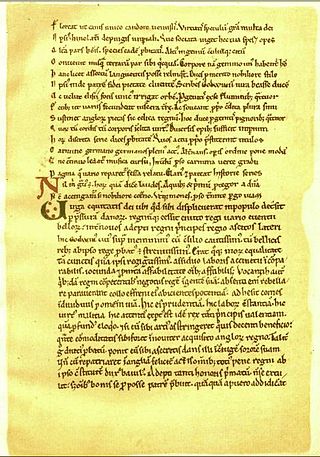

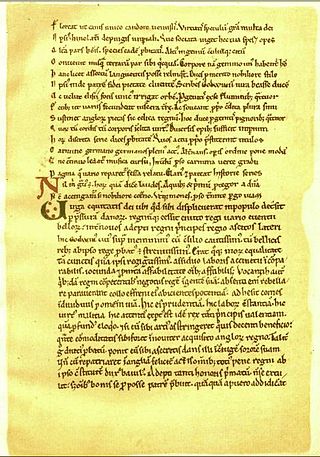

The Vita Ædwardi Regis qui apud Westmonasterium Requiescit or simply Vita Ædwardi Regis is a Latin biography of King Edward the Confessor completed by an anonymous author c. 1067 and suspected of having been commissioned by Queen Edith, Edward's wife. It survives in one manuscript, dated c. 1100, now in the British Library. The author is unknown, but was a servant of the queen and probably a Fleming. The most likely candidates are Goscelin and Folcard, monks of St Bertin Abbey in St Omer.

Gervase of Blois was the Abbot of Westminster in England between 1138 and around 1157. Historically, Gervase has a bad reputation for mismanaging the abbey, although modern historians have re-evaluated his performance as abbot.

Vitalis of Creuilly or Vitalis of Bernay was a Benedictine monk from Normandy. Sources on his life include the early 15th century history of the Abbey by John Flete and the 1751 An history of the Church of St. Peter, Westminster, commonly called Westminster Abbey by Richard Widmore.

The English embassy to Rome in 1061 was a deputation sent by king Edward the Confessor to the pope, Nicholas II, to deal with various ecclesiastical matters, particularly the ordination of Giso, Bishop of Wells, Walter, Bishop of Hereford, and Ealdred, Archbishop of York. They travelled to Rome under the protection of Tostig, earl of Northumbria and his brother Gyrth. Ealdred was initially refused ordination by the pope because he was adjudged guilty of pluralism and other breaches of canon law, and the embassy received a further setback when they were despoiled by robbers as they began their journey home. When they returned indignantly to Rome, however, Ealdred was granted the archbishopric after all, and the party was able to make its way home to England with almost all its objectives achieved.