A sundial is a horological device that tells the time of day when direct sunlight shines by the apparent position of the Sun in the sky. In the narrowest sense of the word, it consists of a flat plate and a gnomon, which casts a shadow onto the dial. As the Sun appears to move through the sky, the shadow aligns with different hour-lines, which are marked on the dial to indicate the time of day. The style is the time-telling edge of the gnomon, though a single point or nodus may be used. The gnomon casts a broad shadow; the shadow of the style shows the time. The gnomon may be a rod, wire, or elaborately decorated metal casting. The style must be parallel to the axis of the Earth's rotation for the sundial to be accurate throughout the year. The style's angle from horizontal is equal to the sundial's geographical latitude.

A diptych is any object with two flat plates which form a pair, often attached by a hinge. For example, the standard notebook and school exercise book of the ancient world was a diptych consisting of a pair of such plates that contained a recessed space filled with wax. Writing was accomplished by scratching the wax surface with a stylus. When the notes were no longer needed, the wax could be slightly heated and then smoothed to allow reuse. Ordinary versions had wooden frames, but more luxurious diptychs were crafted with more expensive materials.

A gnomon is the part of a sundial that casts a shadow. The term is used for a variety of purposes in mathematics and other fields.

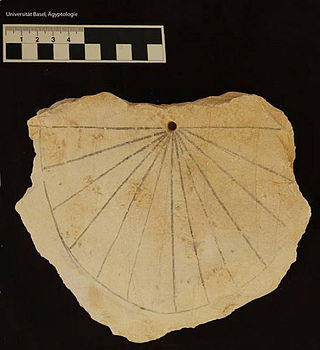

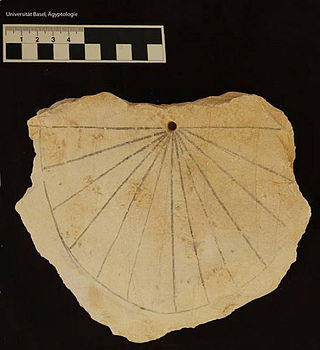

The scaphe was a sundial said to have been invented by Aristarchus of Samos. There are no original works still in existence by Aristarchus, but the adjacent picture is an image of what it might have looked like; only his would have been made of stone. It consisted of a hemispherical bowl which had a vertical gnomon placed inside it, with the top of the gnomon level with the edge of the bowl. Twelve gradations inscribed perpendicular to the hemisphere indicated the hour of the day.

The Ambassadors is a 1533 painting by Hans Holbein the Younger. Also known as Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve, after the two people it portrays, it was created in the Tudor period, in the same year Elizabeth I was born. Franny Moyle speculates that Elizabeth's mother, Anne Boleyn, then Queen of England, might have commissioned it as a gift for Jean de Dinteville, the French ambassador, portrayed on the left. De Selve was a Catholic Bishop.

The MarsDial is a sundial that was devised for missions to Mars. It is used to calibrate the Pancam cameras of the Mars landers. MarsDials were placed on the Spirit and Opportunity Mars rovers, inscribed with the words "Two worlds, One sun" and the word "Mars" in 22 languages. The MarsDial can function as a gnomon, the stick or other vertical part of a sundial. The length and direction of the shadow cast by the stick allows observers to calculate the time of day. The sundial can also be used to tell which way is North, and to overcome the limitations of a magnetic north different from a true north.

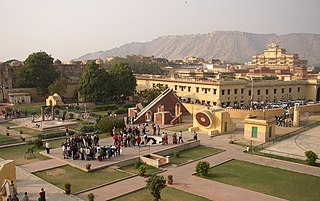

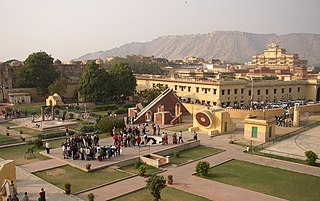

The Jantar Mantar is a collection of 19 astronomical instruments built by the Rajput king Sawai Jai Singh, the founder of Jaipur, Rajasthan. The monument was completed in 1734. It features the world's largest stone sundial, and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is near City Palace and Hawa Mahal. The instruments allow the observation of astronomical positions with the naked eye. The observatory is an example of the Ptolemaic positional astronomy which was shared by many civilizations.

Gnomonics is the study of the design, construction and use of sundials.

Mount Cuba Astronomical Observatory is an astronomical observatory is located at 1610 Hillside Mill Road, Greenville, Delaware, United States. This observatory is home to a 0.6-meter telescope used by the Delaware Astronomical Society, the University of Delaware, and the Whole Earth Telescope. The DAS is composed of interested amateurs and engages in astronomy education and public outreach. Meetings are held the third Tuesday of each month at the Mt. Cuba Astronomical Observatory.

Analemmatic sundials are a type of horizontal sundial that has a vertical gnomon and hour markers positioned in an elliptical pattern. The gnomon is not fixed and must change position daily to accurately indicate time of day. Hence there are no hour lines on the dial and the time of day is read only on the ellipse. As with most sundials, analemmatic sundials mark solar time rather than clock time.

Man Enters the Cosmos is a cast bronze sculpture by Henry Moore located on the Lake Michigan lakefront outside the Adler Planetarium in the Museum Campus area of downtown Chicago, Illinois.

The ancient Egyptians were one of the first cultures to widely divide days into generally agreed-upon equal parts, using early timekeeping devices such as sundials, shadow clocks, and merkhets . Obelisks were also used by reading the shadow that they make. The clock was split into daytime and nighttime, and then into smaller hours.

The Gnomon of Saint-Sulpice is an astronomical measurement device located in the Church of Saint-Sulpice in Paris, France. It is a gnomon, a device designed to cast a shadow on the ground in order to determine the position of the sun in the sky. In early modern times, other gnomons were also built in several Italian and French churches in order to better calculate astronomical events. Those churches are Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, San Petronio in Bologna, and the Church of the Certosa in Rome. These gnomons ultimately fell into disuse with the advent of powerful telescopes.

A sundial is a device that indicates time by using a light spot or shadow cast by the position of the Sun on a reference scale. As the Earth turns on its polar axis, the sun appears to cross the sky from east to west, rising at sun-rise from beneath the horizon to a zenith at mid-day and falling again behind the horizon at sunset. Both the azimuth (direction) and the altitude (height) can be used to create time measuring devices. Sundials have been invented independently in every major culture and became more accurate and sophisticated as the culture developed.

Sundial, Boy With Spider is an outdoor sculpture and functional sundial by American artist Willard Dryden Paddock (1873–1956). It is located within the Oldfields estate on the grounds of the Indianapolis Museum of Art (IMA), in Indianapolis, Indiana, United States. The bronze sculpture, cast by the Gorham Manufacturing Company, depicts a boy sitting cross-legged with an open scroll in his lap.

The Whitehurst & Son sundial was produced in Derby in 1812 by the nephew of John Whitehurst. It is a fine example of a precision sundial telling local apparent time with a scale to convert this to local mean time, and is accurate to the nearest minute. The sundial is now housed in the Derby Museum and Art Gallery.

A London dial in the broadest sense can mean any sundial that is set for 51°30′ N, but more specifically refers to a engraved brass horizontal sundial with a distinctive design. London dials were originally engraved by scientific instrument makers. The trade was heavily protected by the system of craft guilds.

A schema for horizontal dials is a set of instructions used to construct horizontal sundials using compass and straightedge construction techniques, which were widely used in Europe from the late fifteenth century to the late nineteenth century. The common horizontal sundial is a geometric projection of an equatorial sundial onto a horizontal plane.

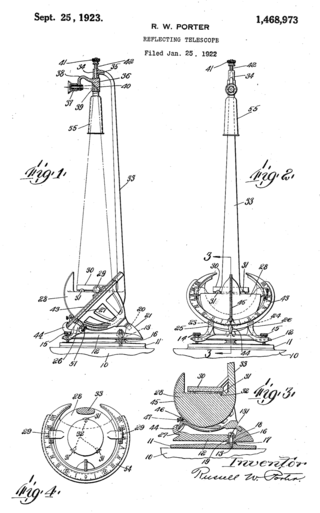

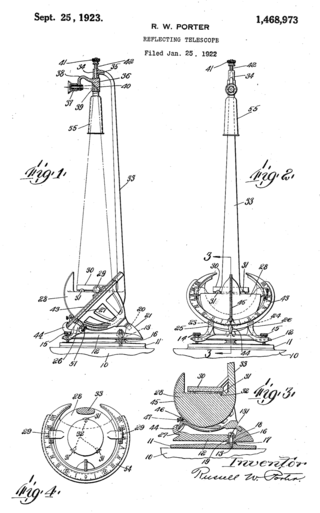

The Porter Garden Telescope was an innovative ornamental telescope for the garden designed by Russell W. Porter and commercialized by Jones & Lamson Machine Company at the beginning of the 1920s in the United States.