Emergency contraception (EC) is a birth control measure, used after sexual intercourse to prevent pregnancy.

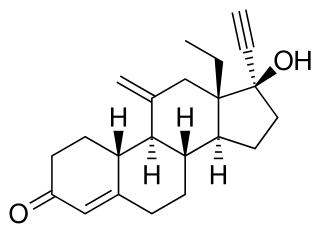

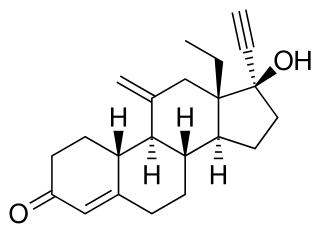

Levonorgestrel is a hormonal medication which is used in a number of birth control methods. It is combined with an estrogen to make combination birth control pills. As an emergency birth control, sold under the brand names Plan B One-Step and Julie, among others, it is useful within 72 hours of unprotected sex. The more time that has passed since sex, the less effective the medication becomes, and it does not work after pregnancy (implantation) has occurred. Levonorgestrel works by preventing ovulation or fertilization from occurring. It decreases the chances of pregnancy by 57–93%. In an intrauterine device (IUD), such as Mirena among others, it is effective for the long-term prevention of pregnancy. A levonorgestrel-releasing implant is also available in some countries.

Levonorgestrel-releasing implant, sold under the brand name Jadelle among others, are devices that release levonorgestrel for birth control. It is one of the most effective forms of birth control with a one-year failure rate around 0.05%. The device is placed under the skin and lasts for up to five years. It may be used by women who have a history of pelvic inflammatory disease and therefore cannot use an intrauterine device. Following removal, fertility quickly returns.

A contraceptive patch, also known as "the patch", is a transdermal patch applied to the skin that releases synthetic oestrogen and progestogen hormones to prevent pregnancy. They have been shown to be as effective as the combined oral contraceptive pill with perfect use, and the patch may be more effective in typical use.

Frances Kathleen Oldham Kelsey was a Canadian-American pharmacologist and physician. As a reviewer for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), she refused to authorize thalidomide for market because she had concerns about the lack of evidence regarding the drug's safety. Her concerns proved to be justified when it was shown that thalidomide caused serious birth defects. Kelsey's career intersected with the passage of laws strengthening FDA oversight of pharmaceuticals. Kelsey was the second woman to receive the President's Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service, awarded to her by John F. Kennedy in 1962.

A hormonal intrauterine device (IUD), also known as an intrauterine system (IUS) with progestogen and sold under the brand name Mirena among others, is an intrauterine device that releases a progestogenic hormonal agent such as levonorgestrel into the uterus. It is used for birth control, heavy menstrual periods, and to prevent excessive build of the lining of the uterus in those on estrogen replacement therapy. It is one of the most effective forms of birth control with a one-year failure rate around 0.2%. The device is placed in the uterus and lasts three to eight years. Fertility often returns quickly following removal.

David Aaron Kessler is an American pediatrician, attorney, author, and administrator serving as Chief Science Officer of the White House COVID-19 Response Team since 2021. Kessler was the commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) from November 8, 1990, to February 28, 1997. He co-chaired the Biden-Harris transition’s COVID-19 Advisory Board from November 2020 to January 2021 and was the head of Operation Warp Speed, the U.S. government program to accelerate the development of COVID-19 vaccines and other treatments, from January to February 2021.

The Population Council is an international, nonprofit, non-governmental organization. The Council conducts research in biomedicine, social science, and public health and helps build research capacities in developing countries. One-third of its research relates to HIV and AIDS; while its other major program areas are still linked to its early foundation in reproductive health and its relation to poverty, youth, and gender. For example, the Population Council strives to teach boys that they can be involved in contraceptive methods regardless of stereotypes that limit male responsibility in child bearing. The organization held the license for Norplant contraceptive implant, and now holds the license for Mirena intrauterine system. The Population Council also publishes the journal Population and Development Review, which reports scientific research on the interrelationships between population and socioeconomic development. It also provides a forum for discussion on related issues of public policy and Studies in Family Planning, which focuses on public health, social science, and biomedical research involving sexual and reproductive health, fertility, and family planning.

Hormonal contraception refers to birth control methods that act on the endocrine system. Almost all methods are composed of steroid hormones, although in India one selective estrogen receptor modulator is marketed as a contraceptive. The original hormonal method—the combined oral contraceptive pill—was first marketed as a contraceptive in 1960. In the ensuing decades, many other delivery methods have been developed, although the oral and injectable methods are by far the most popular. Hormonal contraception is highly effective: when taken on the prescribed schedule, users of steroid hormone methods experience pregnancy rates of less than 1% per year. Perfect-use pregnancy rates for most hormonal contraceptives are usually around the 0.3% rate or less. Currently available methods can only be used by women; the development of a male hormonal contraceptive is an active research area.

Etonogestrel is a medication which is used as a means of birth control for women. It is available as an implant placed under the skin of the upper arm under the brand names Nexplanon and Implanon. It is a progestin that is also used in combination with ethinylestradiol, an estrogen, as a vaginal ring under the brand names NuvaRing and Circlet. Etonogestrel is effective as a means of birth control and lasts at least three or four years with some data showing effectiveness for five years. Following removal, fertility quickly returns.

Diana M. Zuckerman is an American health policy analyst who focuses on the implications of policies for public health and patients' health. She specializes in national health policy, particularly in women's health and the safety and effectiveness of medical products. She is the President of the National Center for Health Research and the Cancer Prevention and Treatment Fund.

The National Women's Health Network (NWHN) is a non-profit women's health advocacy organization located in Washington, D.C. It was founded in 1975 by Barbara Seaman, Alice Wolfson, Belita Cowan, Mary Howell, and Phyllis Chesler. The stated mission of the organization is to give women a greater voice within the healthcare system. The NWHN researches and lobbies federal agencies on such issues as AIDS, reproductive rights, breast cancer, older women's health, and new contraceptive technologies. The Women's Health Voice, the NWHN's health information program, provides independent research on a variety of women's health topics.

Sybil Niden Goldrich is a women’s health advocate, primarily concerning breast implants.

A contraceptive implant is an implantable medical device used for the purpose of birth control. The implant may depend on the timed release of hormones to hinder ovulation or sperm development, the ability of copper to act as a natural spermicide within the uterus, or it may work using a non-hormonal, physical blocking mechanism. As with other contraceptives, a contraceptive implant is designed to prevent pregnancy, but it does not protect against sexually transmitted infections.

Medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), also known as depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) in injectable form and sold under the brand name Depo-Provera among others, is a hormonal medication of the progestin type. It is used as a method of birth control and as a part of menopausal hormone therapy. It is also used to treat endometriosis, abnormal uterine bleeding, paraphilia, and certain types of cancer. The medication is available both alone and in combination with an estrogen. It is taken by mouth, used under the tongue, or by injection into a muscle or fat.

Sheldon Jerome Segal was an American embryologist and biochemist who spent his entire career working on contraception, and made major innovations in the field of long-lasting alternatives, with Chilean physician Horacio Croxatto, including in the creation of Norplant, the first major development advance in birth control since the birth control pill.

The birth control movement in the United States was a social reform campaign beginning in 1914 that aimed to increase the availability of contraception in the U.S. through education and legalization. The movement began in 1914 when a group of political radicals in New York City, led by Emma Goldman, Mary Dennett, and Margaret Sanger, became concerned about the hardships that childbirth and self-induced abortions brought to low-income women. Since contraception was considered to be obscene at the time, the activists targeted the Comstock laws, which prohibited distribution of any "obscene, lewd, and/or lascivious" materials through the mail. Hoping to provoke a favorable legal decision, Sanger deliberately broke the law by distributing The Woman Rebel, a newsletter containing a discussion of contraception. In 1916, Sanger opened the first birth control clinic in the United States, but the clinic was immediately shut down by police, and Sanger was sentenced to 30 days in jail.

Birth control in the United States is available in many forms. Some of the forms available at drugstores and some retail stores are male condoms, female condoms, sponges, spermicides, over-the-counter progestin-only contraceptive pills, and over-the-counter emergency contraception. Forms available at pharmacies with a doctor's prescription or at doctor's offices are oral contraceptive pills, patches, vaginal rings, diaphragms, shots/injections, cervical caps, implantable rods, and intrauterine devices (IUDs). Sterilization procedures, including tubal ligations and vasectomies, are also performed.

A contraceptive mandate is a government regulation or law that requires health insurers, or employers that provide their employees with health insurance, to cover some contraceptive costs in their health insurance plans.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Indian Health Service (IHS) and collaborating physicians sustained a practice of performing sterilizations on Native American women, in many cases without the free and informed consent of their patients. In some cases, women were misled into believing that the sterilization procedure was reversible. In other cases, sterilization was performed without the adequate understanding and consent of the patient, including cases in which the procedure was performed on minors as young as 11 years old. A compounding factor was the tendency of doctors to recommend sterilization to poor and minority women in cases where they would not have done so to a wealthier white patient. Other cases of abuse have been documented as well, including when health providers did not tell women they were going to be sterilized, or other forms of coercion including threatening to take away their welfare or healthcare.