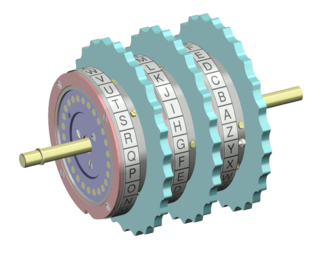

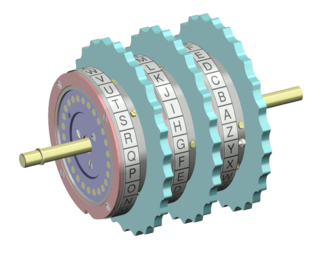

The Enigma machine is a cipher device developed and used in the early- to mid-20th century to protect commercial, diplomatic, and military communication. It was employed extensively by Nazi Germany during World War II, in all branches of the German military. The Enigma machine was considered so secure that it was used to encipher the most top-secret messages.

Ultra was the designation adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park. Ultra eventually became the standard designation among the western Allies for all such intelligence. The name arose because the intelligence obtained was considered more important than that designated by the highest British security classification then used and so was regarded as being Ultra Secret. Several other cryptonyms had been used for such intelligence.

In the history of cryptography, Typex machines were British cipher machines used from 1937. It was an adaptation of the commercial German Enigma with a number of enhancements that greatly increased its security. The cipher machine was used until the mid-1950s when other more modern military encryption systems came into use.

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of State for Air.

In cryptography, a rotor machine is an electro-mechanical stream cipher device used for encrypting and decrypting messages. Rotor machines were the cryptographic state-of-the-art for much of the 20th century; they were in widespread use from the 1920s to the 1970s. The most famous example is the German Enigma machine, the output of which was deciphered by the Allies during World War II, producing intelligence code-named Ultra.

A keypunch is a device for precisely punching holes into stiff paper cards at specific locations as determined by keys struck by a human operator. Other devices included here for that same function include the gang punch, the pantograph punch, and the stamp. The term was also used for similar machines used by humans to transcribe data onto punched tape media.

Cryptanalysis of the Enigma ciphering system enabled the western Allies in World War II to read substantial amounts of Morse-coded radio communications of the Axis powers that had been enciphered using Enigma machines. This yielded military intelligence which, along with that from other decrypted Axis radio and teleprinter transmissions, was given the codename Ultra.

Cryptography was used extensively during World War II because of the importance of radio communication and the ease of radio interception. The nations involved fielded a plethora of code and cipher systems, many of the latter using rotor machines. As a result, the theoretical and practical aspects of cryptanalysis, or codebreaking, were much advanced.

Peter Frank George Twinn was an English mathematician, Second World War codebreaker and entomologist. He was the first mathematician to be recruited to GC&CS, Head of Intelligence Service Knox (ISK) from 1943, the unit responsible for decrypting over 100,000 Abwehr communications.

In cryptography, Fialka (M-125) is the name of a Cold War-era Soviet cipher machine. A rotor machine, the device uses 10 rotors, each with 30 contacts along with mechanical pins to control stepping. It also makes use of a punched card mechanism. Fialka means "violet" in Russian. Information regarding the machine was quite scarce until c. 2005 because the device had been kept secret.

Frederick George Creed was a Canadian inventor, who spent most of his adult life in Britain. He worked in the field of telecommunications, and is particularly remembered as a key figure in the development of the teleprinter. He also played an early role in the development of SWATH vessels.

A cipher disk is an enciphering and deciphering tool developed in 1470 by the Italian architect and author Leon Battista Alberti. He constructed a device, consisting of two concentric circular plates mounted one on top of the other. The larger plate is called the "stationary" and the smaller one the "moveable" since the smaller one could move on top of the "stationary".

The B-Dienst, also called xB-Dienst, X-B-Dienst and χB-Dienst, was a Department of the German Naval Intelligence Service of the OKM that dealt with the interception and recording, decoding and analysis of the enemy. In particular, it focused on British radio communications before and during World War II. B-Dienst worked on cryptanalysis and deciphering (decrypting) of enemy and neutral states' message traffic and security control of Kriegsmarine key processes and machinery.

German code breaking in World War II achieved some notable successes cracking British naval ciphers until well into the fourth year of the war, using the extensive German radio intelligence operations during World War II. Cryptanalysis also suffered from a problem typical of the German armed forces of the time: numerous branches and institutions maintained their own cryptographic departments, working on their own without collaboration or sharing results or methods. This led to duplicated effort, a fragmentation of potential, and lower efficiency than might have been achieved. There was no central German cryptography agency comparable to Britain’s Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), based at Bletchley Park.

BATCO, short for Battle Code, is a hand-held, paper-based encryption system used at a low, front line level in the British Army. It was introduced along with the Clansman combat net radio in the early 1980s and was largely obsolete by 2010 due to the wide deployment of the secure Bowman radios. BATCO consists of a code, contained on a set of vocabulary cards, and cipher sheets for superencryption of the numeric code words. The cipher sheets, which are typically changed daily, also include an authentication table and a radio call sign protection system.

C. Lorenz AG (1880–1958) was a German electrical and electronics firm primarily located in Berlin. It innovated, developed, and marketed products for electric lighting, telegraphy, telephony, radar, and radio. It was acquired by ITT in 1930 and became part of the newly founded company Standard Elektrik Lorenz (SEL) Stuttgart in 1958, when it merged with Standard Elektrizitätsgesellschaft and several other smaller companies owned by ITT. In 1987, SEL merged with the French companies Compagnie Générale d'Electricité and Alcatel to form the new Alcatel SEL.

The Cipher Department of the High Command of the Wehrmacht was the Signal Intelligence Agency of the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces of the German Armed Forces before and during World War II. OKW/Chi, within the formal order of battle hierarchy OKW/WFsT/Ag WNV/Chi, dealt with the cryptanalysis and deciphering of enemy and neutral states' message traffic and security control of its own key processes and machinery, such as the rotor cipher ENIGMA machine. It was the successor to the former Chi bureau of the Reichswehr Ministry.

Wilhelm Tranow was a German cryptanalyst, who before and during World War II worked in the monitoring service of the German Navy and was responsible for breaking a number of encrypted radio communication systems, particularly the Naval Cypher, which was used by the British Admiralty for encrypting operational signals and the Naval Code for encrypting administrative signals. Tranow was considered one of the most important cryptanalysts of B-service. He was described as being experienced and energetic. Little was known about his personal life, when and where he was born, or where he died.

Ferdinand Voegele was a German philologist and linguistic cryptanalyst, before and during the time of World War II and who would eventually lead the cipher bureau of the Luftwaffe Signal Intelligence Service.

Morgan Cyprian McMahon O'Brien (1886–1968) was born in New Zealand to Irish parents, and was an engineer and inventor with numerous patents particularly in the area of high-street and bank security, alarm systems, and ciphers. He moved to England in 1925, and patented an advanced cipher typewriter in 1928 which has been referred to as "Britain's Enigma", and just before WW2 he patented the coding device known as the SYKO cipher device used throughout the war by the allied air forces, and to some extent by the allied navies too.